Click to Print Adobe PDF

Click to Print Adobe PDF

Summer 2009 - Vol.4, No.2

IMPROVING OUTCOMES FOR THE PATIENT WITH CLEFT LIP AND PALATE:

THE TEAM CONCEPT AND 70 YEARS OF EXPERIENCE IN CLEFT CARE

Ross E Long, Jr., DMD, MS, PhD

Director, Lancaster Cleft Palate Clinic

|

|

Background – The Importance of the Team Approach

In many parts of the world, the treatment of patients with clefts of the lip and palate has improved dramatically over the past decades. Normal speech, facial appearance, and dental occlusion are now goals that are expected and achievable in many cases. A wide range of successful treatment modalities has been developed in all areas of concern, providing the caregiver with a tremendous arsenal of tools from which to choose. Nonetheless, this wide range of treatment options also carries with it the expected controversies over the comparative efficacy and effectiveness of the various approaches.

Nonetheless, one approach to treatment has met with universal agreement - namely the need for these patients to be managed by an interdisciplinary team of specialists. Given the unique nature of this congenital problem, which affects structures involved in a number of different functions, it is only logical to expect that care-providers from multiple disciplines must be involved for total treatment of the patient. However, as summarized by Day[1] it is important to make a distinction between a multidisciplinary team and an interdisciplinary team:

"A multidisciplinary approach can occur as a series of isolated evaluations by several disciplines and does not imply the merger of evaluative insights of the shared development of a treatment plan, [which are the] hallmarks of a functional interdisciplinary team.[1]"

This emphasis on team treatment reached its maximum expression in the recently completed document "Parameters of Care" by the American Cleft Palate-Craniofacial Association under a grant from the Maternal and Child Care Bureau, Health Resources and Services Administration of the United States (1993).[2] A few of the fundamental principles expressed in this document emphasize the overriding importance of team treatment as the foundation for care of patients with clefts and craniofacial anomalies.

- Management of patients with craniofacial anomalies is best provided by an interdisciplinary team of specialists.

- Optimal care for patients with craniofacial anomalies is provided by teams that see sufficient numbers of patients each year to maintain clinical expertise in diagnosis and treatment.

- Treatment plans should be developed and implemented on the basis of team recommendations.

Lancaster Origins of the Team Approach

From an historical point of view, this understanding of the value of, and need for the team approach to cleft palate patient care, was not an accepted principle as recently as 70 years ago in the United States. It took the insight, vision, and energy of one orthodontist, working in Lancaster County, to recognize the difficulties inherent in the treatment of these patients and the need to integrate the services of many different specialists into this total treatment concept.

In the 1920's Dr. Herbert K. Cooper, a recent graduate of the University of Pennsylvania Dental School, completed his training in orthodontics at the Dewey School in New York City. He then returned to his hometown of Lititz, and opened his orthodontic practice. At the time, he was one of the few "dental specialists" in the center of Pennsylvania between Philadelphia and Pittsburgh. As a result, many patients with congenital oro-facial anomalies were referred to him, since there was no one else with "advanced" dental training to take care of these difficult problems. Many of these patients were older individuals who had become "dental cripples" as the result of poor early surgical management.

The enormous rehabilitative effort required to restore these patients to a level of near-normalcy led Dr. Cooper to realize that successful treatment could only be achieved through the coordinated efforts of many medical, dental, and speech specialists. His appointment as the dental consultant to nearby Elizabethtown Crippled Children's Hospital exposed him to the benefits of team treatment when dealing with patients who were handicapped by medical orthopedic problems. He also came to realize that the "facially crippled" patients with clefts seen in his private practice did not fit the definition of "crippled children" according to the criteria accepted by the medical community at that time, and none were able to be seen at the Crippled Children's Hospital. He lamented this inequity in a subsequent publication:

"We assume it is the intention of the State that every crippled child should be made self-supporting and whole. If he is lame, he is made to walk so he can go out in the world and become a useful, self-supporting citizen. But how singular it is that a child who has a facial deformity, either with or without a speech defect, according to the standards now established is relatively so unimportant - yet we try to prepare one child to walk up to ask for a job, while the other, who can walk there but cannot ask for it when he gets there, is neglected."[3]"

