Fall 2012 - Vol. 7, No. 3

The Evidence for Acupuncture in Cancer Therapy

Corey Fogleman, M.D.

Associate Director, LGH Family & Community Medicine Residency Program

Physician Acupuncturist, Family & Maternity Medicine & Downtown Family Medicine Offices

ABSTRACT

Cancer and treatment for cancer can cause a variety of symptoms, not all of which are appropriately managed with medical therapy. Acupuncture is one alternative treatment with relatively few risks or side effects. When the risk of an intervention is very low, the potential benefit may possess more total value. Thus, even if acupuncture’s beneficial effects are partially or even substantially related to its placebo effect, a reliable benefit should not be dismissed. Acupuncture’s utility for those with cancer is discussed in this review article which pulls from the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews.

Acupuncture can be recommended with good strength of evidence for post-operative nausea, and—when needles are stimulated manually or with electricity—for vomiting induced by chemotherapy. Acupuncture may be beneficial for pain related to cancer, and may offer some benefit to those with symptoms of secondary depression. It may improve quality of sleep but cannot be considered first-line therapy for those with insomnia.

It is unlikely to help those with hot flashes related to cancer or the treatment of cancer, nor those with dyspnea related to cancer. While acupuncture may aid those trying to quit smoking, it is unlikely by itself to make a long-term difference.

Acupuncture’s effectiveness for those with xerostomia, peripheral neuropathy, or fatigue is not analyzed in the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, but other reports in the medical literature suggest some benefit and support further study and review in these areas. Faith in therapy may promote benefits, so if patients express an interest in having acupuncture for certain cancer-related symptoms, we may be doing them a service by fostering that faith. The 2007 Guidelines of the American College of Chest Physicians suggest considering acupuncture for those with lung cancer who experience nausea, pain, neuropathy, or xerostomia.

THE EVIDENCE FOR ACUPUNCTURE IN CANCER THERAPY

Introduction

Patients afflicted with cancer often have symptoms directly related to their disease as well as to the modalities used to treat them, be it surgery, radiation, or chemotherapy. These symptoms may include pain, insomnia, altered mood, nausea, hot flashes, or breathlessness, among others. Although medical therapies may provide substantial benefit, there is room for discussion of alternative and complementary techniques, since they might provide fewer side effects and improve the patient’s tolerance of their disease and its treatment.

Acupuncture is a modality that has been used for thousands of years and is attractive in great part because it has relatively few risks. The risks are generally equivalent to – or less than – those associated with having blood drawn or receiving an injection for immunization. Indeed, the needles used in acupuncture are considerably smaller—on the order of 30-36 gauge—and often cause no pain during insertion. Their size limits the risk to internal structures, and with solid needles the potential for infection is considered negligible. A review of twelve prospective trials in Japan, Sweden, Singapore, Germany and the United Kingdom involving more than a million patients found the risk of serious adverse side effects was 0.05 per 10,000 treatments.1

This article will not examine the reasons why acupuncture works from an Eastern perspective. Indeed, arguments to that effect may be destined to fail the scrutiny of a Western mindset, and are superfluous to the more practical question, “does it work?” Those practitioners who question whether acupuncture is anything other than an elaborate placebo may be heartened to know that studies suggest the more elaborate a placebo, the more useful it may prove.2 Thus, if sham acupuncture is also effective, it may not be the best control in clinical trials. Further, research by Kaptchuk suggests that patients who believe in their therapy are more likely to improve.3 Since most uses of acupuncture involve subjective symptoms whose intensity can only be judged by the patient, it stands to reason that the benefit of acupuncture could, at least in part, come from within. A better framing of the question then might be, “Is there sufficient evidence that patients should invest their confidence in acupuncture to treat cancer-related symptoms?”

Taking these issues into consideration, this article will review the investigations compiled in one of the most respected compendiums of medical research, the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, to elucidate whether it is appropriate to recommend acupuncture when counseling patients with cancer.

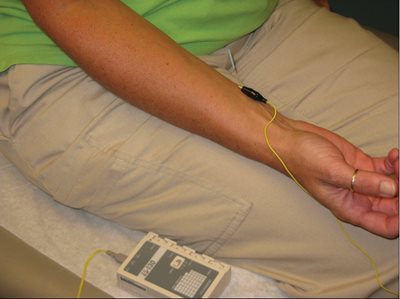

Pic 1 : Photo showing a patient with Serin type 36 Gauge Needle at point MH 6 (P6) on the right arm, a point commonly used for nausea, connected to an ES-130 Electroacupuncture Unit.

