Winter 2024 - Vol. 19, No. 4

SCIENTIFIC REPORT

Anti-Obesity Pharmacotherapy Review

Clark Patterson

Meredith N. Clark, PharmD

Michelle Link Patterson, PharmD, BCACP

Ambulatory Pharmacist Clinicians

Penn Medicine Lancaster General Health

Obesity is a complex chronic condition with a steady increase in prevalence in the United States from 30.5% to 41.9% since the year 2000.

1 Obesity is linked to many complications including cardiovascular disease, stroke, diabetes, and certain cancers, which can, in turn, increase the estimated cost and burden of disease. Treatment of obesity means understanding the chronic nature of the condition and that there is a natural tendency to regain weight.

2 This is due to hormonal changes that occur following weight loss and adaptation of metabolism while in a calorie deficit.

2 As such, the presence of excess weight and obesity and prevention of weight gain should be considered in treatment decisions and prior to medication initiation.

Many medication classes are associated with weight gain or metabolic risks, including certain anticonvulsants (e.g., valproic acid, carbamazepine, gabapentin, pregabalin), antipsychotics (e.g., clozapine, olanzapine, quetiapine, risperidone), antidepressants (e.g., mirtazapine, tricyclic antidepressants), antihyperglycemic agents (e.g., insulin, sulfonylureas, thiazolidinediones), hormones, antihistamines, and glucocorticoids.

3 Although full discussion of the metabolic adverse effects of medications is outside the scope of this review, it is important to consider lower-risk medications when possible. For example, consider utilizing lower metabolic risk antipsychotics such as aripiprazole, lurasidone, and ziprasidone or utilizing agents that promote weight loss in type 2 diabetes such as metformin, glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonists, and GLP-1/glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide (GIP) dual receptor agonists when appropriate.

4,5

Lifestyle interventions, including calorie deficit and physical activity, are recommended as first-line treatment for excess weight and obesity and should be addressed at every visit. Given the physiological changes noted above, caloric intake may need to be adjusted as weight loss occurs. The ultimate goal of weight loss is to optimize patient health outcomes; total body weight loss goals differ based on comorbidities.

2 For example, 5% to 15% total body weight loss is recommended for overweight or obese persons with type 2 diabetes, hypertension, or dyslipidemia, while up to 40% is recommended for metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis (see Table 1).

2

The 2016 American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists and American College of Endocrinology (AACE/ACE) Clinical Practice Guidelines for Obesity and the 2022 American Gastroenterological Association (AGA) Clinical Practice Guideline on Pharmacological Interventions for Adults with Obesity recommend that pharmacotherapy be considered in combination with lifestyle interventions in patients with a body mass index (BMI) ≥27 kg/m2 with weight-related comorbidities (diabetes, hypertension, dyslipidemia, etc.) or with a BMI ≥30 kg/m2.

2,6 These guidelines provide a comprehensive summary of weight management agents, although newer agents have become available since publishing.

