Winter 2020 - Vol. 15, No. 4

How Has COVID-19 Affected Patient Access

to Health Records at Penn Medicine LG Health?

Corey Meyer, MBA

Director, Strategic Acceleration

Penn Medicine Lancaster General Health

Jon Foley Sherman, PhD

Executive Assistant, Center for Health Care Innovation

Penn Medicine Lancaster General Health

Michael Sheinberg, MD

Chief Medical Information Officer

Penn Medicine Lancaster General Health

INTRODUCTION

The Internet has fundamentally shifted how Americans connect with one another, gather information, and conduct their daily lives. Ninety percent of Americans use the Internet to access financial accounts, send payments to people instantaneously, order groceries, book a haircut, make restaurant reservations, and – for many children during the global pandemic – receive K-12 schooling.1 The Internet has also changed how health care is accessed and provided throughout the world, including at Penn Medicine Lancaster General Health. Regulations like the 21st Century Cures Act will only increase this access by requiring expansion of patients’ access to their own records (see below).2 And, of course, the COVID pandemic has only increased the appetite for online access to health care, because it reduces the need for worrisome in-person encounters.

As many and as varied as the pandemic-induced changes have been at all levels of health care, the near-instant halt to in-person visits posed perhaps the greatest challenge to health care systems, quickly surpassing the problem of initial shortages in personal protective equipment. Clinics were temporarily shuttered entirely, and non-necessary procedures were put on hold. In the meantime, providers scrambled to find ways to connect with patients outside traditional clinical encounters.

These developments provided the impetus to reimagine how we provide care, often by using virtual connections, including virtual access to medical records by patients. In this article we look at one particular aspect of virtual contact between providers and patients – experience with digital interactions in MyLGHealth, the EPIC MyChart portal at Lancaster General Health. We’ll take a deeper dive into the demographics of our userbase, and we’ll review patients’ usage of online access in order to evaluate the benefits of continuing to make information and services available via the internet.

HISTORY OF PATIENTS’ DIGITAL ACCESS TO MEDICAL RECORDS AND HEALTH CARE SERVICES

In 2013, The Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association published a review of 27 studies conducted from 1970-2012 that studied how patient care and satisfaction was impacted by patient access to medical records.3 Although the review was unable to establish concrete benefits, the authors did find that clinicians’ fears of greater work burdens or increased patient anxiety were not borne out by the studies. As patient access to electronic medical records (EMR) becomes less a matter of “if” and more a matter of “how,” LG Health has undertaken a strategic approach to increasing digital access as much as possible.

Prior to the first user on MyLGHealth in 2008, patients could only access their own records by physically visiting their physician’s practice, or the centralized Medical Records Department at the main hospital. Patients could request photocopied versions of paper records, but these could be voluminous and difficult to comprehend, depending on the number of the patient’s previous interactions.4 In 2007, providers began using our EPIC electronic medical record system to document all interactions with patients, thus digitizing the data. Since 2008, MyLGHealth users can view all facets of their medical records including detailed provider notes, lab and imaging results, billing statements, and past appointment details. Patients can also request prescription refill requests, send secure messages to their care team, and pay medical bills.

Although informal phone calls to doctors for triage and medical advice have been a common practice for decades, not until 2010 could health care services be handled remotely and digitally via an e-visit at LGHealth. An e-visit involves asynchronous communication on a digital platform that allows remote care for minor conditions such as urinary tract or sinus infections.

