Click to Print Adobe PDF

Click to Print Adobe PDF

Summer 2012 - Vol.7, No.2

|

A History of Ophthalmology in Lancaster County

Paul H. Ripple, M.D. and John H. Bowman, M.D.

Ophthalmalogists (retired)

|

|

OPTHALMOLOGY IN ANTIQUITY

Historical references to Ophthalmology go back to ancient Egypt, Babylonia, and India. The Egyptians were particularly advanced in the practice and art of treating eye disorders. In Babylonia, according to Herodotus the historian of ancient Greece, medicine was practiced by priests and surgery by skilled hand-workers or chirorgos, a Greek word that combines the words for hand and work to mean surgeon. They practiced couching for resolution of a cataract (depression of the cornea or even insertion of a sharp instrument to displace the lens into the vitreous, often with disruption of the lens capsule). Though this method was perhaps first developed by the surgeons of India in the early 15th century BC,1 Babylonian skilled hand workers were motivated to master couching by the Code of Hammurabi, which allowed a handsome payment for a successful operation with the uneventful removal of a cataract and restoration of vision. In contrast, the surgeon who had a bad outcome, such as blindness, could pay a horrific cost and have his hands cut off.2

Egyptian medicine was highly specialized, and there were those who confined their study and management to the diseases of the eye,3 using several ophthalmology treatments. This focus on the eye was illustrated by their use of the “Eye of Horus” as a symbolic weapon to ward off evil and restore health and harmony. The symbol depicts an eye and the cheek markings of a falcon, a bird with legendary vision. It persists to this day, having evolved into the symbol “Rx” to identify medical prescriptions,4 and as the source of the eye in the pyramid of the Great Seal of the United States, depicted on the back of the dollar bill.

Some believe that the Edwin Smith papyrus, which dates to about 1500 B.C., derives from the practices of Imhotep, an earlier Egyptian physician who lived around 2500 BC. If true, this suggests that Egyptian surgery and medicine, including ophthalmology, were highly advanced at a very early date.5 Their doctors apparently knew about and treated such conditions as night blindness, distortions of the eyelids (blepharitis, , trichiasis, ectropion, entriopion), infections and inflammations, (chemosis, iritis, trachoma, chalazion, granulations, leucoma, staphyloma, and dacrocystitis), pterygium, hyphaema, ophthalmoplegia, and of course cataracts.6

THE CLASSICAL PERIOD AND THE MIDDLE AGES

Through the subsequent millennia of the Greek and Arabian Periods, even though there was a better understanding of the anatomy and pathology of the eye, and that opthalmia could be contagious, there were no great advances in the treatment or management of eye disorders. This is not to disparage the contributions of Galen, Vesalius and others, but they did not lead to practical clinical benefits until the ophthalmoscope was developed by Helmholtz in 1850.7 That invention resulted in revolutionary advances in the diagnosis and treatment of ophthalmological disorders such as glaucoma, infections, and inflammatory eye diseases.

The use of spectacles evolved as a separate science. Magnifying glasses were used during antiquity, but a better understanding of the eye’s physiology and its optics led to gradual improvements in the use of visual aids. Still, glasses with concave lenses were probably not introduced until the late 13th century.8

THE ROOTS OF THE MODERN ERA

Fig. 1: Wig Spectacles such as these became a fashion statement during the 1700s. The loops at the ends were designed to hook into a man's wig.

Spectacles were not introduced until the 16th century, and came into general use in the 18th, at which time Benjamin Franklin invented bifocals.9 At first, advances in America derived from work done by the early investigators in Europe, especially beginning in the mid-19th century. Unfortunately, quackery played a detrimental role in the management of eye disorders throughout the colonial period. The exemplar of exploitative quack practitioners in England was “Chevalier” John Taylor, a notorious self-promoter who claimed to have treated “eyes of all the British nobility,” including George II who had appointed him as his personal oculist.10 In fact, Taylor probably blinded hundreds, if not thousands of subjects. Like all these charlatans, he was principally an itinerant practitioner who – much like a snake oil salesman – relied on his own oratorical skills, powers of persuasion, and the slow avenues of communication in existence then to keep ahead of reports of his bad outcomes.

