Fall 2019 - Vol. 14, No. 3

Fall 2019 - Vol. 14, No. 3

How Healthy Is Your Weight Loss Advice?

Virginia M. Wray, D.O.

Penn Medicine Lancaster General Health Physicians

Healthy Weight Management and Bariatric Surgery

INTRODUCTION

The United States spends more than any other country for health care (about $3 trillion), but in 2014 it ranked only 43rd in life expectancy.

1 According to the 2010 Global Burden of Disease Study, the No. 1 risk factor for morbidity and mortality in the United States is poor diet, followed by obesity, smoking, and hypertension.

1 More than 70% of Americans are overweight (BMI 25-30) or obese (BMI >30), as determined by the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) for 2013-2014.

2 More detailed data from 2015-2016 reveals that about 40% of U.S. adults are obese, with an almost 20% incidence of obesity in the young, including adolescents.

3

Goals set almost a decade ago for Healthy People 2020 aimed to reduce the prevalence of obesity to 30.5% for adults and 14.5% for youth,

4 so we are obviously continuing to lose ground on this crucial public health issue.

In 2008 medical costs linked to obesity in the United States were estimated at $147 billion, and in 2012 the total estimated cost of diagnosed diabetes was $245 billion.

5 Meanwhile the weight loss industry is valued at over $66 billion and is thriving and growing.

6 It preys on the misery of individuals seeking weight loss, and muddies the waters of what we already know.

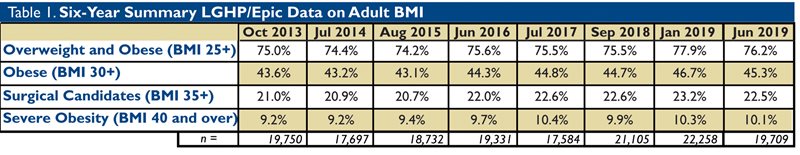

Here in Lancaster County and surrounding areas, the situation is no better. Data from the electronic health records of 19,709 individuals in 23 practices of Lancaster General Health Physicians reveal that fully 76% of individuals are overweight or obese, and a worrisome 45% have a BMI > 30. Furthermore, six-year summary data show no improvement despite system-wide efforts (Table 1).

7

Table 1. Data from the electronic health records of 19,709 individuals in 23 practices of Lancaster General Health Physicians show 76% are overweight.

Given the alarming disparity between our goals and reality, and the myriad of medical implications of excess bodyweight, we need to take a good look at the effectiveness of our approach in daily practice.

APPROACHING THE SUBJECT

We measure weight at most office visits, and when we see someone who is at risk because of excess weight, it would seem only logical that we should talk about it, in an attempt to reduce the risk to their health. While studies show that conversations about weight loss may help motivate changes in behavior,

8 the wrong approach can have the opposite effect.

Don’ts

• Don’t blame all their health issues on their weight. Sure, there may be a correlation, but you cannot prove cause and effect in the uncontrolled office setting and there are certainly other factors involved.

• Don’t ask them if they have ever considered losing weight. There is no switch to flip here. Most have tried and failed. Once the subject is on the table, it is often helpful to ask what their past weight loss attempts were like.

• Don’t tell them they should lose weight. They didn’t choose to be overweight. They may have made poor food choices or have difficulty exercising, but gaining lots of weight was not on their bucket list.Telling a patient to try to lose weight by their next visit is akin to telling a depressed patient to try to be in a better mood next time.

• Don’t use the medical terms obese and morbid obesity in your conversation with the patient, as many patients find these terms personally insulting. Classifications of BMI help us stratify risk, but remember that BMI is just a screening tool and has many limitations, including not accounting for age, gender, bone structure, muscle mass, loss of height, etc. No matter how high the BMI, referring to excess weight as simply “overweight” is truthful and seems to be much less offensive.

Hopefully, it goes without saying that the word “fat” should not be used as an adjective. I do not let my patients get away with describing themselves this way; no “F” word allowed. I ask them to please rephrase their sentence with “overweight,” because to call oneself “fat” is disrespectful to the majority of the body which is an amazing network of organ systems working together in phenomenal balance just to allow them to form words.

• Don’t tell them they are going to die relatively soon if they don’t do something about their weight. Whether it could be true or not, it is just not motivating for most people. Although scare tactics may occasionally get people into my weight management clinic, I have seen it cause a lot of anxiety, which becomes an obstacle.

• Don’t push the issue if you see they are not ready to talk about it. At the next visit, you don’t even have to mention weight or BMI. Instead, try asking more specific questions about their eating and drinking patterns, or how they are meeting or plan to meet their physical activity needs. We should be addressing healthy lifestyle habits regardless of weight.