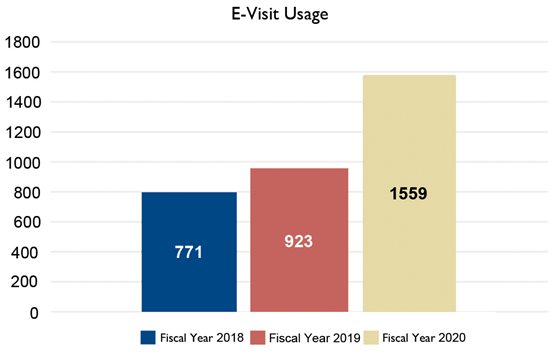

E-visits help avoid unnecessary office visits and simplify prescription fulfillment by allowing providers to determine whether a patient needs to be seen, or whether the prescription can be issued without the patient being seen in person. Patients answer electronic questionnaires about their condition and the provider then receives the responses within the electronic health record and responds with the appropriate next step. If necessary, a prescription is digitally sent to the patients’ preferred pharmacy. E-visits continue today as an option when asynchronous care is the appropriate clinical method of care, and they have increased in frequency in recent years (Fig. 1).

Fig.1. E-Vist usage in the last three fiscal years.

In 2019, video visits became available and patients and providers could interact during real-time audio and video appointments. The COVID-19 pandemic sped up adoption of video visits; from March to May 2010, nearly 90% of encounters with patients were handled virtually. COVID-19 advanced our digital interactions by offering telephonic and video visits when in-person visits were not necessary.

CURRENT STATE OF PATIENTS ACCESSING MEDICAL RECORDS AND HEALTH CARE SERVICES

Since 2008, MyLGHealth has offered an ever-increasing suite of functions. In the early years these included accessing test results, viewing details about past appointments, and sending messages to providers. Current additional functions including the ability to schedule appointments directly, pay medical bills, and schedule video visits with providers.

As of October 20, 2020, the Lancaster General Health system has 247,731 patients who can access their medical records and have health care delivered via MyLGHealth. According to a 2014 study in the Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved, 80% of family health care decisions are made by women,5 which may account for the fact that 60% of all users of MyLGHealth are female. For patients under 13 years of age, portal access is limited to an adult caregiver. This age group is the only cohort for which access is approximately equal for males and female patients. The assumption is that female caregivers (including mothers) are interacting with records of male and female children equally.

Females comprise 67% of users in the 25- to 34-year-old cohort, which corresponds to typical child-birthing years for women in our system (Table 1). In the 35- to 64-year-old cohort, the percentage of female users stays fairly consistent at around 60%. As the tech-savvy younger generations grow older and consume more health care services, we expect an increasing percentage of patients to use MyLGHealth.

Table 1. Patient demographics by age and gender for MyLGHealth as of July 31, 2020.

Table 1. Patient demographics by age and gender for MyLGHealth as of July 31, 2020.

USAGE OF THE PATIENT PORTAL

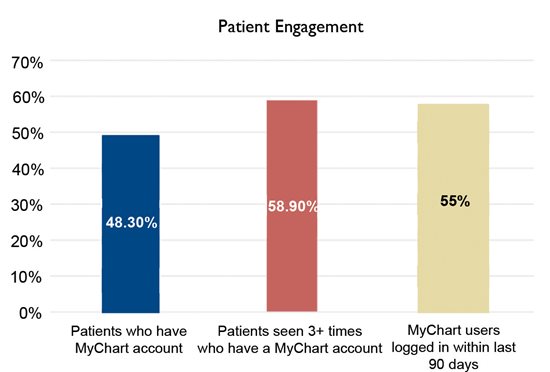

A key metric of engagement is that 48.3% of patients who had a visit in the last 12 months have a MyLGHealth account. For those who had 3 or more visits in the past 12 months, the percentage increases to 58.9% (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2. Patient engagement data for MyLGHealth

Looking at the numbers from the reciprocal perspective, 55% of patients who have an account have logged in within the last 90 days. The most common reason for doing so is to access lab or imaging test results, which was done by 55% of users.

PROVIDER BURDEN OF SHARING NOTES

The 21st Century Cures Act of 2016 requires patients to have electronic access to their complete electronic medical records. The regulations give patients easier access to information about their care, including the notes their clinicians write, a program commonly referred to as “open notes.” 6 Slightly more than half of patient notes (51.3%) are currently shared by providers in our patient portal.