Pic 2: Photo showing a patient with Serin type 36 Gauge Needle at point MH 6 (P6) on the right arm, a point commonly used for nausea.

Pic 3: Photo showing a patient with Serin type 36 Gauge Needle at point ST 45 on the R ankle, a point commonly used for nausea, connected to an ES-130 Electroacupuncture Unit.

Acupuncture for Nausea

One of the most common symptoms in patients treated for cancer is nausea, whether related to their disease or to its treatments. Anti-emetics, including 5HT3 inhibitors and anti-cholinergics, are effective, but may be associated with side effects as well as significant cost. In a Cochrane Review updated in December 2010, 40 trials that contained a total of 4,858 patients compared the stimulation of point MH 6 on the wrist to sham acupuncture for the treatment of postoperative nausea and vomiting.4 Compared with sham therapy, acupuncture treatment at point MH6 reduced nausea (RR 0.71, 95% CI0.61-0.83), vomiting (RR 0.70, 95% CI 0.59-0.83), and the need for rescue anti-emetics (RR 0.69, 95% CI 0.57-0.83). Compared with anti-emetic treatment, there appeared to be no difference versus treatment at MH 6 for nausea, vomiting, or the need for rescue medicines. Pooled analysis concluded that acupuncture was effective if MH6 was needled in any of several ways—using no stimulation, with electrical stimulation, or using noninvasive electrical stimulation. Therefore, it seems prudent to offer treatment of MH6 to patients for prevention of nausea related to surgery.4

In a complementary Cochrane Review updated in February 2011, eleven trials involving a total of 1,247 patients analyzed acupuncture for treating nausea and vomiting related to chemotherapy.5 Overall, stimulation of the acupuncture points was effective. Specifically, stimulation of MH 6 using acupressure before undergoing chemotherapy provided statistically significant prevention of nausea (SMD = -0.19, 95% CI -0.37 to -0.01, P = 0.04) and a non-statistically significant prevention of vomiting (RR= 0.83, 95% CI 0.6 to 1.16) versus placebo. Acupuncture for this purpose may be used in a variety of ways including manual stimulation of one or both MH6 points, electro-acupuncture stimulation of MH6 alone, or a combination of electrical stimulation with points such as ST 45. Pooled analysis, however suggests that the use of any of these methods provides statistically significant benefit to those with acute vomiting due to chemotherapy compared with placebo or sham (RR =0.74, 95% CI 0.58-0.94 P=0.01, NNT = 4.4). Acupuncture seems no more effective than 5HT3 inhibitors, but is appropriate in those who cannot or should not use those medications.5

Acupuncture for Pain

Acupuncture is effective for acute and chronic musculoskeletal and migraine pain, as well as pain related to labor.6,7,8 Therefore, it seems reasonable to consider acupuncture for those with cancer-related pain. In a Cochrane Review of acupuncture for cancer pain published in January 2011, a total of three trials including 204 patients were examined.9 Each showed acupuncture to be beneficial, although results could not be pooled because of heterogeneity. A related analysis of pain treated by stimulating traditional acupuncture points using transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) without needles found no benefit versus placebo, suggesting that needling is necessary for effective management of pain .1

Auricular acupuncture, using either short term ear needling for at least 45 minutes or semi-permanent ear needles left in and allowed to fall out on their own (generally this can take up to seven days), was studied in a notably high quality manner.9 In a trial involving 90 patients, acupuncture improved pain scores at 1 and 2 month intervals after baseline by 36% on the visual analogue scale (VAS) compared with sham acupuncture which improved scores by merely 3% (p < 0.0001). It is recommended that if acupuncture is used in this manner, it should be performed at least once weekly and for up to six weeks.9

Acupuncture for Hot Flashes

Hot flashes are a common and troubling side effect in women who have been treated for breast and other cancers. Acupuncture was reviewed as part of a 2010 Cochrane analysis of a variety of non-hormonal modalities,10 but the reviewers found only one trial that compared acupuncture therapy with sham, and it showed no benefit in these patients (for 67 women, mean difference was -0.10, 95% CI -3.63 to 3.43). At this time there is no reason to recommend acupuncture for hot flashes related to treatment for cancer, and there is good evidence that medicines such as clonidine, SNRI’s, SSRI’s, gabapentin and relaxation therapy offer benefit.10