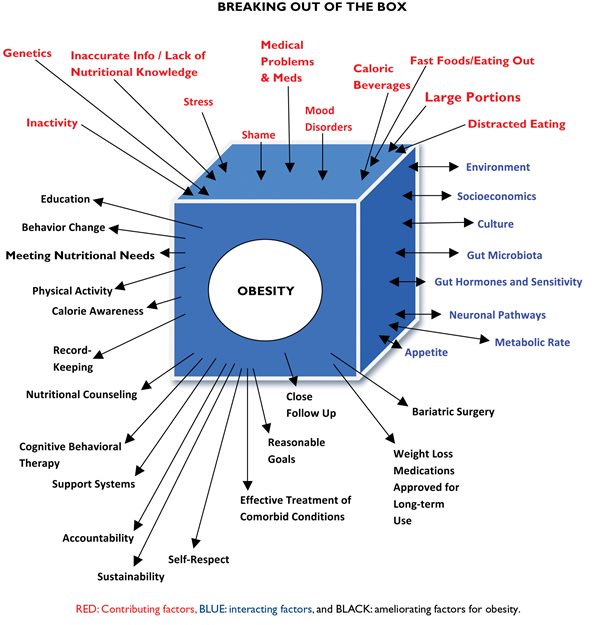

• Please don’t ever tell them to eat less and move more. This is a detrimental oversimplification that reveals a glaring misunderstanding of the complicated pathways leading to excessive weight gain. Many obese patients are undernourished, meaning they are not eating enough of the nutrients they need every day. In Fig. 1 you will see an abridged version of the complexity of interacting factors that we must understand to help overcome obstacles to weight loss.

Do’s

• Do be sure you have listened to their concerns and reasons for their visit before you address weight. Always be respectful and sensitive. They may be ready to be the first one to want to discuss their weight. If not, you could ask them if there is anything about their lifestyle that they think they should work on changing, to improve their health. Go for the low hanging fruit, like reducing sugary beverages. When they say, “yeah, I can do that,” then you know you have a good starting point to build on.

• If you intend to discuss weight, do always check the weights from the last several visits. It could be they have recently lost some weight, and it has been my experience that they like it when you notice. This could be a time to find out what they are doing differently and to encourage them to continue. A patient in our program who lost 30 pounds in five months came to her follow-up visit in tears because she had seen an unnamed specialist who not only didn’t notice her weight loss, but as usual told her she should lose weight.

• Do remember that while you are the health care expert, your patient is the expert on their own body experience. Your discussion should be a collaboration. Some weight loss resources will tell you that you should ask their permission to talk about their weight. I personally find that rather awkward. I might ask how they are feeling about the number on the scale today. Like CHF, overweight is a symptom of a larger problem. You might ask them how they are doing with caring for their basic physical needs, like how they are sleeping, how much water they are drinking, are they doing any intentional physical activity, or how many fruits and vegetables per day they are eating.

• Do acknowledge that weight loss is a very challenging process that usually requires a multidisciplinary approach (Fig. 1). The guidelines may be simple, but not so easy to implement, especially in a culture that is often nutritionally bankrupt. In addition, we are learning more and more about the big role of genetics in susceptibility to obesity, which may be why your patient’s skinny co-worker can eat whatever they want, while your patient “looks at food and gains weight.”

Fig. 1. An understanding of the complicated pathways that lead to excessive weight gain is essential in overcoming obstacles to weight loss.

CAN WEIGHT LOSS BE BAD FOR YOU?

(RISKS of WEIGHT LOSS)

Sarcopenia and Bone Loss

It is known that a portion of weight loss is typically muscle loss, and many researchers agree that one quarter of each pound lost is muscle.

9 Many commercial weight loss programs discourage exercise while on the program, knowing that the pounds will go down on the scale more quickly, and who doesn’t want that? Unfortunately, some of that loss is loss of muscle and other body components; when the weight is regained, as occurs in the vast majority of cases, it is regained as fat, not as muscle mass. Resting energy expenditure goes down and appetite goes up, and the end result is often worse than the starting weight.

Sarcopenia, i.e. age-related decline in muscle mass, strength, and function, becomes apparent at age 50. The loss of muscle mass is approximately 8% per decade from the age of 50 years until 70, after which it is commonly lost at a rate of 15% per decade.

10 The highest incidence of obesity in U.S. adults is in the 40-59 year age group.

3 As a result, many obese patients are seeking advice for weight loss at a time when they are most at risk not only for muscle loss, but also for loss of bone density.

