Winter 2020 - Vol. 15, No. 4

Early History of Surgery in Lancaster County

and the Lancaster General Hospital

Edward T. Chory, MD, FACS

“Surgery is a profession defined by its authority to cure by means of bodily invasion. The brutality and risks of opening a living person's body have long been apparent, the benefits only slowly and haltingly worked out.”

— Atul Gawande, MD, MPH 1

Author’s Note: Much has changed in both medicine and surgery since I started my surgical training in New York City in 1980. At a time when the AIDS epidemic was exploding, outpatient surgery was born, and technology—from computed tomography (CT) scans to nuclear magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)—changed how we diagnosed many diseases. Transplant surgery became commonplace, and the pharmaceutical industry began to increase our therapeutic armamentarium to a previously unimaginable scope. Technology has also had an enormous impact on medical and surgical procedures, such as endovascular stents and robotic surgery.

I came to Lancaster in 1991 at the dawn of laparoscopic general surgical techniques, which proved to be almost as revolutionary as the discovery of anesthesia.1

Readers who want more detailed information about the topics discussed in this article should consult the sources I primarily relied on: Our Medical Heritage, published in 1994 by the Lancaster City & County Medical Society; Dr. Henry Wentz's 1993 A History of Lancaster General Hospital in Celebration of its 100th Anniversary; and Dr. Ira Rutkow’s Surgery: An Illustrated History, published by Mosby in 1994.2

INTRODUCTION TO THE HISTORY OF SURGERY

Until the development of anesthesia, asepsis, and antibiotics, pain and the risk of infection were barriers to safe and humane surgical practice everywhere. Important points of local surgical history include:

• The first physician to practice in Lancaster County was Hans Neff (later changed to Dr. John Henry Neff). He fled Switzerland and settled near the Conestoga River on land granted to him by William Penn sometime before 1715. Known as “the Old Doctor,” he both practiced medicine and operated a mill.3

• Henry Carpenter (formerly Zimmerman) settled in West Earl Township in 1717.4

• The great-great grandson of Dr. Henry Carpenter (the fifth generation Dr. Henry Carpenter) was President James Buchanan's personal physician.4

For many years after the first settlement in Lancaster County, there were few physicians and no apothecaries in this area; the treatment of disease and the preparation of medicines were in the hands of those who had little or no training for such serious work, but who nevertheless did the best they could. In colonial times only 5% of physicians had a university degree. Each community contained midwives; internists who gathered, sold, and prescribed herbs; and surgeons, who performed cupping and bleeding. (The practice of bloodletting has been extensively discussed in a previous article in this journal.5 ) Early apothecaries and medical care were provided from homes like the Musser home.6

THE ATLEE FAMILY

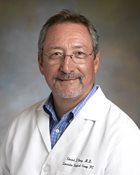

Fig. 1. Dr. John Light Atlee ,

born in 1799, practiced medicine

in Lancaster his entire career.

He was elected vice president

of the American Medical

Association at age 83.

In the 1800s, Lancaster laid the foundation of its reputation for excellent medical and surgical care. Dr. John Light Atlee (Fig. 1) was born in 1799 and graduated from the University of Pennsylvania in 1820. He practiced medicine and surgery in Lancaster his entire life and at the age of 83 was elected vice-president of the American Medical Association (AMA).7 His inaugural address included this advice:

“Above all things, ever strive to maintain the honor of the profession…At the close of a long life, one devoted unreservedly to the study and practice of medicine, I will say that notwithstanding its uncertainties, its fatigues, its anxieties, its disappointments, I am completely satisfied that in no other way can a man more fully accomplish his sole duty to God and to his fellowman; so that when life is ended, it can truly be said: ‘He went about doing

good.’ ” 7

Dr. J.L. Atlee and his brother, Washington Lemuel, performed ovariotomies in the 1840s, a procedure felt to be cruel and murderous by the majority of contemporary surgeons.8 A description of the procedure was published in 1844 in the American Medical Journal. Dr. Elmer Prizer's address to commemorate the 90th anniversary of the Lancaster City & County Medical Society included this comment:

“The patient was told by her friends and family that, if Dr. Atlee operated on her and she died, they would bring charges of murder against him, of which charges he was perfectly familiar before he assumed the responsibility of the operation.” 7

