Winter 2020 - Vol. 15, No. 4

Fourth Trimester Care

Timely Intervention for Postpartum Needs

Brianna Moyer, M.D.

Associate Director, Family Medicine Residency Program

Penn Medicine Lancaster General Health

Family and Maternal Medicine

INTRODUCTION

The fourth trimester, defined as the 12 weeks following the delivery of a child, is a critical time in a woman’s life. Physicians readily recognize the importance of frequent prenatal care in preventing complications of pregnancy. However, more than 50% of pregnancy-related maternal deaths occur after delivery, demonstrating that comprehensive postpartum care is crucial to reducing maternal morbidity and mortality.1 Additionally, women experience multiple physical, mental, emotional, and social changes following birth. Navigating these changes, as well as learning to care for a newborn, present challenges that affect the health and well-being of the mother. Early, coordinated, and comprehensive care during the fourth trimester lays the foundation for a mother’s long-term wellness in the postpartum period and beyond.

THE STANDARD MODEL OF POSTPARTUM CARE

Traditionally, physicians in the United States have seen women for a single postpartum visit between four to six weeks after delivery. This visit often served to close the relationship between the prenatal provider and the patient, even though pregnancy complications and chronic medical conditions increase the mother’s morbidity and mortality during and after the postpartum period. Post-delivery concerns include secondary postpartum hemorrhage, endometritis, thromboembolic disease, hypertensive disorders, postpartum depression, intimate partner violence, and problems related to breastfeeding.

More than half of postpartum strokes occur within 10 days of discharge.1 Additionally, 20% of women who experience undesired weaning report that they discontinued breastfeeding by six weeks postpartum.1 These statistics suggest that women experience medical complications prior to the traditional postpartum visit at four to six weeks after delivery.

In addition to medical concerns, women encounter social and emotional challenges in the postpartum period. In 2012, 23% of women returned to work within 10 days postpartum and 22% returned to work between 10 to 40 days postpartum.2 Therefore, many women scheduled within the traditional time frame have already returned to work and do not have the opportunity to receive supportive and anticipatory counseling related to that transition. A single postpartum visit at four to six weeks after delivery limits the ability of the physician to evaluate for postpartum complications, and to provide appropriate anticipatory guidance.

RECOMMENDATIONS FOR EARLY POSTPARTUM CARE

In 2018, The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) published a committee opinion proposing a revised model of postpartum care. ACOG recognized that postpartum care requires ongoing communication between the woman and her physician.

Rather than a single postpartum visit 4-6 weeks after delivery, ACOG recommended that all women have contact with their prenatal provider within 3 weeks of delivery, and have a comprehensive postpartum visit no later than 12 weeks after birth (Fig.1). Additionally, ACOG emphasized the importance of a smooth transition from postpartum care to well woman care.

Fig.1. Ongoing communication between a woman and her physician can address pregnancy-related issues as well as chronic medical conditions.

If the prenatal care provider does not serve as the patient’s primary care physician, that provider should assist the patient to connect with a primary medical home.

This transition from a single postpartum visit to an ongoing relationship throughout the fourth trimester allows the physician to address pregnancy-related complications and chronic medical conditions that impact a woman’s long-term health.

COMPONENTS OF POSTPARTUM CARE

ACOG recommends that providers address the following components during postpartum care:1

• Mood and emotional well-being: screen for postpartum depression and anxiety, follow-up on pre-existing mental health diagnoses, and connect patients with local resources as needed;

• Infant care and feeding: ask about the infant’s method of feeding, address concerns about breastfeeding, and confirm that the infant has a medical home;

• Substance use: screen for tobacco and substance use disorders and refer as indicated;

• Resource assessment: assess for material needs, such as appropriate housing or supplies for the baby, and refer as indicated;

• Contraception and birth spacing: offer guidance about sexuality and resumption of intercourse, discuss appropriate birth spacing, and provide unbiased counseling about available methods of contraception;

• Sleep and fatigue: assess the patient’s support system and discuss strategies for addressing fatigue and sleep disruption;

• Physical recovery after birth: evaluate perineal lacerations or cesarean incisions, assess for urinary or fecal incontinence, and offer guidance for resumption of physical activity and weight management;

• Chronic disease management: review compatibility of medications and supplements with breastfeeding, discuss any pregnancy-related complications and their implications for future reproductive and overall health, and connect the patient with a medical home for on-going care;

• Health maintenance: update immunizations and provide age-appropriate cancer screening as indicated.

In addition to ACOG’s recommendations, the USPSTF recommends that providers screen all women of reproductive age for intimate partner violence using a validated tool.3 The postpartum period is an appropriate time for such screening, and if a patient screens positive, the physician should provide appropriate resources and referrals.