A web-based survey of 1,628 clinicians explored the provider burden of sharing notes,7 and concluded that “most viewed note sharing positively (74% agreed that it is a good idea and 74% viewed shared notes as useful for engaging patients in their care), and 37% of physicians surveyed reported spending more time in documentation. Physicians with more years in practice and fewer hours spent in patient care had more positive opinions overall.” Thirty-six percent of clinicians (463) reported spending more time writing their notes because of open notes, while 63% (808) reported no change or spending less time. Compared to specialists, primary care physicians more often stated that they would recommend the practice to colleagues (PCP, 64% vs specialist, 54%; P = .008).

PATIENT PERCEPTIONS OF HAVING ACCESS TO DATA

Surveys of patient attitudes to online portals provide further insight into patient engagement with their personal records. In 2016, researchers at Virginia Commonwealth University Health System (VCUHS) surveyed patients who were already using their portal, and captured the views of 23% of all patients who viewed the survey on the portal.8 Among these, 64% (957) were aware that their records were available on the portal and had accessed them. Of patients using the portal, 50% were 30-59 years, and 40% were 60 years old or more. Sixty percent had at least a college degree.

A substantial majority (83%) felt that access to their records helped them take better care of themselves, and 94% felt it did not increase their concern. Although 71% felt that portal access did not affect how often they contacted their providers, 20% felt it was decreased, while 10% felt it was increased.

THE FUTURE

Access by patients to their own digital medical records and to medical services is here to stay, and we expect it to increase over time. Older patients are not showing resistance to using the new technology, and younger, more tech-savvy generations, who are already plugged into their health care online, will use health care services more as they age. Patients will expect near real time access to their information, and expect real time and asynchronous care as needed. And providers will recognize that their fears about increased burdens or uncompensated patient contacts are unfounded.

These trends indicate that the next round of research on access to patient records should be designed not only to understand past and current usage, but to target areas of patient experience that can be improved. We know that an improved patient experience can lead to better outcomes of care, but we don’t know precisely what “access” means to our patients. What kind of and how much access do our community’s patients – who will not necessarily have the same interests as those in other communities – actually want? Perhaps most importantly, can we design research that will allow us to better understand if and how patient access to the information actually improves quality? These and other questions will surely be answered before long.

REFERENCES

1. https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/fact-sheet/internet-broadband/

2. https://www.congress.gov/bill/114th-congress/house-bill/34

3. Traber DG, Menon S, Parrish DE, et al. Patient access to medical records and healthcare outcomes: a systematic review. J Am Med Informatics Assoc. 2014; 21 (4): 737-741. https://doi.org/10.1136/amiajnl-2013-002239 https://academic.oup.com/jamia/article/21/4/737/762824

4. Jaspers AW, Cox JL, Krumholz HM. Copy fees and limitation of patients’ access to their own medical records. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(4):457–458. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.8560 https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamainternalmedicine/article-abstract/2599438%20%20%20.

5. Matoff-Stepp, S, Applebaum, B, Pooler, J, et al. Women as health care decision-makers: implications for health care coverage in the United States. J Health Care for the Poor and Underserved. 2014; 25(4): 1507-1513. doi:10.1353/hpu.2014.0154. https://muse.jhu.edu/article/561554.

6. Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology. 21st Century Cures Act: Interoperability, Information Blocking, and the ONC Health IT Certification Program. Published 2020. https://www.healthit.gov/cerus/sites/cerus/files/2020-03/ONC_Cures_Act_Final_Rule_03092020.pdf

7. DesRoches CM, Leveille S, Bell K, et al. The views and experiences of clinicians sharing medical record notes with patients. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(3):e201753. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.1753 https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamanetworkopen/fullarticle/2763607

8. Mishra VK, Hoyt RE, Wolver SE, et al. Qualitative and quantitative analysis of patients' perceptions of the patient portal experience with opennotes. Applied Clinical Informatics. 2019 Jan; (10)1: 10-18. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6327733/