When one reflects upon the violent opposition of the profession and laymen at the time, and that it was murderous to attempt this operation, one marvels at the courage, fortitude, unusual force of character, determination, and nerves of steel needed to operate in the face of such public sentiments. At this time there was little knowledge of anesthesia or asepsis. Before Pasteur’s germ theory, Koch’s work with tuberculosis and other microorganisms, and Lister’s aseptic techniques, there was no antisepsis, nor were there any trained nurses in Lancaster. The only public hospital was the Lancaster County Hospital. Most other operations took place on kitchen or dining room tables, or in private hospitals, such as the Musser Home.6 An example of such a dining room procedure was documented in Dr. Elmer Prizer’s toast:

“The patient, who was twenty-seven years of age, received the night before the operation ten drops of McMunn’s elixir of opium. The operation was performed on a dining room table, and the patient was told to cry out if much pain was inflicted. The incision of the skin called forth a cry of pain, but the later stages of the operation caused little suffering. A median line incision through the abdominal wall was made, and both ovaries removed. Each ovary weighed about one pound, and the fluid taken away weighed twenty pounds. The sutures and ligatures used were silk and leather with the ends carried through the abdominal wound, permitting them to slough away. The operation was performed in June, and the last ligature came away in October. The patient recovered and lived for fifty years longer. The operation opened an avenue for a brilliant career which he achieved throughout the country. For a time following this operation, he was called a murderer and carried a sword cane as a matter of self-defense.” 7

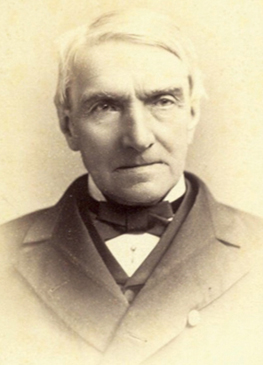

Fig. 2. Dr. William Worall Mayo (left),

father of William and Charles Mayo,

founders of the Mayo Clinic, visited

Lancaster to observe the Atlee

brothers perform ovariotomies.

The reputation of John L. Atlee and Washington L. Atlee was such that William Worall Mayo (Fig. 2), the father of William and Charles Mayo, founders of the Mayo Clinic, visited Lancaster to observe ovariotomies performed by the Atlees.8 The Atlees' last days were "made happy in the reception of professional honors and the assurance and high esteem and regard from those who had most strenuously opposed them.” 8

Other important Atlee medical notes include:

• John Light Atlee was truly a renaissance man, and was instrumental in minimizing the scourge of cholera in Lancaster by working with the Sanitary Committee of Lancaster County to establish a clean, public water supply. 8

• The Lancaster City & County Medical Society was established in 1844, more than 20 years after it was first proposed. Dr. John L. Atlee served as its president twice.8

• During the influenza epidemic of 1918, Dr. John Atlee Sr. was the director of the Emergency Hospital and faced an influenza mortality rate of around 33%.9

OTHER IMPORTANT LANCASTER MEDICAL FIGURES

Dr. George Kerfoot, a native of Dublin, Ireland, was born in 1808 and came to Lancaster at age 10. At 15, he began to study medicine under Dr. Samuel Humes, the first president of the Lancaster City & County Medical Society. By age 21, Kerfoot had received a degree from Jefferson Medical College and returned to Lancaster to practice medicine. At that time there were only 18 physicians to serve a town of 7,704 people. In response to the need for more medical expertise, and with his intense interest in anatomy, Dr. Kerfoot opened the Anatomic Hall on South Queen Street in 1833 where he gave public lectures and offered courses in anatomy. He was also known to raid Potter’s field, the public cemetery, for corpses to dissect.8

Many famous surgeons were born in Lancaster County, but many did not stay to practice here. These included surgeons such as Dr. John Deaver, who performed more than 15,000 appendectomies,7 and Dr. Jonathan Foltz, who was surgeon general under President Ulysses S. Grant.7

David Hayes Agnew, who was immortalized in the Eakins painting of the Agnew Clinic,10 was a prominent surgeon who was born in Nobleville (now Christiana) and practiced there under his father for two years before moving to Philadelphia.10

LANCASTER HOSPITALS

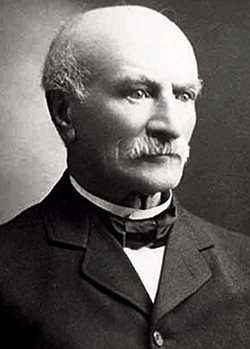

Fig. 3. The Lancaster County Hospital, built on East King Street 1799-1801, also

served as a poor house. It is considered to be the second oldest hospital in the

United States still in existence, predated only by the Pennsylvania Hospital in Philadelphia.