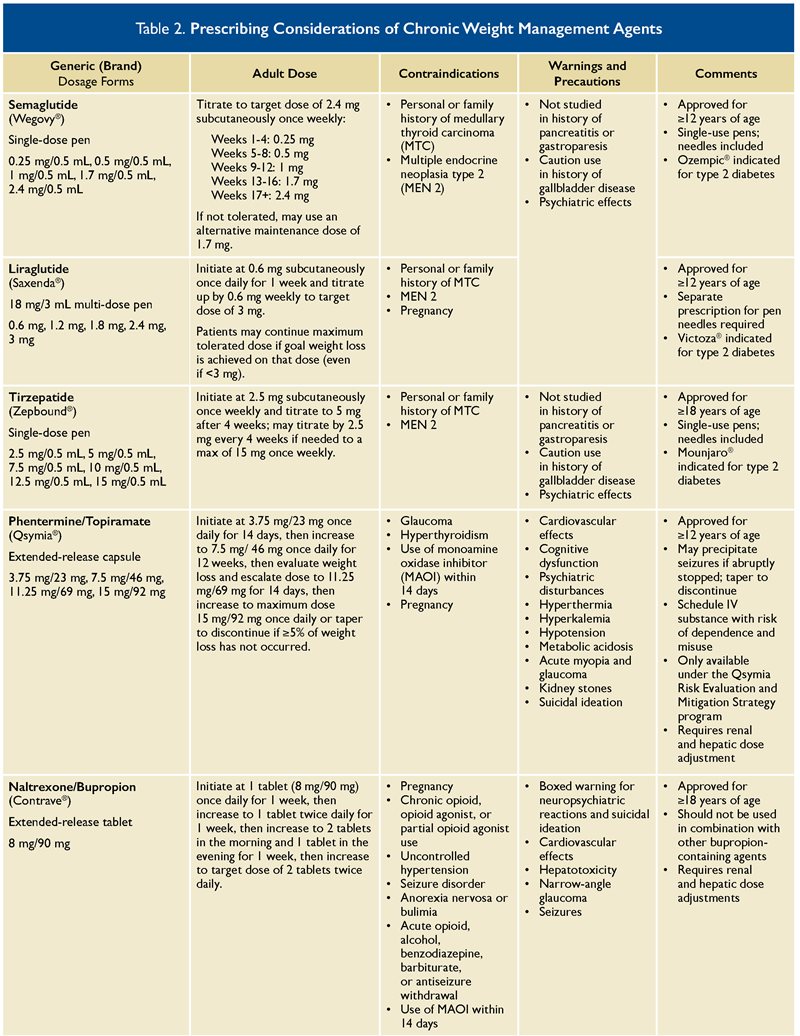

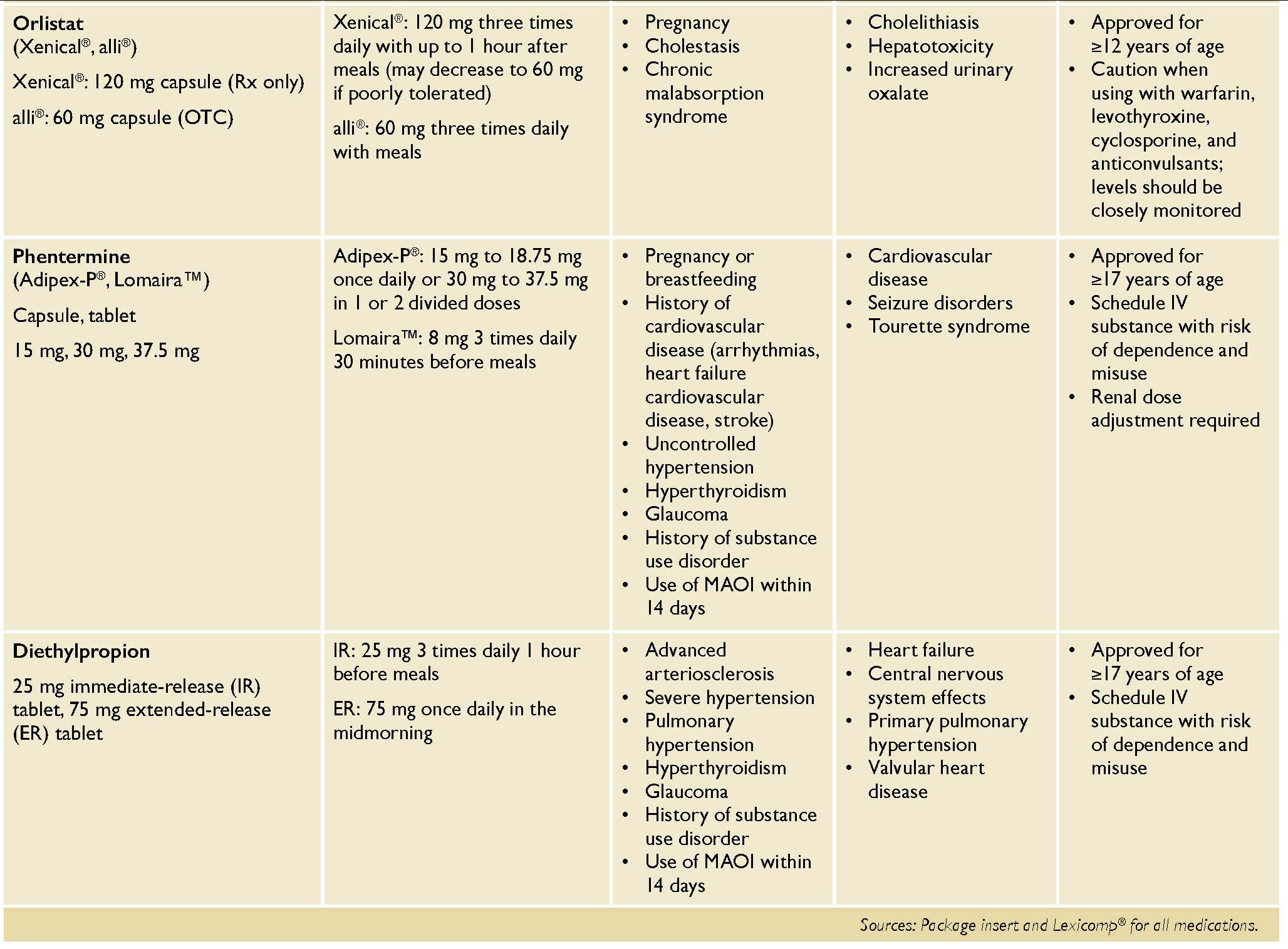

Currently approved agents for weight management include anorexiants (e.g., phentermine, diethylpropion), orlistat, phentermine/topiramate extended release (ER), naltrexone/bupropion ER, liraglutide, semaglutide, and tirzepatide. Initial pharmacotherapy choice should be based on patient preferences and existing comorbidities, as well as contraindications and prescribing considerations such as those listed in Table 2. Medications such as setmelanotide for obesity due to specific genetic disorders are not included in this review.

Orlistat is an oral agent that decreases the intestinal absorption of dietary fat and is available both over-the-counter (alli

®) and via prescription (Xenical

®). In the Xenical

® in the Prevention of Diabetes in Obese Subject (XENDOS) trial, treatment with orlistat 120 mg three times daily for one year resulted in weight loss of 10.6 kg compared to 6.2 kg with placebo (p <0.001).

7 A significantly greater reduction in weight with orlistat compared to placebo was sustained after four years of treatment, 5.8 kg versus 3.0 kg, respectively. Due to its mechanism of action, it must be used in combination with a low-fat diet (≤30% of daily calories from fat) to reduce gastrointestinal adverse events, and therapy with this agent necessitates use of a multivitamin that includes fat-soluble vitamins (A, D, E, K, and beta carotene) taken at least two hours before or after orlistat.

Gastrointestinal adverse reactions including bowel urgency and frequency, oily evacuation and rectal leakage, and flatulence with discharge can be bothersome. Given the small magnitude of benefit and risk of adverse reactions, the AGA guidelines suggest against the use of orlistat for patients who have excess weight or obesity.

6

Phentermine and topiramate ER (Qsymia

®) is a combination medication approved for chronic weight management. Phentermine is a sympathomimetic agent that decreases appetite through direct central nervous system stimulation, and topiramate acts by decreasing appetite and increasing satiety.

2 In a 56-week trial, patients with a BMI of at least 27 kg/m2 and two or more comorbidities (hypertension, dyslipidemia, diabetes, etc.) had a significant mean weight loss of 9.8% with phentermine/topiramate 15/92 mg per day versus 1.2% with placebo.

8 After 108 weeks of treatment, participants had a mean weight loss of 10.5% with the combination versus 1.8% with placebo (p <0.0001).