We need to be aware that loss of weight in older adults can promote osteoporosis through its effects on bone metabolism and turnover. This phenomenon is seen especially after prolonged calorie-restricted diets.

9 These problems can be prevented by encouraging adequate lean protein throughout the day (0.8-1.2g per kg) and encouraging weight bearing and resistance exercises. Patients must be counseled that exercise can decrease the speed at which they lose weight because it preserves their muscle mass. In our society of quick fixes, it can be difficult to explain that slow and steady wins the race for healthy weight loss. I tell them they can lose weight without exercise, but they cannot be healthy without exercise. Intentional physical activity should be seen as a means to health, not necessarily a means to weight loss, although it is crucial to maintenance of weight loss.

Recidivism

Studies show that overweight people can lose weight on almost any diet. In a meta-analysis, Johnston et al compared 48 unique randomized trials including 7,286 individuals on various diet programs, and found significant weight loss with any low-carbohydrate or low-fat diet.

11 The problem was long-term adherence. Most studies consistently show that with good adherence weight loss is in the 5%-10% range at three months, but it wanes by six months and regresses by 12 months, mainly because of loss of adherence. The danger of weight loss and subsequent regain is not just loss of muscle mass, but also the risk of metabolic adaptation, with a decrease in resting energy expenditure. To make matters worse, weight loss can lead to increased appetite, contributing to the cascade of factors that cause the body to trend back to its previous weight set point and possibly beyond.

6

Diet Dangers

Not only can many diet programs be difficult to adhere to, but they may not be safe for everyone. For instance, the currently popular ketogenic diet can have many pitfalls, and should be closely monitored for medical complications, especially in people with diabetes or other health issues.

12 Patients should be monitored for fluid and electrolyte abnormalities including hypokalemia, hyperuricemia and gout, gallstones, gastrointestinal complications, QT interval prolongation, hypoglycemia with diabetes medications, elevated transaminases, and hypotension.

At LGHP Healthy Weight Management (HWM) we offer a physician-monitored ketogenic weight loss program using meal replacement for three months; participants are required to attend weekly classes, and have close follow-up that helps them acclimate to a lifelong healthy lifestyle program after they have completed the three months of accelerated weight loss. Classes address topics in nutrition, behavior change, and physical fitness.

Calorie-controlled diets are commonly used by health care professionals, but staying under a certain calorie level in no way ensures adequate nutritional intake of proteins and vegetables and fruits which are essential for normal metabolic function. The focus should not be so much on restriction as on meeting essential nutritional needs, which naturally leads to eating less of what they don’t need.

HOW TO GIVE SOUND NUTRITIONAL ADVICE

We have to wrestle daily with a dieting/weight loss industry that gives false and misleading information because there is money to be made from the obesity epidemic. Patients are usually unaware that most providers get very little training in nutrition. In a recent large survey of cardiologists, 95% reported they felt a personal duty to counsel their patients on nutrition, but 90% reported inadequate education about nutrition to do so.

13

You may not have had a lot of nutritional training, but your rigorous medical training means that you learn fast. You have access to healthy eating guidelines that are well-studied, evidence-based, and well-established. An excellent resource is

Dietary Guidelines for Americans 2015-2020 Eighth Edition. It is geared toward health professionals and policymakers and is grounded in the most current scientific evidence.

14 It downloads easily on your device and will make you a nutritional expert quickly.

We already know what the human body needs. While we are still unfolding the mysteries of why some people gain weight, we do know what to tell them to eat:

• We typically need three meals daily (otherwise we will not be able to meet our nutritional needs for daily tissue and organ system maintenance and repair).

• All meals need one half plate of any combination of vegetables and fruit (i.e. half our daily volume of food should come from fruits and vegetables), one quarter lean protein (size of one’s palm), and a fist size of complex carbohydrates such as a baked potato.

• It is not sound nutritional advice to tell patients not to eat complex carbohydrates (starches) as in the appropriate portions they are excellent fuel for our brain and muscles. We can live without the starch if we don’t want it, but a reasonable portion (up to one quarter plate) should not be withheld if desired, as over-restricting carbohydrates can eventually lead to snacking of processed carbohydrates of low nutritional value later in the day.

• A snack between meals should be utilized only if hungry, should contain a source of protein and a fruit or vegetable, and should be eaten without distraction.

For patients, the most evidence-based meal plan can be found at ChooseMyPlate.gov.

Regarding calories, awareness is key. If they are setting up their MyPlate at each meal, calories are generally not an issue, but they do need to read the nutrition facts on packaged foods and snacks and find calories on menus to see if they are reasonable. I tell my patients that food is bad if it makes you physically ill. Otherwise, sugary foods, desserts, high fat foods, alcohol, and other calorie-dense but nutritionally poor foods should be occasional and special, not a staple in the home. Restriction is generally not sustainable, but respect is something we can build on for life. Food logs are a well-known and well-documented tool for weight loss, as awareness is always the first step to change.