With the introduction of the ophthalmoscope a growing number of physicians developed a special interest in eye disorders. Much of the initial history of ophthalmology is tied to expertise in cataract surgery, but with a better understanding of anatomy, physiology, and pathology of the eye, treatments became more sophisticated.11

OPHTHALMOLOGY IN LANCASTER COUNTY

Fig. 2. A 1915 example of an ophthalmoscope in the historical collection of the Lancaster City and County Medical Society

During the colonial period most generalist physicians treated simple eye diseases like infections, and some even did eye surgery; Lancaster County was no exception. The best source available in the early treatment of eye diseases here is from a series of lectures by a very intelligent and ambitious physician named George Barrett Kerfoot. He was a first generation Irishman, who served an apprenticeship with the famous Dr. Samuel Humes before going off to Jefferson Medical College to complete his medical studies in 1828. He gave public lectures on science, anatomy and physiology at the Lancaster Lyceum, and opened the Anatomical Hall on South Queen Street in 1833 to give public demonstrations on human anatomy, eye disease and surgery. These are fortunately accessible in the archives of LancasterHistory.org.12

Most of the named diseases and treatments from his lectures are difficult to fit into the current classification of diagnoses; nonetheless, the following disorders represent some of the diagnoses he used and his recommended treatments:

Inflammation of the ball of the eye. Treated with the use of debility tonics, mercury, opiates and warm applications of Dover, divers, as well as various medicinal powders.

Scrofulous eye disease (abscess, ulcerations, blisters). The treatment consisted of emetics, vinegar and water, cold compresses, bleeding and leeches.

Gonorrhea of the eye. The treatment involved lunar caustic (silver nitrate), Cambulls hair pumice, sulphur, caphron.

Selective ophthalmia. Treatments included bleeding and warm applications of a solution of lunar caustic (silver nitrate).

Styes. Treatment involved warm applications of Lunar caustics.

Dropsy of the eye. Treatment included calomel, digitalis squills (an herb), leeches, and blisters

Trachoma. Treatment involved the tapping of the eye.

