Fall 2018 - Vol. 13, No. 3

How Does Integrating Behavioral Health

into Primary Care Practices Affect Utilization of Services?

Tracey Lavallias, DBA, MBA, M.Ed.

Executive Director, Behavioral Health Services

Penn Medicine Lancaster General Health

ABSTRACT

This study explored the relationship between Primary Care Behavioral Health (PCBH) and utilization of services among physician practices at Penn Medicine Lancaster General Health. Data were collected from 395 patient data sets for a quantitative cross-sectional study.

The analysis revealed that patients who received PCBH had fewer emergency department and professional visits.

INTRODUCTION

The U.S. health care system is not adequately meeting the needs of the 12 million adults who have both a medical condition and a behavioral health disorder.

1 These are the sickest adults, and this deficiency raises costs. Salzberg and co-workers found that over a two-year period, 34% of adults with a behavioral health condition were in the 90th percentile for health care spending, compared with fewer than 25% of those without a behavioral health condition.

Fortunately, within the last 20 years Primary Care Behavioral Health (PCBH) has gained momentum in meeting not only the behavioral health needs of patients receiving primary care, but also their overall health care needs.

2 Hunter and co-workers defined PCBH as a way to bring the skills and expertise of behavioral health providers to the setting in which patients are already receiving care. Montano and co-workers found that the success of PCBH is dependent on a variety of factors, including the setting as well as the patient population.

3 They believed this was true because most systems of care rely on traditional mental health interventions, which do not work in a PCBH model. Rather, to be effective in a PCBH model, the provider of behavioral health must be readily accessible within the practice, because time demands, and practice expectations, are structured uniquely in a primary care physician practice.

In a PCBH model, the behavioral health provider and Primary Care Physician (PCP) work together in a shared system. The behavioral health provider functions as a member of the primary care team to address the full spectrum of problems that the patient brings to the PCP. With this model there is one treatment plan targeting the patient’s needs and a shared medical record, all of which makes the patient likely to perceive behavioral health as a part of his or her medical care.

4

BACKGROUND/CONTEXT OF THE PROBLEM AT LGH

In 2011, physicians within Lancaster General Health Physicians (LGHP) practices expressed concern that the growing number of patients who required behavioral health services was a challenge to their practices. Consequently, in June 2012, LGH engaged a consulting firm to determine the scope and breadth of this problem, to provide an analysis of opportunities for outpatient behavioral health services, and to recommend revisions to the existing Strategic Business Plan for Behavioral Health Services.

The consultants reviewed internal and external data consisting of utilization review reports, internal business intelligence, community focus groups, and a summary of needs that had been expressed not only by the primary care physicians, but also other service lines, including Cardiology, Oncology, Orthopedics, and Women and Babies.

Based upon their analysis of this information, the consultants highlighted the following concerns:

1) An increase in behavioral health appointments at the primary care sites;

2) An inability to manage behavioral health crises in the PCP’s office;

3) Because of the above, primary care patients were presenting at the medical center’s Behavioral Health Emergency Department (BHE).

The consultants recommended an integrated behavioral health approach within primary care, which was subsequently developed.

RESEARCH QUESTION

To better understand the effect of PCBH on health care costs, the author sought to answer the following question:

“How does integrating behavioral health care into primary care practices affect the utilization of services?"

METHODS

The utilization of services by PCBH patients in the Lancaster General Health system was studied for the four categories of care associated with the highest cost:

1.

Emergency department visits were analyzed for utilization and volume by PCBH patients that resulted in an emergency department admission.

2-4.

Inpatient admissions, outpatient encounters (e.g. laboratory testing), and professional visits (e.g. office visits) were analyzed for utilization volumes and costs before and after PCBH interventions.

RESULTS

Demographic Information

There were 395 unique patient visits during this evaluation period (Table 1); 56% of patients had <2 visits; 26% had 2-5 visits; and 16% had >5 visits.

Three Licensed Clinical Social Workers (LCSWs) with varying levels of experience provided brief behavioral health interventions for patients referred by primary care physicians. Their caseloads varied from 97 to 160 each, as noted in Table 1.

The providers all saw patients with varying levels of risk, as determined by LGH’s Risk Assessment Measure (RAM). This assessment tool measures disease, social and behavioral factors, and utilization, and is administered annually to all patients receiving care at primary care practices.