As mammals, we are by nature water drinkers and need to be hydrating throughout the day. Diet beverages can be useful to transition off sugary beverages, with the eventual goal to get them transitioned to mostly pure water (or water with lemon, or infused with herbs or other fresh fruits or vegetables). If patients are just starting to transition to water, I ask them to make every other beverage pure water.

Counseling about physical activity is a critical part of any health management program, with comprehensive, multisystem benefits.

15 Regardless of weight, we just need it. My goal for my patients who are not at goal is to do more this month than they did last month.

Fig. 2. Four Vital Signs for Metabolism help identify changes patients consider to be doable. The key is to make progress. Close follow-up is extremely helpful.

Fig. 2 is a summary of what I call four vital signs for metabolism. I address all four at each visit but you may only have time to address one and then work on changes the patient feels are doable. The key is to make progress, for which close follow-up is extremely helpful. A weekly or biweekly weight and food log check with the nurse or medical assistant can be helpful for reinforcement between visits. Patients need to be reminded that contrary to the ads they see on TV, an expected rate of healthy weight loss is about one pound per week, so they need to adjust to a long-term investment rather than a quick fix. The good news with meeting their self-care needs is that they will start feeling better even before they lose a lot of weight, and feeling better is usually the reason they want to lose weight in the first place.

SERVICES OF A COMPREHENSIVE WEIGHT MANAGEMENT CENTER

On June 19, 2013, the American Medical Association classified obesity as a disease requiring a range of medical interventions. It is a complex problem and a multidisciplinary approach works best. At our LGHP Healthy Weight Management center, we have a comprehensive approach starting with a full evaluation by one of our bariatric medicine providers.

A bariatric physician specializes in medical weight management, and typically is board certified in a primary care discipline as well as obesity medicine.

Once a medical evaluation is completed, an individualized plan is formulated. Close follow-up is arranged where food logs are reviewed, and ongoing progress is monitored and guided towards a sustainable plan. Registered dietitians are utilized for nutritional counseling.

We have several exercise physiologists on staff in our onsite fitness center. They meet patients where they are with activity, and help them identify their goals and build a comprehensive exercise program that they can later take to their home or community once they feel confident. Participants are often pleasantly surprised how much more they can do physically when they engage themselves and build slowly over time. We also have a referral base of behavioral health professionals to work closely with disordered eating using Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT), which is therapy focused on changing future behavior using existing supports, rather than overly focusing on past experiences. Mood disorders commonly coexist with overweight, making counseling even more vital.

Weight loss medications are utilized when appropriate. These are preferably approved long-term agents, as short-term stimulants have a high rate of rebound weight regain. Our best results with weight loss medications are 5%-10% weight loss at one year,

16 so they are simply adjuncts and do not replace long-term behavior changes.

For BMI of 40 or more, or 35 with comorbidities such as diabetes, sleep apnea, and resistant hypertension, bariatric surgery can be an excellent option that generally achieves a larger weight loss and more amelioration of medical problems than other modalities, and continues to be underutilized. At LHGP Healthy Weight Management and Bariatric Surgery, our surgeons are experienced in minimally invasive bariatric surgery, and offer seminars and consultations to help individuals further explore if bariatric surgery is right for them.

Before a patient can undergo bariatric surgery, they must complete a comprehensive program of lifestyle changes led by our team of registered dietitians, exercise physiologists, and behavior health specialists, spanning a time frame of three to six months or more, depending on the patient's individual needs.

Most primary care and even specialty providers are not allotted the time needed to provide counseling on nutrition and behavior change, so referral to a comprehensive center like LGHP Healthy Weight Management and Bariatric Surgery can be appropriate. Ongoing communication is important, so progress toward goals can be reinforced at PCP office visits as well. These goals are about healthy behavior that promotes weight loss, rather than providing specific weight loss numbers. No one can control the rate the body releases the fat it stored during times of stress. Patients should be directed towards good self-care regardless of weight.

CONCLUDING EXHORTATION

With all the discouraging news about obesity in our nation, we need to strengthen our position on the positives. Studies show that even a modest weight loss of 5% can have significant health benefits.

17 However, it needs to be maintained, so the key is to focus not so much on the weight loss, but on the behaviors that promote health and how to incorporate them into a permanent lifestyle change. It is our job as clinicians to give our patients the most evidence-based, truthful information, and not to get distracted by fad diets that are not sustainable.