Acupuncture for Dyspnea

Dyspnea is a distressing symptom associated with a variety of disorders, including cancer. This is an especially important area of concern as the standard treatment options are benzodiazepines, with their high risk for side effects. A 2008 Cochrane Review looked at the literature for a variety of interventions to treat dyspnea associated with malignancy.11 There were five trials that examined acupuncture or acupressure, but only one involved cancer patients; the remaining studies focused on COPD. The one trial of acupuncture in patients with cancer showed no more improvement in outcome than treatment with sham acupuncture, but both arms of this study did show improvement in dyspnea. Of the four other trials, two showed that treatment significantly improved symptoms of dyspnea associated with COPD but the trial numbers were small and the study types too heterogeneous to undergo meta-analysis. Overall, the Cochrane authors concluded that evidence is inadequate to routinely recommend acupuncture for dyspnea associated with cancer. Nonpharmacologic interventions which seem to be effective based on this review include breathing training, walking aids, neuromuscular electrical stimulation and chest wall vibration therapy.11

Acupuncture for Secondary Depression and Insomnia

Patients with depressed mood and sleep problems associated with their diagnosis might be treated in a variety of nontraditional ways including acupuncture. A 2009 Cochrane meta analysis of acupuncture for treatment of depression pooled 30 trials and 2,812 patients.12 Eight of these trials showed benefit with acupuncture, but the variety of techniques used and the variety of comparisons—versus sham, versus no treatment, in addition to or versus SSRI—contributed to a high degree of heterogeneity and a sense of bias by the reviewers. Overall, the conclusion was that the risk of bias in the majority of trials means acupuncture cannot be recommended for depression alone.12

Interestingly, in a subgroup of patients with depression as a co-morbidity of stroke—consisting of 8 trials with a total of 935 patients—there was good evidence that acupuncture was effective in these patients. This was especially true regarding the comparison of manual acupuncture versus SSRI’s (RR 1.66, 95%CI 1.03 -2.68). These results may carry implications for those whose depression is coincident with other diagnoses, such as cancer. Based on this subgroup analysis, it seems reasonable to offer acupuncture to patients with new-onset secondary-depression.12

Insomnia secondary to other medical disorders must be addressed first by treating the underlying disorder. Otherwise, it can be a vexing problem to treat not least because its definition varies between patients, and can include difficulty with initiating sleep, frequent awakening, poor quality of sleep, or restlessness. In addition, medicines approved for treatment are by-and-large benzodiazepine receptor agonists which carry risk for abuse. Although insomnia can be a chronic problem, with rare exception medical treatments are only FDA approved for short term use. In a 2009 Cochrane analysis of acupuncture for treatment of insomnia, acupuncture seemed better than no treatment regarding its effect on sleep quality, and when added to the treatment of sleep hygiene or estazolam it consistently improved post-treatment quality-of-sleep scores.13 However, acupuncture in its various forms did not seem to reliably impact sleep latency or sleep duration and reviewers again noted such a high degree of heterogeneity and bias that acupuncture cannot be reliably recommended for use in all patients with insomnia.13

Acupuncture for Smoking Cessation

For smokers, particularly those with cancer, quitting is likely the most important change they can make for the benefit of their health. While there are several accepted forms of pharmacologic smoking-cessation aids available, the overall success rate is still only 1-2% yearly, so the addition of any technique to aid in smoking cessation would be beneficial.14 In a 2011 Cochrane analysis of acupuncture, acupressure, electrical and nonelectrical methods, the authors examined 33 reports and concluded that while acupuncture has a statistically significant benefit versus sham for short term cessation (RR 1.18,95% CI 1.03-1.34), there was overall too much heterogeneity and/or bias in the literature.14 Therefore, the authors concluded that acupuncture—in any of its various forms—cannot be recommended over nicotine replacement therapy.

Other areas that have been analyzed but for which there are no Cochrane Reviews

Acupuncture is reported to be beneficial for neuropathy, cancer related fatigue, and xerostomia. Of these only the latter has been examined in a systematic review,15 but meta-analysis was limited by heterogeneity and the authors concluded the evidence is too unconvincing to recommend acupuncture.