9

Additionally, about 70% of patients treated with phentermine/topiramate 15/92 mg per day achieved at least 5% weight loss after 56 weeks.

8,10 Phentermine/topiramate is a schedule IV controlled substance with a risk of dependence and misuse. It is only available through the Qsymia

® Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy (REMS) program due to the risk of birth defects and congenital malformations.

Naltrexone/bupropion ER (Contrave

®) is another combination agent that works on the appetite regulatory center in the brain to decrease food cravings and appetite.

2 The Contrave Obesity Research trials (COR-I and COR-II) included participants with a BMI of ≥27 kg/m2 with controlled hyperlipidemia and/or hypertension or a BMI of ≥30 kg/m2 for 56 weeks.

11,12 Participants in the COR-I trial receiving naltrexone/ bupropion ER 32/360 mg per day lost 6.1% of total body weight compared to 1.3% with placebo (p <0.0001).

11 Similarly, participants in the COR-II trial receiving naltrexone/bupropion ER 32/360 mg per day lost 6.4% of total body weight compared to 1.2% with placebo (p <0.001).

12

In the COR Intensive Behavior Modification trial, all treated patients received an intensive behavioral modification (BMOD) program in addition to naltrexone/bupropion ER or placebo. The intensive BMOD program included 28 group sessions that reviewed patients’ eating and activity logs, meal planning, problem solving, stimulus control, and other weight control topics. Intensive BMOD in combination with naltrexone/bupropion ER led to a significantly greater reduction in total body weight of 9.3% versus 5.1% with placebo.

13 Naltrexone/bupropion ER should be avoided in those with bipolar disorder, seizure disorders, history of anorexia, or with uncontrolled hypertension. Due to the naltrexone component, it must be avoided in patients taking chronic opioid therapy.

2

Liraglutide (Saxenda

®) and semaglutide (Wegovy

®) are both GLP-1 receptor agonists that increase satiety and decrease appetite. In the Semaglutide Treatment Effect in People with Obesity (STEP-1) trial, once-weekly semaglutide 2.4 mg resulted in a statistically significant mean weight loss of 14.9% versus 2.4% with placebo at week 68.

14 In the SCALE Obesity and Prediabetes trial, liraglutide 3 mg daily versus placebo for 56 weeks resulted in a statistically significant mean total body weight reduction of 8.0% versus 2.6%.

15 Between these two agents, semaglutide may be the preferred option given the once-weekly dosing and increased efficacy compared to liraglutide. The STEP-8 trial

16 demonstrated that after 68 weeks, semaglutide use resulted in a mean weight loss of 15.8% compared to 6.4% with liraglutide (p <0.001).

Semaglutide may also be preferred given the recently expanded labeling for cardiovascular risk reduction, which was the result of the Semaglutide Effects on Cardiovascular Outcomes in People with Overweight or Obesity (SELECT) trial.

17 Semaglutide (Wegovy

®) 2.4 mg once weekly resulted in a 20% relative risk reduction over 40 months in the composite cardiovascular end point (cardiovascular death, nonfatal myocardial infarction, or nonfatal stroke) in patients with established cardiovascular disease (CVD) on standard of care therapies (i.e., lipid-lowering therapy, beta blocker, antiplatelet, and/or angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor or angiotensin II receptor blocker).

Both agents have also been shown to be cardioprotective and reduce cardiovascular events in type 2 diabetes trials (although doses differed), so may be preferred in patients with established CVD or at high risk for CVD.

5 Gastrointestinal side effects such as nausea, vomiting, bloating, diarrhea, or constipation are most common with these agents, especially on initiation and dose escalation. These agents should be avoided in patients with gastroparesis, personal or family history of medullary thyroid carcinoma, and personal history of multiple endocrine neoplasia syndrome type 2 (MEN2).