Recidivism is a reality, but success is as well. The National Weight Loss Registry is a database of more than 10,000 individuals who have succeeded in losing weight and keeping it off. Weight losses have ranged from 30 to 300 pounds, with an average loss of 66 pounds at 5.5 years. Ninety-eight percent of Registry participants reported they modified their food intake and 94% increased their physical activity, with 90% exercising an average of one hour per day.

18 Other common threads included eating breakfast, a weekly weight measurement, and low screen time.

I have found that the best foundation for an individual’s healthy weight loss program is cultivation of an attitude of respect and value towards themselves. It is a simple truth that we take care of what we value. Guilt and shame are not motivating, and are obstacles to success. Over-restriction is not sustainable. When individuals begin to address their basic physical needs, speaking with kindness towards themselves, and congratulating progress rather than expecting strict adherence, then they start to feel better, which cannot be measured on the scale. When they realize that no matter what they weigh they deserve good care, especially from themselves, they are on the path to success in achieving and maintaining a healthier weight.

REFERENCES

1. Mokdad AH, et al. The State of US Health, 1990-2016: Burden of diseases, injuries, and risk factors among US states.

JAMA. 2018; 319(14): 1444–1472. EBSCOhost. doi:10.1001/jama.2018.0158.

2. Fryar CD, Carroll MD, Ogden CL. Prevalence of overweight, obesity, and extreme obesity among adults aged 20 and over: United States, 1960–1962 through 2013–2014. National Center for Health Statistics. July 2016. Available from:

https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/products/hestats.htm

3. Hales CM, Carroll MD, Fryar CD, et al. Prevalence of obesity among adults and youth: United States, 2015–2016. NCHS data brief, no 288. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics. 2017.

4. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. Healthy people 2020 topics & objectives: nutrition and weight status. Available from:

https://www.healthypeople. gov/2020/topics-objectives/topic/nutrition-and-weight-status.

5. Burwell SM, Vilsack TJ. Message from the secretaries. 2015-2020 dietary guidelines for Americans — Page vii. Available from

https://health.gov/dietaryguidelines/2015/guidelines/message.

6. Dayan PH. A new clinical perspective: treating obesity with nutritional coaching versus energy-restricted diets.

Nutrition. 2019; 60(4): 147-151. doi:10.1016/j.nut.2018.09.027.

7. Distribution of BMI ranges by Practice. Lanc Gen Health Physicians/EPIC data. July 2019.

8. National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. Talking with patients about weight loss: tips for primary care providers. Accessed July 2019. Available from:

https://www.niddk.nih.gov/health-information/weight-management/talking-adult-patients-tips-primary-care-clinicians

9. Batsis, John A, and Alexandra B Zagaria. Addressing Obesity in Aging Patients.

The Medical Clinics of North America vol. 102,1 (2018): 65-85. doi:10.1016/j.mcna.2017.08.007

10. Yu, Solomon C Y et al. Clinical screening tools for sarcopenia and its management.

Current gerontology and geriatrics research vol. 2016 (2016): 5978523. doi:10.1155/2016/5978523

11. Johnston BC, Kanters S, Bandayrel K, et al. Comparison of weight loss among named diet programs in overweight and obese adults: A meta-analysis.

JAMA. 2014;312(9):923–933. doi:10.1001/jama.2014.10397

12. Abbasi J. Interest in the ketogenic diet grows for weight loss and type 2 diabetes.

JAMA. 2018;319(3):215–217. doi:10.1001/jama.2017.20639

13. Devries S, Willett W, Bonow RO. Nutrition education in medical school, residency training, and practice.

JAMA. 2019; 321(14):1351–1352.Published online March 21, doi:10.1001/jama.2019.1581

14. Dietary Guidelines For Americans 2015-2020 Eighth Edition. Available at

https://health.gov/dietaryguidelines/2015/guidelines/

15. Berra K, Rippe J, Manson JE. Making physical activity counseling a priority in clinical practice: the time for action is now.

JAMA. 2015;314(24):2617–2618. doi:10.1001/jama.2015.16244

16. Khera R, Murad MH, Chandar AK, et al. Association of pharmacological treatments for obesity with weight loss and adverse events: a systematic review and meta-analysis.

JAMA. 2016;315(22):2424–2434. doi:10.1001/jama.2016.7602

17. Magkos F, Fraterrigo G, Yoshino J, et al. Effects of moderate and subsequent progressive weight loss on metabolic function and adipose tissue biology in humans with obesity.

Cell Metabolism. 2016;23(4):591–601.

18. The National Weight Control Registry. Available at

http://www.nwcr.ws