DISCUSSION

Overall, acupuncture can be recommended with good strength of evidence for post-operative nausea, and, when needles are stimulated manually or with electricity, for those with chemotherapy-induced vomiting. Acupuncture therapy may be beneficial for pain related to cancer, and may offer those with secondary depression symptoms some benefit. It may help with sleep quality but cannot be considered first-line for those with insomnia. It is unlikely to help those with hot flashes related to cancer or the treatment of cancer, nor those with cancer-related dyspnea. While acupuncture may aid those who are trying to quit smoking, it is unlikely by itself to make a long term difference in those attempting tobacco cessation. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews contains no analysis of acupuncture’s effectiveness for those with xerostomia, peripheral neuropathy or fatigue.

In 2007 the American College of Chest Physicians published guidelines addressing the use of complementary and alternative therapies. The guidelines encourage practitioners to discuss CAM with all lung cancer patients. Specifically, the guidelines encourage the use of acupuncture—backed up by level 1A or 1B evidence—in those lung cancer patients with nausea, pain, neuropathy and xerostomia.16

When discussing the role acupuncture may play in the treatment of cancer-related symptoms some key points to keep in mind include the following:

1. Treatment for multiple problems can be identical. That is, acupuncture treatment is not entirely analogous to most Western therapy, wherein one kind of therapy treats one kind of problem. Steroids treat inflammation, opioids treat pain, and antiemetics treat nausea. Acupuncture must be planned and made appropriate to the individual patient, but once the patient is appropriately interviewed, examined and the proper treatment algorithm is chosen, the same treatment algorithm may be employed for a variety of problems, including inflammatory, nociceptive and gastronomic issues.

2. Acupuncture has little risk and its overall cost is low compared with that of medicine. One treatment costs $50-100 and one course of treatment may entail one to twelve visits.

3. Acupuncture’s value is often judged against sham, but caution should be exercised when suggesting acupuncture has little value if sham is beneficial as well. For example, in the Cochrane analysis of acupuncture’s value for dyspnea, the authors conclude the quality of evidence was low, not because acupuncture didn’t improve outcomes but because the study suggests sham may have value as well. We can picture sham acupuncture delivered with adequate provider attention, in a clinical setting with otherwise appropriate clinical procedures and follow up. Evidence suggests that an elaborately performed and involved placebo has more effect than a placebo of the typical “sugar pill” variety.2 Thus, it may test our sense of logic but we should not disregard effective yet sham therapy.

4. Studies show that patients respond to those health interventions in which they have faith.3 So, if patients express interest in having acupuncture for problems such as pain, nausea, dyspnea, insomnia, depressed mood or xerostomia, we may be doing them a service by fostering that faith. Statements as innocuous as, “Acupuncture works for many patients like you for this problem,” are backed up by evidence from one of the most respected databases of systematic reviews.

5. There are a variety of acupuncture techniques to choose from, and they can be used in combination, such that there are virtually an unlimited number of potential treatment techniques for any given patient. Therefore, it is difficult to point to one technique in acupuncture and conclude that its ineffectiveness implies that all techniques are inadequate. Likewise, it is difficult to identify which technique in acupuncture is likely the one, above all others, that is ideal for a given patient. Acupuncture is a highly individualized therapy requiring prolonged close contact between provider and patient and there is great potential for varying the treatment plan; thus, it does not lend itself readily to randomized controlled evaluation. The caveat is that because treatment plans for each patient are likely to be designed with that particular patient in mind—that is, their acupuncturists “took their best shot”—we must assume that if the majority of patients say it does not work, then it does not.

Clinical Practice Guidelines were published in 2006 by the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) to guide the use of acupuncture in those with cancer.17 These guidelines include suggestions for defining the roles and responsibilities of the practitioner; establishing the criteria for acupuncture practice; considering which patients are appropriate candidates for acupuncture; determining which contraindications and cautions to consider; learning how to perform treatments, how to conduct clinic review and audit, and finally, how to advise patients who hope to accomplish self-needling. These guidelines suggest acupuncture be considered for each of the symptoms described in this article. Finally, they provide a framework for how to establish clinical practice when acupuncture is offered to those patients with other underlying diseases.

REFERENCES

1 Hurlow, Adam, Bennett, Michael I, Robb, Karen A, Johnson, Mark I, Simpson, Karen H, Oxberry, Stephen G. Transcutaneous electric nerve stimulation (TENS) for cancer pain in adults. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2012, Issue 3. Art. No.: CD006276. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD006276.pub3.