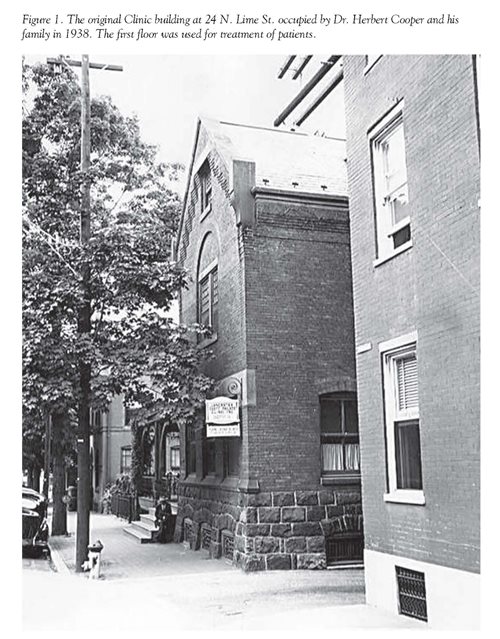

As a result of these conditions, he applied the same principles of team treatment used in the Crippled Children's Hospital to the treatment of patients with oro-facial anomalies. In 1938, despite the lingering Great Depression, Dr. Cooper moved his practice and family to 24 North Lime Street in downtown Lancaster and organized the first team in the world that was solely dedicated to the treatment of patients with these conditions. [Figure 1]. In the original house occupied by Dr. Cooper and his family, the first floor was converted to a number of dental operatories, as well as rooms for speech and hearing therapy, and others for medical examination.

The Contemporary Team Approach

Dr. Cooper's original team, which consisted of an orthodontist, a surgeon, and a "speech correctionist" (now speech pathologist), still stands as the foundation upon which cleft and craniofacial teams are built. The recent announcement by the CDC that cleft lip and palate is now the most common major birth defect in the U.S., occurring in one of every 575 live births, coupled with the understanding that clefting is just one manifestation of an entire spectrum of congenital craniofacial anomalies and syndromes, has promoted the expansion of Dr. Cooper's original idea of a multidisciplinary/interdisciplinary medical, dental and speech team to include, when needed, an even wider range of additional specialties. These include, among others, anesthesiology, audiology, genetics, neurology, neurosurgery, nursing, nutritionist/feeding specialty, ophthalmology, oral and maxillofacial surgery, orthodontics, otolaryngology, pediatrics, pediatric dentistry, plastic surgery, prosthodontics, psychology, radiology, social services and speech pathology.

With the multiple specialists required for complete rehabilitation, and the many procedures required, the average treatment costs per patient over their lifetime has been estimated by NIH at $250,000. With reimbursement rates from insurers and other sources often covering less than half of that, and the frequent exclusion by insurers, of non-surgical care which is required (dental, speech, psycho-social, etc), families are left with enormous out of pocket expenses, or must chose to deny their children much needed care. However, from the time of its creation, the Lancaster Cleft Palate Clinic has been committed to providing all care regardless of a family's ability to pay. Through the generosity of contributors, and charitable organizations, some support from the State Legislature and Department of Health, local support from LG, and most importantly the donation of time and expertise by our team surgeons from Hershey Medical Center and Harrisburg Hospital, and other team specialists from their private practices, the LCPC has been able to provide the standard of care for over 70 years in the face of persistent structural deficits. It truly represents a collaborative effort from many sources willing to put patient care above all else.

This "team effort" allows the LCPC to provide care for approximately 2,500 patients of all ages with facial birth defects. LCPC is one of only three primary full-service centers in Pennsylvania, the others being at the Children's Hospitals of Pittsburgh (CHP) and Philadelphia (CHOP). Because of the location of the other centers this means that the LCPC is responsible for nearly all cleft care in the entire central Pennsylvania region.

Of additional historical importance is that due to the unique nature of Lancaster Cleft Palate Clinic, in the 1940's, 1950's and 1960's, patients often traveled from all over the world in order to be seen at the Clinic. Those with extensive rehabilitation needs often stayed in Lancaster for 6-12 months in the Clinic's Residency Program so that as many of their surgical, speech, and dental needs could be managed as possible.

Today, the original team concept as applied to patients with oro-facial anomalies and developed at Lancaster[1][3][4][5] has become the standard of care and as stated above, is one of the few treatment parameters that has met with universal acceptance and approval in this complex, multidisciplinary field. As an example of the benefits of interdisciplinary team care is the improvement that has taken place in the area of post-surgical facial growth results. Dr. Cooper identified that many of the severe problems he handled in his early years, were the product of poor primary surgery carried out by surgeons "who had little experience with the structures of the mouth." As a result of extensive scar tissue left in growing areas of the maxilla, the significant maxillary growth deficiencies produced severe dento-facial deformities.

Prior to the early 1940's when the cleft palate team concept was in its infancy, not only were many surgeons poorly trained or inexperienced with cleft repairs, but also few had any dialogue with orthodontists concerning the growth principles of the face. With the inevitable interaction that took place between surgeons and orthodontists on newly formed teams, however, the long term growth consequences of injudicious primary surgery become apparent, leading ultimately to improvements in surgical skills and techniques with concomitant improvements in maxillary growth and dental occlusions. This is an example of the benefits of interactive team treatment whereby various specialists on the team are able to advise their colleagues on the team about the impact of their treatment procedures on other aspects of the rehabilitation process.

Of course another benefit of the team treatment process is the prospective interaction that occurs at face-to-face meetings of the team, as team members share with one another their plans for treatment in their individual specialty areas. This enables a coordination and integration of individual plans to insure that all treatment goals can be achieved without interfering with one another, as well as to avoid duplication of efforts to reduce the total burden of care imposed on the family and patient.