Finally, tirzepatide (Zepbound

®) is the newest agent approved for chronic weight management from a novel class of agents. It is a GLP-1/GIP dual receptor agonist that increases satiety and decreases appetite.

18 In the Study of Tirzepatide in Participants with Obesity or Overweight (SURMOUNT-1) trial, tirzepatide was used in patients with a BMI of ≥27 kg/m2 with controlled hyperlipidemia and/or hypertension or a BMI of ≥30 kg/m2. This agent resulted in a statistically significant weight reduction (up to 20.9% versus 3.1% with placebo) at each of the three studied doses (5 mg, 10 mg, and 15 mg).

19

Tirzepatide 10 mg and 15 mg also resulted in a reduction in total body weight of up to 14.7% compared to 3.2% with placebo (p <0.0001 for all comparisons) in patients with a BMI of ≥27 kg/m2 and uncontrolled type 2 diabetes.

20 These findings suggest tirzepatide has more substantial weight management effect than any other currently available pharmacologic agent. The Tirzepatide versus Semaglutide Once Weekly in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes (SURPASS 2) trial found that tirzepatide was superior to semaglutide with body weight reductions of up to 13.1% compared to 6.7%, respectively.

21 However, no head-to-head data are available for use in obesity without type 2 diabetes.

Additional cardiovascular outcomes trials (CVOT) to assess cardiovascular safety, such as the Study of Tirzepatide Compared with Dulaglutide on Major Cardiovascular Events in Participants with Type 2 Diabetes (SURPASS-CVOT) trial, are ongoing and anticipated to be completed around June 2025. Prescribing precautions and adverse reactions for tirzepatide are similar to those for GLP-1 receptor agonists.

Anorexiants, such as phentermine and diethylpropion, are sympathomimetic agents that suppress the appetite through direct stimulation of the central nervous system. These stimulants are considered alternative agents and are approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for short-term use (≤12 weeks) only due to significant cardiovascular and psychiatric risks and the potential for misuse and dependence.

2,6 Although these agents are labeled for short-term use only, they have been studied off-label for up to two years with sustained efficacy and safety.

22,23 Clinicians should continuously monitor patients closely for cardiovascular side effects — such as increased heart rate or blood pressure and arrhythmias, psychosis, or new mood disorders — and signs of misuse/diversion if these agents are used long term.

Insurance coverage for weight management agents varies among plans and can be a barrier to initiation of therapy. In general, patients must have a BMI >30 kg/m2 or a BMI of >27 kg/m2 with at least one weight-related complication (such as hypertension, dyslipidemia, sleep apnea, etc.). Given the high cost of brand-name medications, many plans will require prior authorization, and some plans have stricter criteria such as BMI >35 kg/m2 or BMI >40 kg/m2 or may require documentation of at least six months of diet and lifestyle modification prior to coverage. The 2024 Pennsylvania Medicaid preferred drug list includes Zepbound

®, Wegovy

®, and Saxenda

® as preferred agents, but requires prior authorization. For oral agents, only phentermine is a “preferred” product — and still requires prior authorization — while the other oral agents are non-preferred medications.

24

Whether weight management is treated with lifestyle interventions only or in combination with pharmacotherapy, frequent follow-up and monitoring are essential to ensure the efficacy and safety of interventions. Most available agents require frequent titrations during initial therapy to ensure tolerability. The initial target for weight loss is at least 5% of body weight, with progressive reduction as treatment continues.

2,6

Weight should be monitored at every appointment to ensure efficacy, and if 4% to 5% weight loss has not been achieved following 12-16 weeks of therapy, the patient is considered a non-responder and the medication should be discontinued. Alternative therapies may be considered, however there are no data to suggest who is going to be a non-responder or whether those individuals will respond to other medications.

It is important to note that patients tend to regain weight that was lost when antiobesity medications are discontinued. For example, patients who were treated with tirzepatide or semaglutide regained about two-thirds of lost weight within one year after medication withdrawal.

