Summer 2019 - Vol. 14, No. 2

Non-Operative Management of Epicondylitis

Moreno Payne Wennell

Patrick Moreno, MD CAQSM, RMSK

Penn Medicine Lancaster General Health Physicians Sports Medicine

Jennifer Payne, MD CAQSM

Penn Medicine Lancaster General Health Physicians Sports Medicine

Ryan Wennell, MD CAQSM

Penn Medicine Lancaster General Health Physicians Sports Medicine

INTRODUCTION / EPIDEMIOLOGY

Approximately 10 percent of the average family physician’s patients initially present with a musculoskeletal complaint, and “tennis elbow” is a common example. This term is used to describe pain over the lateral epicondyle at the site of attachment of the elbow’s extensor muscle(s) complex. (Fig. 1)

Fig. 1. Epicondylitis, or “tennis elbow,” is pain where the extensor muscles attach to the lateral epicondyle.

About 1%-3% of the population will suffer from this ailment annually, and it may take 12-15 months to resolve on its own. Since the vast majority of patients develop the problem as a result of overuse from work, rather than from recreational activity, this condition often is more than a nuisance and presents a serious physical and financial challenge for the patient/athlete. Interestingly, only about 5%-10% of tennis players develop this condition.

1

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

There are various theories about the pathophysiology involved. In certain scenarios, pain is due to inflammatory changes in this area (tendinitis), while in other circumstances, pain is due to structural changes in the tendon (tendinopathy). Distinguishing between tendinitis and tendinopathy remains a diagnostic challenge for the clinician. History can be helpful; a shorter duration of symptoms (weeks) favors an inflammatory process, and a longer duration (months) suggests tendinopathy.

Point of care ultrasound has greatly aided our ability to accurately diagnose tendinitis or tendinosis. This increase in the accuracy of diagnoses has brought advances in the timely delivery of non-surgical treatment options.

TREATMENT OPTIONS

Steroid Injection

At one time this condition was thought to be only due to inflammation at the lateral epicondyle, so it was treated with cortisone injections. It is now recognized that though cortisone injections may provide short-term pain relief, follow-up at one year reveals they are inferior to watchful waiting or physical therapy.

2,3

Physical Therapy

For acute episodes of epicondylitis in which tendon inflammation is the primary pathology, initial management, in addition to steroid injections, often consists of activity modification, counter-force bracing, NSAIDs, and ice massage.

For epicondylosis, where there is a change in tendon structure, management options begin with physical therapy and bracing of the wrist or elbow. Physical therapy is aimed at mobilizing tendon fibrils and stimulating tenocyte activation to achieve repair. Commonly, this approach includes eccentric exercises and manual therapy.

4

Nitroglycerin Patches

Nitrous oxide plays a role in modulating the inflammatory cascade, and it can result in tenocyte activation for tissue repair.

5,6,7 There is thus good evidence to support the use of nitroglycerin patches in the treatment of epicondylosis. Patches are readily available at low cost. When they are successful, pain can improve within two weeks, and structural change of the tendon can occur within six weeks. Since nitroglycerin causes vasodilation and may provoke a headache, gradual titration is warranted when initiating treatment. It is important to assess patients for relative contraindications such as severe migraine headaches, hypotension, menorrhagia, and concomitant use of phosphodiesterase inhibitors.

However, over a 12-month period, treatment with nitroglycerin does not demonstrate improved outcomes compared with expectant management, in part because most cases of epicondylitis resolve within two years.

8

PLATELET RICH PLASMA (PRP)

Platelet rich plasma (PRP) has gained popularity in recent years as a treatment for lateral epicondylosis. The benefit of PRP is theorized to be multi-factorial. Some credit local hemostatic action, while others think there is an element of soft tissue regeneration.

9 Other proposed mechanisms implicate the generation of an inflammatory cascade that occurs post injection.

10

As discussed earlier, steroid injections have been shown to have their greatest effect immediately after treatment, with decreasing efficacy as time passes.

11 PRP shows promise because the decrease in pain scores lasts longer than after steroid injections.

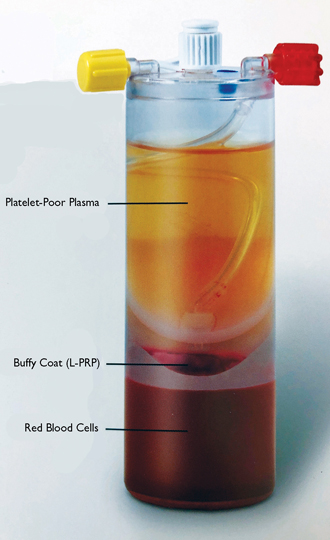

The process of extracting autologous PRP involves spinning blood drawn from the patient to separate its contents by weight. The platelet rich layer is extracted and refined to be injected into the tendon, a process that is usually done under ultrasound guidance. Therapy is often used post procedure. (Fig 2)

Fig. 2.Platelet Rich Plasma before (left) and after (right) processing. (Proprietary images.).