Table 1 indicates that the overwhelming majority (73%) of patients receiving PCBH interventions were in the low-risk category. Clarke and co-workers suggested that to achieve the greatest impact on cost reduction, integrated care initiatives should focus on the large number of low risk patients.

5 Less-common patients in the medium and high-risk categories may not fully benefit from PCBH interventions.

Table 1 also indicates the frequency of medical co-morbidities in patients who received PCBH interventions: 36% had hypertension, 13% had diabetes, and 7% had chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. These associated conditions are relevant because Ngo and co-workers reviewed evidence that mental illness increases the chance that an individual will also suffer from one or more chronic illnesses.

6 They also indicated that mental health conditions make patients less likely to seek help for symptoms or to adhere to treatment. PCBH is designed to address these barriers.

OUTCOMES

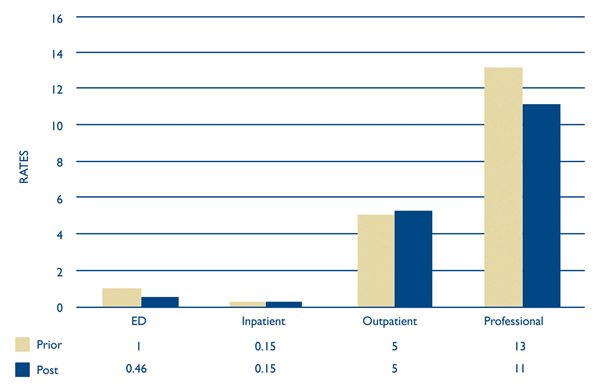

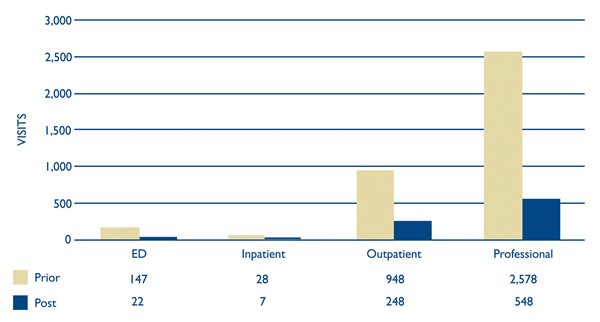

Emergency department utilization decreased by more than half for patients who received PCBH during the time period of this study (Figs. 1 and 2).

Fig. 1. PCBH utilization by rate (events/patient), before and after PCBH. (ED) Emergency Department=Outpatients with ED Admission of Emergency/Trauma, Inpatient=Inpatient Admission, Outpatient=Outpatient Patient without ED Admission, and Professional=Professional Patient Encounters for Primary Care Office Visits or related to Inpatient/Outpatient.

Fig. 2. PCBH utilization by volume (total number of events). (ED) Emergency Department=Outpatients with ED Admission of Emergency/Trauma, Inpatient=Inpatient Admission, Outpatient=Outpatient Patient without ED Admission, and Professional=Professional Patient Encounters for Primary Care Office Visits or related to Inpatient/Outpatient.

This reduction in emergency department utilization resulted in lower cost per encounter, as indicated by the medical billing codes. Krupski and co-workers also found that integrated care reduced emergency room visits, enhanced health status, and improved retention in treatment.

7 Concurrently, Collins and co-workers found that PCBH reduced the utilization and costs of emergency department treatment,

8 with a reduction in the proportion of clients admitted via the emergency department. Consistent with the research of Clarke and co-workers,

5 as well as Krupski, the present study indicates that the reduction in emergency department utilization and costs is directly related to the PCBH intervention.

This finding was mirrored by the findings for utilization and cost of professional visits (Fig. 2). They decreased from a rate of 13 visits per patient to 11, with a reduced cost per episode, per patient. This rate of reduction is consistent with other studies among larger and more diverse patient groups that found greater use of professional visits among high need adults – defined as those with three or more chronic medical conditions – who also have a diagnosed behavioral health condition.

9 These patients’ high utilization rates are also more likely to persist over time. In contrast, integrated care reduced the utilization of professional visits and the associated costs. A similar study that used health plan accounting records found that over a period of 24 months, patients who had integrated care interventions had lower mean professional visit costs per patient compared with control patients.