The Lancaster County Hospital was built from 1799 to 1801. (Fig. 3) It is considered to be the second oldest hospital extant in the United States, and is antedated only by the Pennsylvania Hospital in Philadelphia. While technically called a hospital, it served as more of a shelter or almshouse in its time, and was founded by “the Directors of the Poor and House of Employment.” 11

St. Joseph's Hospital was founded in 1883 by the Sisters of St. Francis of Philadelphia.12 At age 84, Dr. John Light Atlee became its first medical director.8

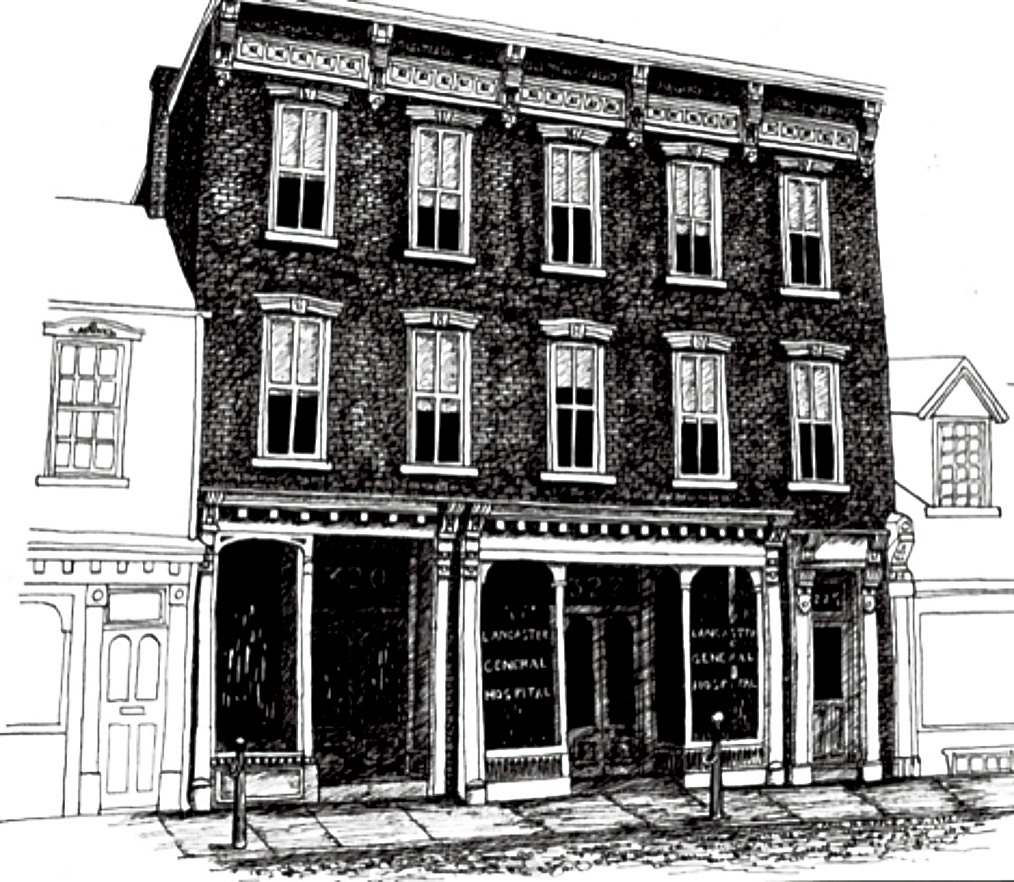

LANCASTER GENERAL HOSPITAL

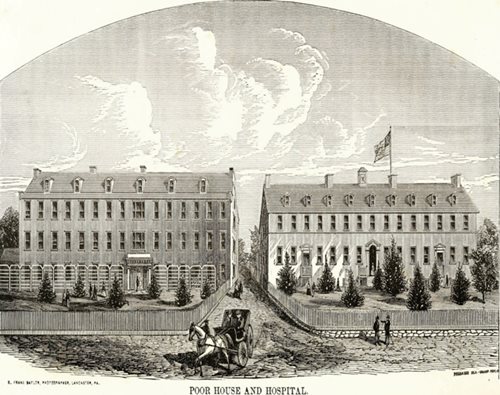

Fig. 4. The original Lancaster

General Hospital was founded

in 1893 in this small home at

322 N. Queen St. Associating

hospitalization with death,

most of Lancaster’s population

preferred to have their medical

and surgical treatments at

home.

In 1893, Lancaster General Hospital (LGH) was founded in a small home at 322 N. Queen St., Lancaster,

Pa.9 (Fig. 4). Around this time, the population of Lancaster City was 32,000 and Lancaster County’s population totaled 150,000. With the widely held view that hospitalization was associated with death, most of Lancaster’s population preferred to have their medical and surgical treatments at home.9

During the first five years of its operation, 541 patients – 308 surgical and 233 medical – were admitted to LGH. The mortality rate was 5% (16/308) for surgical procedures, and 51% (118/233) for medical patients.9 The most

common operations were appendectomies, amputations, and the drainage of abscesses.9

With the discovery of anesthesia by Drs. Morton, Wells, and Bigelow, and the discoveries by Drs. Semmelweiss, Lister, and Pasteur that provided an understanding of infectious diseases and the importance of antisepsis in surgery, hospitals became a place to get well and to receive treatment that prevented death, rather than a place to die. Public health also made great strides in improving the quality of life in Lancaster.

By 1908, after 15 years of experience at Lancaster General Hospital, 701 abdominal operations had been performed, including 248 appendectomies, 13 cholecystectomies, and 39 inguinal herniorrhaphies. Other procedures included 192 bone operations, 42 joint operations, 761 gynecological procedures, 408 genitourinary operations, and 307 ear/nose/throat operations.9

Ten years later, as the Spanish flu epidemic was devastating Lancaster and the rest of the country, Dr. Solomon Pontius was an intern at Lancaster General Hospital. During his time there, on Oct. 17, 1918, the Lancaster Board of Health reported 2,516 cases of influenza in one day.9

In 1922, after a general surgery residency at the Mayo Clinic, Dr. Solomon Pontius returned to Lancaster and brought the canopy system used at the Mayo Clinic for operating room organization.9 Dr. Pontius was the chairman of the LGH Department of Surgery from 1939 to 1957, and was the first physician appointed to the Board of Directors of Lancaster General Hospital.9

Pontius’s introduction of the canopy system, and other improvements, helped improve the public’s perception of hospitals. The introduction of automobiles, and the accompanying increase in traumatic injuries, gave hospitals more opportunities to prove their worth. Citizens began accepting the idea of seeking out hospitals for sickness, injuries, and childbirth.9

Other important milestones include:

• In 1922, Dr. Joseph Appleyard completed his internship at Lancaster General Hospital. With some additional surgical training, he became the first physician to practice urology in Lancaster County and joined the LGH staff in 1926. Aside from his medical work, Dr. Appleyard also served as president of the Lancaster Medical Society and medical director of Lancaster General Hospital (1949 – 1957). 9

• Surgical specialization began to expand in the 1920s. Lancaster’s first orthopedic surgeon, Dr. J.T. Rugh, began treating orthopedic conditions and injuries in 1927.8 Dr. Ian Hodge was the first board-certified urologist to join the staff at Lancaster General Hospital in 1941.9

• Dr. Clarence R. Farmer was Chairman of the Department of Surgery from 1924-1939, and he was succeeded by Dr. Solomon Pontius as Chairman from 1939-1957. Dr. John Farmer succeeded Dr. Solomon Pontius as LGH’s Chief of Surgery and made surgical privileges contingent on board certification or eligibility.9 This limited the eligible surgeons to Drs. Davidson, Witmer, Pranckun and himself. In 1940, there were only four operating rooms,9 but by 1979 there were 17 new operating room suites.9

• Lancaster’s first board-certified cardiothoracic surgeon, Dr. Robert Witmer, came in 1949. In 1953 he performed a closed mitral commissurotomy, the first cardiovascular operation at LGH. From the late 1950s to 1971, Dr. Witmer supervised a residency rotation for senior surgical residents of the University of Pennsylvania.9

• Other specialty pioneers included Dr. Irvin Uhler, Lancaster’s first oral surgeon, in 1949,9 and Dr. John L. Polcyn, Lancaster’s first neurosurgeon, in 1960.9

• The growth of cardiology was led by Drs. John Esbenshade, Richard Mann, Dwayne Goldman, and William McCann.9 Medical and surgical critical care units were established in 1965.9 Drs. Esbenshade and Goldman performed the first cardiac catheterization in 1968, and Dr. Lawrence Bonchek performed the first open heart surgical operation in Lancaster County in September, 1983.9

• In 1987, Lancaster General Hospital received designation from the newly established Pennsylvania Trauma System Foundation.9 Dr. Frederick Beyer became the trauma center’s director from 1987 to 1997 13

These state-of-the-art programs set the standard for superior quality care throughout Lancaster and helped foster improvements throughout the health care system – notably in anesthesia, radiology, and emergency department services.

HISTORY OF LAPAROSCOPIC SURGERY

Laparoscopic cholecystectomy was first described in the Annals of Surgery in 1988, and by the early 1990s had become commonplace. Its implementation was unique in that it began in community hospitals rather than academic centers.

Robotic surgery, the next and most recent advance in minimally invasive surgery, has been enthusiastically adopted by urologists and gynecologists here in Lancaster and nationwide; general, bariatric, and colorectal surgeons have followed closely thereafter.

Robotic surgery is the latest innovation at the center of an ongoing debate regarding the adoption of expensive technology before it has been thoroughly evaluated. The current discussion echoes the earlier debate when laparoscopic surgery was introduced into general surgery.

Endovascular stenting is another spectacular technologic advance that allows intraluminal, minimally-invasive repairs to major arteries, including intrathoracic and intra-abdominal aneurysms and injuries.14 The new endovascular unit in the LGH operating suite allows state-of-the-art treatment through the collaboration of vascular surgeons, cardiac surgeons, radiologists, and cardiologists. It represents the latest example of the continuous improvement in surgical care in Lancaster County throughout its history.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Thank you to Nikitas J. Zervanos M.D., who encouraged me to research and write this article on the history of surgery in Lancaster County. I would also like to thank Christopher Marks, who assisted with research and editing while he was a student at Franklin and Marshall College.

REFERENCES

1. Gawande A. Two Hundred Years of Surgery. N Engl J Med. 2012; 366(18): 1716-1723. doi:10.1056/nejmra1202392

2. Rutkow IM. Surgery: An Illustrated History. St. Louis 1993. Mosby Year Book in collaboration with Norman Pub.

3. Ellis F, and Evans S. History of Lancaster County, Pennsylvania: With biographical sketches of many of its pioneers and prominent men. Originally published 1883. Penn State U. Digital Libraries. Identification# OCLC 4989804.

4. Eshleman S, and Wentz HS. (1995). Henry Carpenter, M.D. Our Medical Heritage: 1844 - 1994, 157-159. Retrieved May 31, 2019.

5. Bell TM. A Brief History of Bloodletting. J Lanc Gen Hosp. 2014 (11); 4:119-123.

6. Cargas C. The Benjamin Musser Home and Hospital (Unpublished dissertation). Penn State University. 1977.

7. Prizer E. 1995. The Ninetieth Year of the LC&CMS (H. T. Tindall M.D., Ed.). Our Medical Heritage: 1844 - 1994. Retrieved May 31, 2019.

8. Atlee WA. 1995. History of the Doctors Atlee (H. S. Wentz M.D. & J. Loose M.A., Eds.). Our Medical Heritage: 1844 - 1994. Retrieved May 31, 2019

9. Wentz HS. A History of Lancaster General Hospital in Celebration of its 100th Anniversary.

10. Wentz HS. (1995). D. Hayes Agnew, M.D. Our Medical Heritage: 1844 - 1994. Retrieved May 31, 2019.

11. Seigworth K. 2017. A Historical Overview of the Lancaster County Almshouse and Hospital (Unpublished dissertation). Millersville University.

12. Staff of LNP/Lancaster Online. Dec.11, 2018. History of St. Joseph Hospital in Lancaster: Bob Hope, the nuns and more. Retrieved May 31, 2019. https://lancasteronline.com/news/history-of-st-joseph-hospital-in-lancaster-bob-hope-the/article_0ce600e2-fd7e-11e8-a607-c3f72b1c80c4.html

13. Rogers FB, Beyer F, and Gross B. A Historical Perspective of the Level II Trauma Center at Lancaster General Hospital. J Lanc Gen Hosp. 2014; 9(4): 119-123. http://www.jlgh.org/Past-Issues/Volume-9---Issue-4/Historical-Perspective-on-the-Level-II-Trauma-Cent.aspx

14. Eagleton MJ, and Jonathan LS. “The Vascular Surgery Operating Room.”

Endovascular Today, Aug. 2007: pp 25-30.

https://evtoday.com/issues/2007-aug