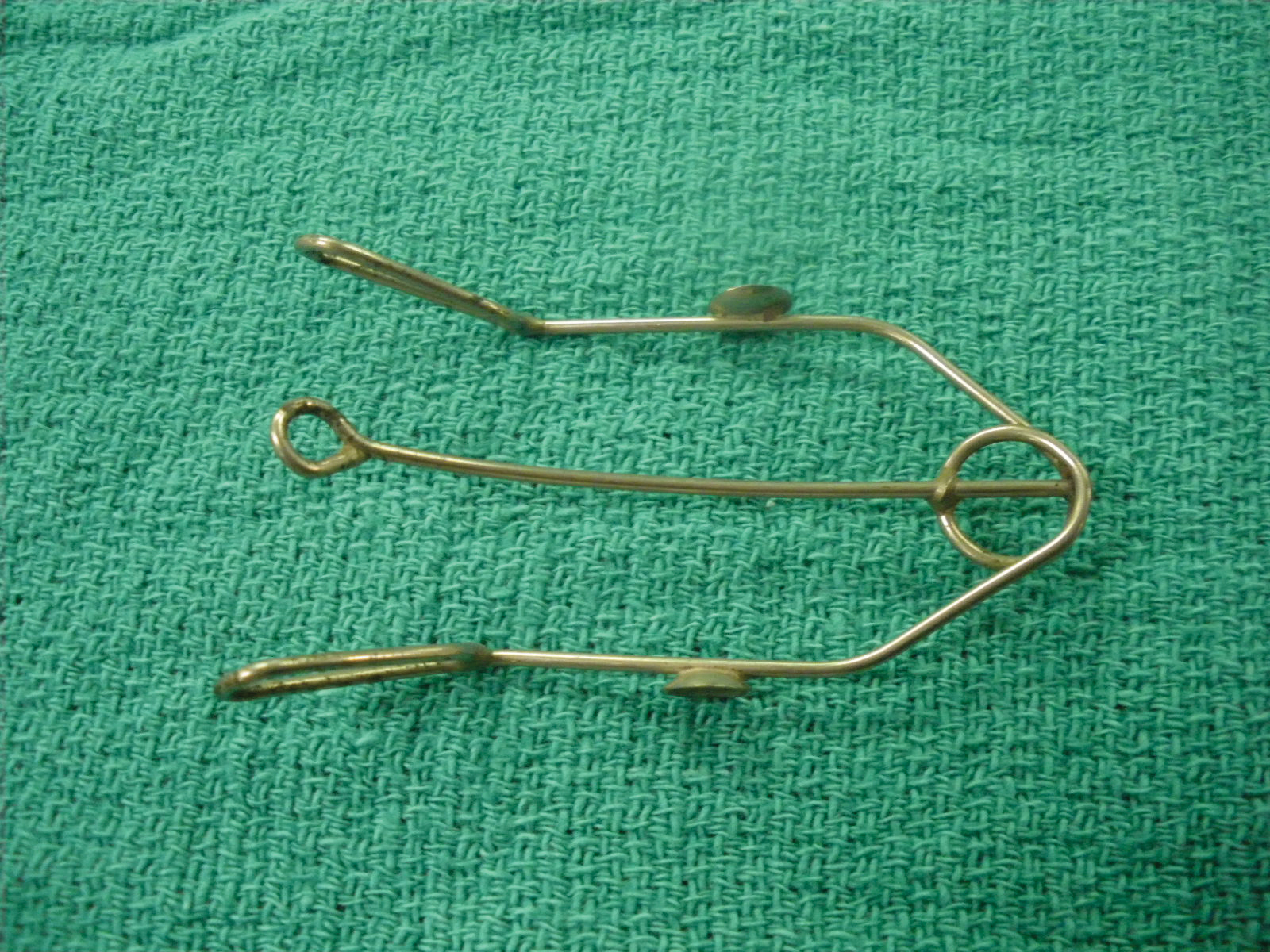

Fig. 3. This eyelid retractor was common in the 1880's for the use of everything from eye exams to simple surgeries.

Amaurosis (loss of vision). Not curable.

Pterygium. Treatment involved surgical removal.

Fistula Lachramalis. The treatment was the use of a probe to force tears into the nose.

Cataract. As noted above, couching had been used since antiquity. Dr. Duval of Paris advocated cataract extraction about 1700, and it replaced couching by the early nineteenth century. By 1868, Von Graefe’s “linear method” involved passing the cataract knife across the eye behind the cornea, pushing the cataract out of the eye while covering the cut with a conjunctional flap. He recommended that if the iris came out, it should not be pushed back in the eye, but removed by sticks of lunar caustic (silver nitrate). He cautioned that if the vitreous is lost the operation may not be successful.13

Fig. 4. A 1920s example of a tonometer in the historical collection of the Lancaster City and County Medical Society, used to check eye pressure for glaucoma.

Interestingly, there is no reference to glaucoma in Dr. Kerfoot’s diagnostic list, although it was, and still is, one of the most common eye diseases.

OPHTHALMOLOGY AT LANCASTER GENERAL HOSPITAL

At the Lancaster General Hospital, Dr. George B. Rohrer in 1902 and Dr. Walter B. Weidler in 1903 both practiced as oculists. In 1924 Dr. J. P. Roebuck is listed as an ophthalmologist and Chief of the Eye Department at The Lancaster General Hospital.

Through the latter part of the 19th century and throughout most of the first half of the 20th century, physicians who were trained in the treatment of eye disorders were also trained to treat conditions of the ear, nose, and throat.7 By 1909 a separate eye, ear, nose and throat operating room had been established in the hospital on North Lime Street. Dr. E. J. Stein who practiced eye and was also chief of the ENT department was followed by Dr. W. Hess Lefevre who in 1935 was chief of ENT and in 1940 was appointed Chief of the Eye Department at the General Hospital. Dr. T. C. Shookers, who also practiced both specialties, continued as chief of ENT after 1946. The last physicians trained in both eye and ENT who practiced in Lancaster were Dr. Roy Deck who opened his practice in 1920, followed by Dr. John Welch, Dr. Lloyd Hutchinson, and Dr. Joseph Medwick.