TENEX PERCUTANEOUS TENOTOMY

In some cases of recalcitrant lateral epicondylosis, it might be necessary to utilize a percutaneous needle tenotomy called TENEX to debride the extensor radialis carpus brevis (ECRB). In this procedure, a small incision is made in the skin and an ultrasonic probe in inserted into the incision. By hovering over the diseased tissue, ultrasonic waves help to debride the common extensor tendon.

Recent literature supports the use of this procedure as an alternative to surgical release of the common extensor tendon.

12 Studies have shown promising improvements in pain scores, function, and quality of life,

13 with complication rates similar to open and arthroscopic release of the common extensor tendon.

14

This procedure can be done in the convenience of the outpatient setting, with patients typically returning to their full function within six to eight weeks.

DISCUSSION

In summary, there are many nonsurgical options available for the patient afflicted with lateral epicondylosis. As our medical community has moved away from using corticosteroid injections as the mainstay of treatment for lateral epicondylosis, we have welcomed a new era in which point-of-care ultrasound guides our therapeutic treatments.

Research is ongoing regarding the best treatment techniques, in particular regarding PRP and percutaneous tenotomy. Currently, many insurances cover the percutaneous tenotomy approach for recalcitrant tendinopathy, but PRP is rarely covered and comes with an out-of-pocket cost. In the future, the hope is that these unique procedures will be covered by insurance carriers.

REFERENCES

1. Kane S, Lynch J, Taylor J. Evaluation of elbow pain in adults.

Am Fam Physician. 2014; 89(8): 649-657.

2. Johnson G, Cadwallader K, Scheffel S, et al. Treatment of lateral epicondylitis.

Am Fam Physician. 2007; 76(6): 843-848.

3. Foster Z, Voss T, Hatch J, et al. Corticosteroid injections for common musculoskeletal conditions.

AAFP Journal. 2015; 92(8): 694-699.

4. Cullinane F, Boocock MG, Trevelyan FC. Is eccentric exercise an effective treatment for lateral epicondylitis? A systematic review.

Clin Rehab. 2014; 28(1) 3–19.

5. McCallum SD, Paoloni JA, Murrell GA. Five-year prospective comparison study of topical glyceryl trinitrate treatment of chronic lateral epicondylosis at the elbow.

Brit J Sports Med 2011;45:416-420.

6. Paoloni JA, Murrell GAC, Burch RM, et al. Randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial of a new topical glyceryl trinitrate patch for chronic lateral epicondylosis.

Brit J Sports Med. 2009; 43: 299-302.

7. Bokhari AR, Murrell GA. The role of nitric oxide in tendon healing.

J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2012; 21(2): 238-44. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2011.11.001.

8. Sayegh ET, Strauch RJ. Does nonsurgical treatment improve longitudinal outcomes of lateral epicondylitis over no treatment? A meta-analysis.

Clin Ortho Relat Res. 2015; 473(3): 1093-1107.

9. Thanasas C, Papadimitriou G, Charalambidis C, et al. Platelet rich plasma versus autologous whole blood for the treatment of chronic lateral elbow epicondylitis.

Am J Sports Med. 2011;39(10);2130-2134.

10. Wong Sm, Hui ACF, Tong P, et al. Treatment of lateral epicondylitis with botulinum toxin: a randomized double blind, placebo controlled trial.

Ann Intern Med. 2005;143(11):793-797.

11. Walker-Bone K, Palmer KT, Reading IC, et al. Occupation and epicondylitis: a population-based study.

Rheumatology (Oxf). 2012; 51(2): 305-310.

12. Mattie R, Wong J, McCormick Z, et al. Percutaneous needle tenotomy for the treatment of lateral epicondylitis: a systematic review of the literature.

PMR J. 2017; 9(6):603-611.

13. Boden AL, Scott MT, Dalwadi PP, et al. Platelet-rich plasma versus TENEX in the treatment of medial and lateral epicondylitis.

J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2019; 28(1):112-119.

14. Riff A, Saltzman B, Cvetanovich G, et al. Open vs Percutaneous vs Arthroscopic surgical treatment of lateral epicondylitis: an updated systematic review.

Am J Orth. 2018;47(6). DOI:10.12788/ajo.2018.0043