SPECIFIC MEDICAL CONDITIONS IN the POSTPARTUM PERIOD

Hypertensive Disorders

Hypertension and preeclampsia contribute to high rates of maternal morbidity and mortality in the United States.4 Preeclampsia can present in the antepartum or postpartum period; the reported prevalence postpartum ranges from 0.3% to 27.5%.4 Symptoms of postpartum preeclampsia typically present between 48 hours to six weeks postpartum, and 10% of maternal deaths from hypertension occur in the postpartum period.5 Therefore, postpartum visits within three weeks of delivery that include blood pressure screening can help to identify cases of postpartum preeclampsia.

For women diagnosed with antepartum preeclampsia or other hypertensive disorders of pregnancy, ACOG recommends a blood pressure evaluation within seven to ten days of delivery. This early visit allows physicians to evaluate for appropriate blood pressure control to prevent complications such as stroke or seizure. The diagnosis of a hypertensive disorder of pregnancy increases the risk of cardiovascular disease later in life.3 Providers should counsel women about the risks associated with hypertensive disorders of pregnancy and the implications for future reproductive and overall health.

Gestational Diabetes

Women with a diagnosis of gestational diabetes are 8 – 20X more likely to develop type II diabetes in their lifetime.3 Providers should order a 75 gm. two-hour fasting oral glucose tolerance test, or a fasting plasma glucose level, at 6 – 12 weeks postpartum for all women with a diagnosis of gestational diabetes. A positive test indicates impaired glucose tolerance and warrants appropriate preventive therapy. Women with a negative test require screening for diabetes every three years for the remainder of their lifetime.

Postpartum Depression

In the first year postpartum, up to 10% of women will experience symptoms of depression.3 Providers should use validated tools such as the Patient Health Questionnaire-2 (PHQ-2), the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9), or the Edinburgh Postpartum Depression Scale, to screen for postpartum depression. If symptoms of postpartum depression are identified, the provider should connect the patient with appropriate resources, which may include medication therapy, counseling services, or a social work referral.

HEALTH DISPARITIES IN THE POSTPARTUM PERIOD

In the United States, black women die from pregnancy-related complications at three to four times the rate of white women.6 A study assessing the disparities of prenatal and postpartum care in the Pennsylvania Medicaid Program demonstrated that white and Asian women have higher odds of receiving prenatal and postpartum care than black women.7 These results were consistent with national statistics.

Women of color may also experience mistrust of the health care system that affects their willingness to disclose symptoms of postpartum depression and other concerns to health care providers.8 Comprehensive postpartum care that includes a trusting, ongoing relationship between a woman and her provider can help address health disparities in maternal morbidity and mortality.

ADDRESSING MATERNAL MORTALITY IN PENNSYLVANIA

Pennsylvania ranks 24th in maternal mortality in the country.7 The Pennsylvania Perinatal Quality Collaborative (PAPQC) is a working group of birth sites, NICUs, and health plans in Pennsylvania that was created in April 2019 “with a focus on reducing maternal mortality and improving care for pregnant and postpartum women and newborns affected by opioids.” 9 In alignment with ACOG’s 2018 committee opinion on postpartum care, the PAPQC has recognized the role of postpartum care in reducing maternal morbidity and mortality. The PAPQC has identified fourth trimester care as a quality metric, and is tracking how many women have contact with their prenatal provider within three weeks of delivery. The PAPQC aims to use this information to create best practices for prenatal providers.

FAMILY MEDICINE AND POSTPARTUM CARE

Family medicine physicians who provide prenatal care are in a unique position regarding implementation of a fourth trimester care model. Because family physicians have the ability to care for both the mother and her newborn, family practices can implement a model in which mothers and newborns can both be seen by one provider in the early postpartum period. Up to 40% of women do not attend a postpartum visit,1 but a mother often accompanies her newborn for well child visits. Scheduling the mother and child for adjoining appointments can help to increase postpartum visits and reconnect the mother with the health care system.

IMPLEMENTATION OF A FOURTH TRIMESTER MODEL IN A RESIDENCY PRACTICE

As a member of the IMPLICIT network, the Penn Medicine Lancaster General Health Family Medicine Residency Program is serving as a pilot site to assess the feasibility of a proposed fourth trimester care model. The IMPLICIT network is a “family medicine maternal child health learning collaborative” created by family physicians within the Family Medicine Education Consortium (FMEC). IMPLICT specifically stands for “Interventions to Minimize Preterm and Low birth weight Infants using Continuous quality improvement Techniques.” 10 The LGH Family Medicine Residency Program participates with other residencies and health systems to implement quality improvement focused on “improving birth outcomes and promoting the health of women, infants, and families.”