25,26 For this reason, these agents should be treated as chronic medications, and clinicians should discuss this risk with patients prior to initiating, as well as discontinuing, these agents.

Results from a recent study on a tapering strategy of these injectable agents presented at the European Congress on Obesity showed that patients continued to lose weight during the taper and that weight loss was sustained for at least six months after the taper was completed.

27 Tapering, as opposed to abrupt discontinuation, may be a reasonable strategy to consider in patients desiring to discontinue these agents.

In summary, the management options for patients who are overweight and obese has drastically changed over the past few decades.

Obesity is recognized as a chronic condition and should be treated as such. Tirzepatide and semaglutide are the injectable agents that may be preferred given their increased efficacy and once-weekly dosing, with liraglutide being another efficacious injectable agent.

Phentermine/topiramate and naltrexone/bupropion may be alternative agents if oral medications are preferred, but contraindications should be carefully considered.

Orlistat may be the most accessible option for patients as it is available over-the-counter, but strict adherence to a low-fat diet is necessary to reduce side effects. Lastly, phentermine and other stimulant agents are alternatives typically recommended for short-term use if accessibility limits preferred agents, and they must be carefully monitored for misuse and cardiac or psychiatric side effects.

Comorbidities, concomitant medications, cultural beliefs, and social determinants of health should all be considered in ongoing weight management. Incorporating patient needs and desires into decision-making, and understanding how to navigate the insurance barriers and health care system, will increase the chance for weight loss and health maintenance for each patient.

REFERENCES

1.

REFERENCES

1. Obesity. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Accessed December 8, 2022.

https://www.cdc.gov/obesity/index.html

2. Garvey WT, Mechanick JI, Brett EM, et al. American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists and American College of Endocrinology comprehensive clinical practice guidelines for medical care of patients with obesity.

Endocr Pract. 2016;22(Suppl 3):1-203.

3. Domecq JP, Prutsky G, Leppin A, et al. Clinical review: drugs commonly associated with weight change: a systematic review and meta-analysis.

J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2015;100(2):363-370.

4. Dayabandara M, Hanwella R, Ratnatunga S, Seneviratne S, Suraweera C, de Silva VA. Antipsychotic-associated weight gain: management strategies and impact on treatment adherence.

Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2017;13:2231-2241.

5. American Diabetes Association Professional Practice Committee. 9. Pharmacologic approaches to glycemic treatment: standards of care in diabetes-2024 [published correction appears in Diabetes Care. 2024;47(7):1238].

Diabetes Care. 2024;47(Suppl 1):S158-S178.

6. Grunvald E, Shah R, Hernaez R, et al. AGA clinical practice guideline on pharmacological interventions for adults with obesity.

Gastroenterology. 2022;163(5):1198-1225.

7. Torgerson JS, Hauptman J, Boldrin MN, Sjöström L. Xenical in the prevention of diabetes in obese subjects (XENDOS) study: a randomized study of orlistat as an adjunct to lifestyle changes for the prevention of type 2 diabetes in obese patients [published correction appears in Diabetes Care. 2004;27(3):856].

Diabetes Care. 2004;27(1):155-161.

8. Gadde KM, Allison DB, Ryan DH, et al. Effects of low-dose, controlled-release, phentermine plus topiramate combination on weight and associated comorbidities in overweight and obese adults (CONQUER): a randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial [published correction appears in Lancet. 2011;377(9776):1494].

Lancet. 2011;377(9774):1341-1352.

9. Garvey WT, Ryan DH, Look M, et al. Two-year sustained weight loss and metabolic benefits with controlled-release phentermine/ topiramate in obese and overweight adults (SEQUEL): a randomized, placebo-controlled, phase 3 extension study.

Am J Clin Nutr. 2012;95(2):297-308.

10. Allison DB, Gadde KM, Garvey WT, et al. Controlled-release phentermine/topiramate in severely obese adults: a randomized controlled trial (EQUIP).

Obesity (Silver Spring). 2012;20(2):330-342.