In 1916 physicians with proven expertise in ophthalmology established the first such specialty board in America to certify their competence in this specialized field of medicine and surgery.14 Many of the above physicians as well as some of the generalists with a special interest in eye disorders performed a limited degree of ocular surgery until the arrival in 1930 of Dr. Harry Fulton, Lancaster’s first full time board certified ophthalmologist. Dr. Fulton lived to be one of the oldest board certified ophthalmologists in America when he died in 1989 at age 103, having managed to do so despite smoking one pack a day until age 92. He only gave up smoking because he could no longer hold his cigarette. Dr. Fulton recruited another very well-trained, board certified ophthalmologist, Dr. Jerry Smith, but they broke up after 10 years. Both Dr. Smith and Dr. Fulton practiced on Duke Street just across from each other. Dr. Fulton later recruited another young associate, Dr. Dale Posey, who unfortunately developed Parkinson’s Disease and had to retire.

Refraction for glasses was a relatively easy task and quite lucrative, and many physicians included this service in their practices. Most generalists treated and still do treat many of the common ailments related to the eye. However, there were also non-board certified physicians with a specialized interest in ophthalmology that maintained an exclusive ophthalmology practice.

Dr. Paul Ripple finished his eye training at the School of Aviation Medicine and Washington University in 1953. He then returned to his hometown, Lancaster, and while waiting to open a new office he took over Dr. Smith’s practice for 3 months in order to give Dr. Smith an opportunity to take his first vacation since he left Dr. Fulton ten years before. One month after he returned from his vacation Dr. Smith had a heart attack and died. He, like Fulton, had been a heavy cigarette smoker. His practice was taken over by Dr. William Wheatley, a graduate of Wills Eye Hospital.

Dr. Zane Brown was the next board certified ophthalmologist in Lancaster and was quickly followed by Dr. John Bowman. The following physicians thereafter joined in various group practices: Drs. Robert White, William Spitler, Justin Cappiello, Cathy Rommel, Donald Thome, Barton Halpern, Harold Housman, William Reich, Joe Calkins, Daniel Pallen, John Sharp, Kerry Givens, Patrick Tiedeken, Jeffrey Choby, Pierre Palandjian, Lee Klombers, Theodore Jones, David Silbert, Donna Leonardo, Michael Pavlica, Diane Corallo, Persila Mertz, Thomas Krulewski, Francis Manning, Sanford Fritsch, and Julian Procope.

The first retinal specialist was Dr. Kenneth Messner, who came from Hershey Medical Center, followed by Dr. Roy Brod.

Major advances have been dramatic. A fascinating development was the sudden increase in blindness among premature babies after the introduction of new incubators that provided higher concentrations of oxygen. From its initial description in 1941, retinopathy of prematurity (ROP), which was then known as retrolental fibroplasia (RLF), became increasingly common in major teaching hospitals in affluent, developed countries where these incubators were in frequent use. Institutions such as Lancaster General Hospital had few such problems because they continued to use the old incubators. It wasn’t until a decade later that a controlled study in 1951 established the link between oxygen concentration and RLF, oxygen levels in incubators were lowered, and the epidemic was halted.

The numerous great advances in ophthalmology have occurred mostly during the current generation of ophthalmologists. Developments in the management of RLF and cataracts in the great eye centers such as the Scheie Eye Institute of the University of Pennsylvania and the Wills Eye Hospital at Jefferson have been steadily disseminated to community hospitals. Advances in cataract surgery such as finer surgical sutures, better needles, phako-emulsification, and smaller incisions, have greatly reduced postoperative complications, so that cataract extraction is now an outpatient procedure. With the development of the intra-ocular lens implant by Dr. Ridley in London, cataract surgery has reached a new era. Moreover, refractive surgery developed by Dr. Svyatoslav Fyodorov in Russia in the 1970s, first by radical keratotomy,15 and then by Dr. Ioannis Pallikaris in 1992 and others with Lasik (Laser Assisted In-Situ Keratomileusis), has enabled a cure for myopia.16 Glaucoma is no longer a disorder that inevitably leads to blindness, thanks to better drugs and laser surgery. Detached retinas are much better treated today with advances in diagnosis and laser surgery. We are now left with macular degeneration as the chief cause of visual loss in older people, but progress is evident with new preventive measures and laser approaches. Among the great technical advances is the operating microscope that makes eye surgery more exacting. Corneal diseases are getting better results with new corneal implants. Developments in low vision aids are also helping some persons.