The IMPLICIT Network recently proposed a fourth trimester care model that includes screening women for medical and social risk factors during the third trimester, at the time of delivery, and within three weeks postpartum. Downtown Family Medicine and Family and Maternity Medicine served as pilot sites for implementation of this care model. To assess the feasibility of this model, a team of residents and faculty identified 27 prenatal women from the Downtown Family Medicine and Family and Maternity Medicine clinics. The team surveyed these women about prenatal and postpartum risk factors, including chronic medical conditions, depression, intimate partner violence, and substance use. Women with identified risk factors were connected with appropriate resources. The team also attempted to schedule all of the women for postpartum follow-up within three weeks of delivery (Fig. 1). Compared with a baseline rate of attendance and timing of post-partum follow-up, the study group had a slightly higher rate of postpartum follow-up within three weeks.

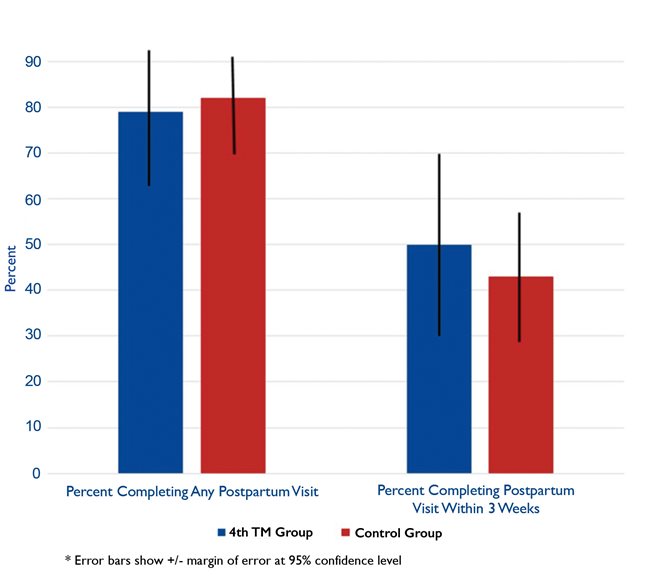

In the 4th Trimester Group, 79% (+/- 19%) of participants completed any postpartum visit, vs. 82% (+/-11%) in the control group; 50% (+/-20%) of 4th Trimester participants completed a postpartum visit within 3 weeks compared with 43% (+/-14%) in the control group.

None of these differences were statistically significant, likely due to the small sample size.

The team has started a qualitative review of the pilot study to assist in implementing this 4th Trimester care model as the standard of care for all prenatal patients in the residency clinical practices. During the initial review, the team discovered that the surveys used during the pilot study helped to identify risk factors for several women that had not been previously recognized during routine prenatal care. The team plans to implement a care model that will include early postpartum visits within three weeks of delivery, comprehensive postpartum visits within 12 weeks of delivery, and standard screening for risk factors in the third trimester, at delivery, and at the early postpartum visit. To better facilitate follow up, the team hopes to develop a strategy for scheduling coordinated appointments for mother and child.

CONCLUSION

The traditional model of postpartum care is inadequate for addressing the needs of women during the fourth trimester. Given the high rate of maternal morbidity and mortality in the United States compared with other developed countries, it is imperative that providers of prenatal care recognize the importance of comprehensive postpartum follow-up. Health care providers trained in obstetrical care should facilitate early postpartum follow-up, a comprehensive postpartum visit within 12 weeks of delivery, and connection with a primary medical home for ongoing well woman care for all women.

REFERENCES

1. Presidential Task Force on Redefining the Postpartum Visit. ACOG Committee Opinion. Optimizing postpartum care. Ob Gyn. 2018; 131(5): e140-e150. https://www.acog.org/-/media/project/acog/acogorg/clinical/files/committee-opinion/articles/2018/05/optimizing-postpartum-care.pdf

2. Klerman J, Daley K, Pozniak A. Family medical leave in 2012: Technical report. Cambridge (MA): ABT Associates Inc; 2014.

3. Paladine, H, Blenning C, Strangas Y. Postpartum care: An approach to the fourth trimester. Am Fam Phys. 2019; 100(8):485-491.

4. Redman E, Hauspurg A, Hubel C, et al. Clinical course, associated factors, and blood pressure profile of delayed-onset postpartum preeclampsia. Ob Gyn. 2019; 134(5):995-1001.

5. Ybarra N, Laperouse E. Postpartum preeclampsia. J Ob Gyn Neonatal Nursing. 2016;45:S20. https://www.jognn.org/article/S0884-2175(16)30067-3/pdf

6. Essien U, Molina R, Lasser K. Strengthening the postpartum transition of care to address racial disparities in maternal health. J Natl Med Assoc.https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30503575/

7. Parekh N, Jarlenski M, Kelley D. Prenatal and postpartum care disparities in a large Medicaid program. Matern Child Health J. 2018; 22:429-237.

8. Tully K, Stuebe A, Verbiest S. The fourth trimester: a critical transition period with unmet maternal health needs. Am J Ob Gyn. 2017; 217(1):37-41. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28390671/

9. Pennsylvania Perinatal Quality Collaborative. https://www.whamglobal.org/papqc

10. IMPLICIT Network. https://www.fmec.net/implicit