10

The results of the current study at LGH are encouraging, but they are not consistent in all cost categories, as the rates of inpatient and outpatient utilization remained flat during this study period. However, co-investigators indicated that the study’s period might have been too short to capture the effect of PCBH in those two categories; and that longer data collection is necessary to determine the true effect, due to the seasonality of costs. A more comprehensive study found that integrated care was associated with significantly lower inpatient costs but higher outpatient costs, so that the reduction in total costs was not significant.

7 Additionally, van Mierlo et al.

11, found integrated care saves enough money to pay for itself, so that even when behavioral health care is added to traditional medical care, there is no increase in overall yearly costs.

FINDINGS

The evidence related to emergency department and professional visits supports the conclusion that Primary Care Behavioral Health results in a reduction in the utilization of services at LGH primary care practices, thereby reducing costs. Although more data are necessary for these results to be generalizable across all LGH primary care practice settings, it is particularly encouraging. This finding is consistent with other studies that utilized larger sample sizes and study periods, which supports prolonging the present study to account for the seasonal variability within LGH physician practices.

CONCLUSIONS

It should be axiomatic that primary care is essential for treating individuals with mental illness, since they often experience higher rates of morbidity and lower life expectancies than the general population. A policy brief by the Kennedy Forum emphasized the importance of PCBH in addressing the mental health needs of patients.

12 The report stressed that “fully integrated behavioral health care models (e.g. PCBH) are beneficial for common mental health conditions, resulting in improved clinical outcomes, increased access and satisfaction, and reduced overall health care costs.” This study at LGH confirms the conclusions of the Kennedy Forum report by demonstrating that PCBH reduces the utilization rates of primary care patients who receive PCBH. As LGH moves further to improve the population health of patients in the primary care setting, PCBH will become an increasingly important part of that initiative.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I would like to acknowledge Caroline Barnhart and Heather Hostetter for their contributions in data gathering and analysis.

This research study was conducted without appropriate prospective IRB approval.

REFERENCES

1. Salzberg CA, Hayes SL, McCarthy D, et al. Health System Performance for the High-Need Patient: A Look at Access to Care and Patient Care Experiences. Issue brief (Commonwealth Fund). 2016; 27: 1.

2. Hunter C, Goodie J, Oordt M, et al. Integrated Behavioral Health in Primary Care 2014 (4th ed.). Washington, DC. American Psychological Association

3. Montano DE, Kasprzyk D, Glanz K, et al. (2008). Theory of reasoned action, theory of planned behavior, and the integrated behavioral model.

4. Whitlock EP, Orleans CT, Pender N, et al. Evaluating primary care behavioral counseling interventions: An evidence-based approach. Am J Prev Med. 2002; 22: 267-284.

5. Clarke RM, Jeffrey J, Grossman M, et al. Delivering on accountable care: lessons from a behavioral health program to improve access and outcomes. Health Affairs. 2016; 35(8): 1487-1493.

6. Ngo VK, Rubinstein A, Ganju V, et al. Grand challenges: integrating mental health care into the non-communicable disease agenda. PLoS Med; 2013: 10(5), e1001443.

7. Krupski A, West II, Scharf DM, et al. Integrating primary care into community mental health centers: impact on utilization and costs of health care. Psych Serv. 2016; 67(11): 1233-1239.

8. Collins C, Hewson D, Munger R, et al. Evolving Models of Behavioral Health Integration in Primary Care (New York: Milbank Memorial Fund, 2010). New York, NY.

9. Hayes S, Salzberg C, McCarthy D, et al. High-Need, High-Cost Patients: Who Are They and How Do They Use Health Care? New York, NY: The Commonwealth Fund. 2016

10. Reiss-Brennan D, Brunisholz K, Dredge C, et al. Association of integrated team-based care with health care quality, Utilization and Cost. JAMA. 2016; 316(8): 826-834.

11. van Mierlo LD, MacNeil-Vroomen J, Meiland FJ, et al. Implementation and (cost-) effectiveness of case management for people with dementia and their informal caregivers: Results of the COMPAS study. Tijdschrift Voor Gerontologie En Geriatrie 2016; 47(6): 223.

12. Fortney J, Sladek R, and Unutzer J. Fixing mental health care in America: a national call for integrating and coordinating specialty behavioral health care into the medical system. In An Issue Brief Released by the Kennedy Forum: The Kennedy Forum and Advancing Integrated Mental Health Solutions Center. 2014.