2 Crow, R, Gage H. Hampson, S, Hart, J, Kimber, A, Thomas, H. The role of expectancies in the placebo effect and their use in the delivery of health care: a systematic review. Health Technology Assessment 1999;3(3):1-96.

3 Kaptchuk, TJ, Stason, WB, Davis, RB, Legezda, ATR, Schnyer, RN, Kerr, CE, et al. Sham device v inert pill: randomised controlled trial of two placebo treatments. BMJ 2006;332(7538):391-7

4 Lee, Anna, Fan, Lawrence TY. Stimulation of the wrist acupuncture point P6 for preventing postoperative nausea and vomiting. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2009, Issue 2. Art. No.: CD003281. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD003281.pub3

5 Ezzo, Jeanette, Richardson, Mary Ann, Vickers, Andrew, Allen, Claire, Dibble, Suzanne, Issell, Brian F, Lao, Lixing, Pearl, Michael, Ramirez, Gilbert, Roscoe, Joseph A, Shen, Joannie, Shivnan, Jane C, Streitberger, Konrad, Treish, Imad, Zhang, Grant. Acupuncture-point stimulation for chemotherapy-induced nausea or vomiting. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2006, Issue 2. Art. No.: CD002285. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD002285.pub2

6 Trinh, Kien, Graham, Nadine, Gross, Anita, Goldsmith, Charles H, Wang, Ellen, Cameron, Ian D, Kay, Theresa M. Acupuncture for neck disorders. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2006, Issue 3. Art. No.: CD004870. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD004870.pub3.

7 Linde, Klaus, Allais, Gianni, Brinkhaus, Benno, Manheimer, Eric, Vickers, Andrew, White, Adrian R. Acupuncture for migraine prophylaxis. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2009, Issue 1. Art. No.: CD001218. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD001218.pub2.

8 Smith, Caroline A, Collins, Carmel T, Crowther, Caroline A, Levett, Kate M. Acupuncture or acupressure for pain management in labour. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2011, Issue 7. Art. No.: CD009232. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD009232.

9 Paley, Carole A, Johnson, Mark I, Tashani, Osama A, Bagnall, Anne-Marie. Acupuncture for cancer pain in adults. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2011, Issue 1. Art. No.: CD007753. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD007753.pub2

10 Rada, Gabriel, Capurro, Daniel, Pantoja, Tomas, Corbalán, Javiera, Moreno, Gladys, Letelier, Luz M, Vera, Claudio. Non-hormonal interventions for hot flushes in women with a history of breast cancer. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2010, Issue 9. Art. No.: CD004923. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD004923.pub2.

11 Bausewein, Claudia, Booth, Sara, Gysels, Marjolein, Higginson, Irene J. Non-pharmacological interventions for breathlessness in advanced stages of malignant and non-malignant diseases. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2008, Issue 2. Art. No.: CD005623. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD005623.pub2

12 Smith, Caroline A, Hay, Phillipa PJ, MacPherson, Hugh. Acupuncture for depression. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2010, Issue 1. Art. No.: CD004046. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD004046.pub3

13 Cheuk, Daniel KL, Yeung, Jerry, Chung, KF, Wong, Virginia. Acupuncture for insomnia. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2007, Issue 3. Art. No.: CD005472. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD005472.pub2

14 White, Adrian R, Rampes, Hagen, Liu, Jian Ping, Stead, Lindsay F, Campbell, John. Acupuncture and related interventions for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2011, Issue 1. Art. No.: CD000009. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD000009.pub3.

15 O'Sullivan EM, Higginson IJ. Clinical effectiveness and safety of acupuncture in the treatment of irradiation-induced xerostomia in patients with head and neck cancer: a systematic review. Acupuncture Medicine 2010 Dec; 28 (4) : 191-9

16 Cassileth BR, Deng GE, Gomez JE, Johnstone PA, Kumar N, Vickers AJ, American College of Chest Physicians. Complementary therapies and integrative oncology in lung cancer: ACCP evidence-based clinical practice guidelines (2nd edition). Chest 2007 Sep;132(3 Suppl):340S-54S.

17 Filshie J, Hester J. Guidelines for providing acupuncture treatment for cancer patients—a peer reviewed sample policy document. Acupunct Med. 2006 Dec;24(4):172-82.

Thank you to patient Kelly Aponte (Acc Pic 1-3)