There are still congenital eye diseases like retinitis pigmentosa that can lead to blindness, but a great deal of research is taking place and some progress is being made.

With help from Lancaster’s Blind Association a free eye clinic staffed by local specialists was established. It is considered one of the finest such eye services in the state for the medically indigent who are unable to pay.

One little story must end this article. Dr. Ripple had a patient who was very much in need of cataract surgery. The patient told Dr. Ripple that a powwow in Quarryville told him that he could treat his cataract. Dr. Ripple tried to convince him otherwise about this quack’s claim, but one day the patient came in and said he could see a lot better. He told Dr. Ripple the powwow put some powder in his eyes causing great pain. The powwow then couched his cataracts, utilizing this old method. The cataracts were still visible as they were displaced behind the pupil, but he now had good vision. Dr. Ripple gave him a prescription for glasses with cataract lenses if he promised to return for more definitive treatment to avoid an anticipated glaucoma or a detached retina. He never returned.

*Powwow or Hex Doctor is a Pennsylvania Dutch healer who uses religious charms to heal the sick by removing evil influences . Their theology was brought over from Germany in the late 17th and early 18th century, and continued into the 20th century. In essence the doctor feels he is a mediator between God and the patient.

REFERENCES

1.Porter, Roy, Cambridge Illustrated History of Medicine, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, England, 1996, p. 203

2.Porter, Roy, The Greatest Benefit to Mankind, A Medical History of Humanity, W.W. Norton & Company, New York, 1997, p. 48

3.Porter, Roy, The Greatest Benefit to Mankind, A Medical History of Humanity, W.W. Norton & Company, New York, 1997, p. 49

4.Sebastian, Anton, A Dictionary of the History of Medicine, The Parthenon Publishing Company, , New York, p. 401

5.Sebastian, Anton, A Dictionary of the History of Medicine, The Parthenon Publishing Company, , New York, p. 565

6.Lyons, Albert S., M.D, and Pettrucelli, R. Joseph, II, M.D. Medicine, An Illustrated History, Harry N. Abrams, Inc, Publishers, New York, 1978, p. 92

7.Lyons, Albert S., M.D, and Pettrucelli, R. Joseph, II, M.D. Medicine, An Illustrated History, Harry N. Abrams, Inc, Publishers, New York, 1978, p. 521

8.Porter, Roy, The Greatest Benefit to Mankind, A Medical History of Humanity, W.W. Norton & Company, New York, 1997, p. 116

9.Porter, Roy, The Greatest Benefit to Mankind, A Medical History of Humanity, W.W. Norton & Company, New York, 1997, p. 168

10.Porter, Roy, Cambridge Illustrated History of Medicine, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, England, 1996, p. 206

11.Lyons, Albert S., M.D, and Pettrucelli, R. Joseph, II, M.D. Medicine, An Illustrated History, Harry N. Abrams, Inc, Publishers, New York, 1978, p. 489

12.Dr. George B. Kerfoot Collection, 1828-1839, Archives, Lancasterhistory.org, Lancaster, PA

13.Sebastian, Anton, A Dictionary of the History of Medicine, The Parthenon Publishing Company, , New York, p. 356

14.Duffy, John, The Healers, A History of American Medicine, University of Illinois Press, Chicago, 1976, p. 295

15.Fyodorov, SN, and Dumev, VV. The use of anterior keratotomy method with the purpose of surgical correction of myopia, Practical Problems in Ophthalmic Surgery, Al Ivashina, Editor, Minister of Healthy, USSR, Moscow, pp. 47-48, 1977

16.Pallikaris, Ioannis, G, and Papadaki, Thekla, History of LASIK, Marcel Dekker, New York, 2003, pp.21-38