11. Greenway FL, Fujioka K, Plodkowski RA, et al. Effect of naltrexone plus bupropion on weight loss in overweight and obese adults (COR-I): a multicentre, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial [published correction appears in Lancet. 2010;376(9741):594] [published correction appears in Lancet. 2010;376(9750):1392].

Lancet. 2010;376(9741):595-605.

12. Apovian CM, Aronne L, Rubino D, et al. A randomized, phase 3 trial of naltrexone SR/bupropion SR on weight and obesity-related risk factors (COR-II).

Obesity (Silver Spring). 2013;21(5):935-943.

13. Wadden TA, Foreyt JP, Foster GD, et al. Weight loss with naltrexone SR/bupropion SR combination therapy as an adjunct to behavior modification: the COR-BMOD trial.

Obesity (Silver Spring). 2011;19(1):110-120.

14. Khoo TK, Lin J. Once-weekly semaglutide in adults with overweight or obesity.

N Engl J Med.2021;385(1):e4.

15. Pi-Sunyer X, Astrup A, Fujioka K, et al. A randomized, controlled trial of 3.0 mg of liraglutide in weight management.

N Engl J Med. 2015;373(1):11-22.

16. Rubino DM, Greenway FL, Khalid U, et al. Effect of weekly subcutaneous semaglutide vs daily liraglutide on body weight in adults with overweight or obesity without diabetes: the STEP 8 randomized clinical trial.

JAMA. 2022;327(2):138-150.

17. Lincoff AM, Brown-Frandsen K, Colhoun HM, et al. Semaglutide and cardiovascular outcomes in obesity without diabetes.

N Engl J Med. 2023;389(24):2221-2232.

18. Zepbound

® [package insert]. Eli Lilly and Company; 2024.

19. Jastreboff AM, Aronne LJ, Ahmad NN, et al. Tirzepatide once weekly for the treatment of obesity.

N Engl J Med. 2022;387(3):205-216.

20. Garvey WT, Frias JP, Jastreboff AM, et al. Tirzepatide once weekly for the treatment of obesity in people with type 2 diabetes (SURMOUNT-2): a double-blind, randomised, multicentre, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial.

Lancet. 2023;402(10402):613-626.

21. Frías JP, Davies MJ, Rosenstock J, et al. Tirzepatide versus semaglutide once weekly in patients with type 2 diabetes.

N Engl J Med. 2021;385(6):503-515.

22. Cercato C, Roizenblatt VA, Leança CC, et al. A randomized double-blind placebo-controlled study of the long-term efficacy and safety of diethylpropion in the treatment of obese subjects.

Int J Obes (Lond). 2009;33(8):857-865.

23. Lewis KH, Fischer H, Ard J, et al. Safety and effectiveness of longer-term phentermine use: clinical outcomes from an electronic health record cohort.

Obesity (Silver Spring). 2019;27(4):591-602.

24. Medical Assistance Statewide Preferred Drug List. Pennsylvania Department of Human Services. January 8, 2024. Accessed September 25, 2024.

https://www.papdl.com/content/dam/ffs-medicare/pa/pdl/Penn-Statewide-PDL-2024v10.pdf

25. Aronne LJ, Sattar N, Horn DB, et al. Continued treatment with tirzepatide for maintenance of weight reduction in adults with obesity: the SURMOUNT-4 randomized clinical trial.

JAMA. 2024;331(1):38-48.

26. Wilding JPH, Batterham RL, Davies M, et al. Weight regain and cardiometabolic effects after withdrawal of semaglutide: the STEP 1 trial extension.

Diabetes Obes Metab. 2022;24(8):1553-1564.

27. Is Coming Off Semaglutide Slowly the Key to Weight Regain? European Association for the Study of Obesity. May 11, 2024. Accessed December 5, 2024.

https://easo.org/is-coming-off-semaglutide-slowly-the-key-to-preventing-weight-regain/