There are currently many variations in the manner in which teams actually function, ranging from those in which a single individual serves as the team leader throughout the course of treatment, through other team approaches where the leadership role rotates between the specialists on the team, depending on the age of the patient and the problems of greatest concern at any particular age. For instance, the surgeon's interests clearly predominate in infancy at the time of essential primary repairs; speech consideration may become overriding concerns in the child's pre-school years; and the orthodontist's objectives in the mixed dentition may assume a primary role in the decision-making process. At the Lancaster Cleft Palate Clinic, this "rotating" team leadership approach has been found to most effective, based on the levels of interest and the dynamics and chemistry between the various team members. As stated by Dr. Cooper:[5]

"We do not advocate a team without a leader, but we have found that major responsibilities for decisions may logically shift from one member to another or to two or three together as different problems are met at different stages in the patient's continuing program of treatment and rehabilitation."

However, it is also possible, in different situations, that a single dedicated, trained and experienced individual from a particular specialty may play the dominant role in directing team decisions through all stages of treatment. This may be especially true if the other team members are helpful but less experienced care-providers without a primary dedicated interest in overall management of patients with clefts.

The Lancaster Cleft Palate Clinic Today

In the management of cleft lip and palate and facial birth defects, uncoordinated procedures carried out by individual specialists with limited experience and no communication with the others involved in treating the patient, have the same consequences regardless of time or place. These include facial deformity, speech impairment, dental malformation, and psycho-social dysfunction. However, a review of the history and evolution of the successful treatment concepts learned through the experiences of ourselves and others can provide care-providers facing similar problems with an instant "road-map" for instituting the steps necessary to resolve these problems. Due to the international reputation of the LCPC, it has become an educational resource for professionals in all fields from around the world. Between 1950-1970, with few other such centers in operation, the LCPC held annual week-long NIH-sponsored educational symposia for professionals from all disciplines interested learning more about cleft lip and palate care. More recently LCPC has continued to provide learning opportunities for visitors from around the world, to share with them our experiences and current procedures for team care.

In the area of research, the LCPC has been the recipient of 3 major NIH grants over the years, the first of which led to the creation of the world's single largest repository of cleft lip and palate longitudinal treatment records. The outcomes were documented in areas of growth and development, dental occlusion, facial esthetics, speech and language development, audiological concerns and psycho-social development. Currently the LCPC is also engaged in a five-center NIH-funded study investigating Quality of Life in children with clefts, especially related to their secondary surgical procedures. Finally LCPC is now the organizing center for "Americleft", a North American intercenter collaborative treatment outcome study focused on determining "best practices" in cleft care, by comparing results between centers using widely different treatment approaches for primary surgical repairs.

Finally, as a result of this decades-old commitment to treatment, education and research, the LCPC's staff over the years has published several books or book chapters and has published more than 200 papers in scientific journals, thus sharing our experiences and findings with our colleagues. Opportunities to speak and invitations for key note addresses to further share the LCPC's history, philosophies, data, procedures and current research efforts continue today, with major presentations over the past several years to the Japanese Cleft Palate Association, the Craniofacial Society of Great Britain and Ireland, 8th European Craniofacial Congress, the Australian Society of Orthodontist, the 10th International Congress on Cleft Lip and Palate and Related Craniofacial Anomalies, the Centers for Disease Control Conference on Research for Orofacial Clefts, and the World Health Organization's Conference on Addressing the Global Challenges and Development of Registries for Clefts and Craniofacial Anomalies.

References

[1] Day DW. Perspectives on care: The interdisciplinary team approach. Otolyrngol Clin North Am 198; 14:769.

[2] American Cleft Palate-Craniofacial Association. Parameters for evaluation and treatment of patients with cleft lip/palate and other craniofacial anomalies. Chapel Hill, NC: American Cleft Palate-Craniofacial Assn. 1993.

[3] Cooper HK. Crippled children? Am J Ortho and Oral Surg 1942;28:35

[4] Cooper HK. Integration of services in the treatment of cleft lip and palate. J Am Dent Assoc 1953; 47:27

[5] Cooper HK. Historical perspectives and philosophy of treatment. In: Cooper HK, Harding RL, Krogman WM, Mazaheri M, Millard RT, Eds. Cleft Palate and Cleft Lip: A Team Approach to Clinical Management and Rehabilitation of the Patient. Philadelphia: WB Saunders, Co, 1979; 2.

Legends

[Figure1] The original Clinic building at 24 N. Lime St. occupied by Dr. Herbert Cooper and his family in 1938. The first floor was used for treatment of patients.

Ross E. Long, (Jr.) D.M.D, M.S., Ph.D.

Director, Lancaster Cleft Palate Clinic

223 North Lime Street

Lancaster, PA 17602

717-394-3793

relong@LGHealth.org