Summer 2018 - Vol. 13, No. 2

Bingaman DiCamillo

Bingaman DiCamillo

PHOTO QUIZ FROM THE EMERGENCY DEPARTMENT

'I Swallowed a Lock'

Luke Bingaman, MPAS, PA-C

Vito DiCamillo, M.D.

Lancaster General Health Physicians/Penn Medicine Urgent Care

Editor’s Note: This interesting case is labeled a Photo Quiz because though the diagnosis seems self-evident, there is much more here than meets the eye.

CASE HISTORY

A 15-year-old male presented to urgent care three days after swallowing a small brass luggage lock. The patient was packing when he placed the lock in his mouth and accidentally swallowed it. His pediatrician saw him on the day this occurred, and ordered an X-ray of the neck, chest, and abdomen. At that time, the lock was thought to be in the stomach. The pediatrician prescribed polyethylene glycol, and advised repeat imaging in approximately three days.

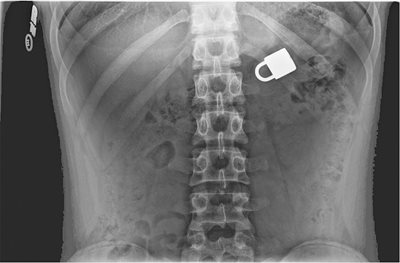

The patient now presents to urgent care three days later, noting normal bowel function and no abdominal pain, hematochezia, or fevers. Repeat X-ray of the abdomen was ordered (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1: Anteroposterior view of the abdomen.

QUESTIONS

1) Where is the lock located?

2) Where is it most likely to hang up?

3) What is the appropriate treatment approach in this patient?

4) In which cases should emergency endoscopy be performed?

5) When is observation sufficient?

6) Which swallowed objects might not be seen on X-ray?

ANSWERS

1) Likely within the stomach or a bowel loop

2) Pyloric sphincter

3) Serial radiographs and observation. If the object fails to progress, refer to gastroenterology for endoscopic removal.

1

4) Swallowed button batteries; sharp objects in the esophagus; ingested multiple magnets; signs of airway compromise; evidence of esophageal obstruction; fever; abdominal pain; vomiting; or an object still in the esophagus more than 24 hours after ingestion.

1,2

5) Asymptomatic and non-hazardous foreign body (FB) in esophagus <24 hours, or below the diaphragm.

1,3

6) Wood, plastic, glass, fish or chicken bones.

2

DISCUSSION

Foreign body ingestion in children is a common presentation in the urgent care setting. When possible, it is helpful to know what was ingested, as this will determine the treatment approach.

Coins are the most common foreign body ingested by children.

1,3 During the history and physical exam, it is important to look for evidence of upper airway obstruction, bowel obstruction, or perforation. Such signs and symptoms would include coughing, wheezing, vomiting, subcutaneous emphysema, melena, abdominal pain, or abnormal bowel sounds.

3 As the pediatrician did in the above case, begin by checking radiographs of the neck, chest, and abdomen (anteroposterior and lateral).

If the foreign body is in the stomach, it is typically asymptomatic unless it is causing gastric outlet obstruction.

1 If it is in the esophagus, it is more likely to cause symptoms such as vomiting, drooling, dysphasia, pain, or a FB sensation.

3 If it is past the proximal duodenum, and there are no complicating hazardous circumstances, the patient can be monitored with serial radiographs every three to four days (two days with button batteries).

Most of these foreign bodies will pass without complications.

1,3 If radiographs are negative and there is a concern for ingestion of a radiolucent object such as a toy or bone, consider Computerized Tomography (CT), Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI), or a swallow study.

1

If the parents are certain about the type of foreign body that was ingested, the patient is asymptomatic, and the object has benign characteristics, no advanced imaging is indicated and it is reasonable to simply observe.

In the case presented here, the lock was unable to move beyond the pylorus, and the patient underwent upper endoscopy with successful removal of the lock, 12 days after ingestion.

REFERENCES

1. Gilger MA, Jain AK, and McOmber ME. Foreign bodies of the esophagus and gastrointestinal tract in children. Retrieved November 28, 2017, from

https://www.uptodate.com/contents/foreign-bodies-of-the-esophagus-and-gastrointestinal-tract-in-children.

2. Uyemura MC. Foreign Body Ingestion in Children.

Am Fam Physician. 2005 (Jul 15);72(2):287-291.

3. Buttaravoli P, Leffler SM,

Minor Emergencies. (3rd ed.) 2012. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders.