|

|

|

Spring 2018 - Vol. 13, No. 1

100 Years Later: The World War I Army Field Diary

of Lancaster Ophthalmologist Dr. Harry Culbertson Fulton

Peter C. Wever, M.D., Ph.D.

Clinical Microbiologist, Jeroen Bosch Hospital, 's-Hertogenbosch, The Netherlands

Editor’s Note: In early 2017 Dr. Peter C. Wever of The Netherlands contacted us to inquire about publishing the following article in the Journal. He had acquired, in June 2011 on eBay, a diary titled “Diary/Case Book H.C. Fulton, Evacuation Hospital #7, A.E.F (American Expeditionary Forces).” He was able to identify H.C. Fulton as Dr. Harry Culbertson Fulton (1885-1989), who became Lancaster’s first full-time board-certified ophthalmologist in 1930, and practiced here until retiring in 1974 at the age of 88. Drs. Paul Ripple and John Bowman discussed Dr. Fulton in a 2012 article published in this Journal.1

Dr. Wever developed the following narrative from Dr. Fulton’s diary, and from a letter (Text Box 1), which reveals Dr. Fulton to be an insightful and contemplative eyewitness to the earth-shattering events he was a part of. Amid the engulfing carnage and his repeated relocations, Dr. Fulton was able, somehow, to reflect on what he saw in literate, sensitive, and philosophical terms.

One cannot help wondering if his bloody wartime experiences led to his post-war choice of ophthalmology, arguably the least bloody and most delicate of the surgical specialties.

INTRODUCTION

The “Diary/Case Book H.C. Fulton, Evacuation Hospital #7, A.E.F,” dated September 1918, has 19 handwritten pages including the title page, and contains the names of 69 patients cared for by Dr. Fulton, with short descriptions of their ailments and treatments.

THE PRE-WAR YEARS

Harry Culbertson Fulton was born on September 26, 1885, at Lower Chanceford Township, York County, Pennsylvania, the son of James Culbertson and Sallie Mitchell Fulton. 2 Inspired by an uncle who was a country doctor, he pursued a career in medicine, 3 and entered Jefferson Medical College in 1911. 4 Following medical school, he began working as a general practitioner in DuBois, Pennsylvania, but after just one year, his career was interrupted by the U.S. declaration of war with Germany on April 6, 1917.

WITH THE BRITISH ARMY

On August 8, 1917, at the age of 31, Harry Fulton enlisted in the Officers Reserve Corps of the U.S. Army. After beginning active duty as a first lieutenant later that month, 2,4 he sailed for England from Hoboken, New Jersey, on October 3 aboard the Royal Mail Ship Aurania. (This British ocean liner was torpedoed the following February by a German submarine, with the loss of nine crew members. 5 After arriving in England, he was temporarily stationed on England’s east coast, where many military camps were then situated, before being assigned for several months to the British Expeditionary Force in France.

On February 25, 1918, in a long letter home to E.W. “Chess” Keyzer (Text Box 1), he described his circumstances with the 131 st Field Ambulance * of the Royal Army Medical Corps in France. 4 Authorities did not permit soldiers’ letters to indicate their location, but the unit’s records 6 indicate it was then at the aptly named Waterlands Camp in the north of France, about 15 miles south of the much fought-over Belgian city of Ypres. The 131 st Field Ambulance 7 served the 38th Welsh Division, which had received its baptism of fire at the Battle of the Somme in July 1916, when it lost nearly 4,000 men. 5,8

Harry Fulton was engaged in the Battle of the Lys 1 (also known as the Fourth Battle of Ypres). Fought from April 7-29, 1918, it was part of the German Spring Offensive (Operation Georgette), intended to capture Ypres and force the British troops back to the seaports and out of the war. The offensive did not achieve its objectives, and it ended on April 29 with about 82,000 killed or wounded on each side. 5

WITH EVACUATION HOSPITAL NO. 7 AT COULOMMIERS

In July 1918, Harry Fulton was detailed to the U.S. Army Medical Department’s Casual Operating Team No. 514, which reported for service at Evacuation Hospital No. 7. This unit occupied the Château de Montanglaust in Coulommiers, 9 some 40 miles east of Paris and 26 miles from the battlefront at Château-Thierry. 10 (Fig. 1)

Fig. 1. View of the Château de Montanglaust in Coulommiers, which was occupied by Evacuation Hospital No. 7 on June 12, 1918. Harry Fulton arrived here with Casual Operating Team No. 514 on July 16, 1918.

Fig. 1. View of the Château de Montanglaust in Coulommiers, which was occupied by Evacuation Hospital No. 7 on June 12, 1918. Harry Fulton arrived here with Casual Operating Team No. 514 on July 16, 1918.

(Source: https://worldwar1letters.files.

wordpress.com/201/06/chateaumontanglaust1.jpg).

Soldiers wounded at the front line were brought to an Evacuation Hospital, where they received initial surgical care and (ideally) could be stabilized for several days and begin recovery. From there, they were taken by hospital trains to base hospitals, where they could receive more complicated procedures and recuperate. 11

When Harry Fulton arrived, the hospital was receiving wounded from the the Second Battle of the Marne, the last major German offensive on the Western Front, fought from July 15 to August 6. 10 German bombs had been dropped on the hospital the night before, but missed their target and only damaged the Château’s window glass. The entry in the hospital’s logbook for July 17 reads:

The earth fairly quakes today, for the steady roaring drum fire seems to vibrate the country for miles around. Patients are coming rapidly and trucks are lined up and down the road for almost half a mile. The hospital is full of patients and many of the slightly wounded and gas cases are lying on litters about the bank, under the trees. Ambulances are taking the patients away to the hospital trains and others are bringing them in from the front…

Truckloads and ambulance-loads of patients continue to come today, and the men are still working, although many of them have not slept for seventy-two hours. Another bunch of nurses and enlisted men arrived last night, and there is plenty of work for all. Trains are ordered, one after another, to carry the patients to the rear and make room for more, for there are prospects of many more coming. Seven trains, carrying about 2640 patients were sent out from this hospital from noon yesterday to noon today...Six more surgical teams were added today [presumably including Harry Fulton’s Casual Operating Team No. 514], which will give those who have been on duty a rest which they greatly need. We have eighteen operating tables going day and night.10

Their staggering workload is indicated by the fact that, in the six weeks after June 13, 1918, Evacuation Hospital No. 7 received and evacuated 27,000 cases. 9

WITH EVACUATION HOSPITAL NO. 7 AT SOUILLY

On August 19, 1918, Evacuation Hospital No. 7 departed by train for Neufchâteau, some 150 miles to the east. Arriving in the region in the early morning of August 21, officers and nurses went on to nearby Bazoilles-sur-Meuse, where Base Hospital No. 18 was in operation. (Dr. Fulton’s name is mentioned on its list of officers. 12) They soon received new orders, and on August 24 the unit travelled to Souilly, some 65 miles to the north and 11 miles from the much fought-over city of Verdun.

At Souilly, Evacuation Hospital No. 7 operated together with Evacuation Hospital No. 6 in a former French hospital, which was transferred with practically all its equipment (Fig. 2). A railroad with receiving and dispatching platforms lay in front of the two hospitals (Figs. 3 and 4). Evacuation Hospitals Nos. 6 and 7 had nominal capacities of 1,000 and 1,200 beds respectively, but records indicate that the maximum number of patients held at one time in the combined units exceeded 3,800. 9,10

Fig. 2. View towards Evacuation Hospitals Nos. 6 and 7 at Souilly. Harry Fulton presumably arrived here on August 25, 1918. (Source: http://resource.nlm.nih.gov/101399957).

Fig. 2. View towards Evacuation Hospitals Nos. 6 and 7 at Souilly. Harry Fulton presumably arrived here on August 25, 1918. (Source: http://resource.nlm.nih.gov/101399957).

Fig. 3. View of the receiving and dispatching platform in front of Evacuation Hospitals Nos. 6 and 7 at Souilly. The soldiers walking towards the photographer are German prisoners of war. (Source: http://resource.nlm.nih.gov/101399944).

Fig. 4. Current day view of the fields in Souilly where Evacuation Hospitals Nos. 6 and 7 were located in 1918. The concrete structure is presumably the remnant of the receiving and dispatching platform. (Photo taken by author on May 7, 2016.)

The entry in the logbook of Evacuation Hospital No. 7 for August 25 (before the onslaught of casualties) reads:

The camp where we are located is a French hospital and has never been in the hands of the Americans before. The wards are all good buildings and the men all have barracks to live in. It is, by far, the best place we have had in France. The French have made the place very beautiful with flowers and have kept the grounds in excellent condition. Evacuation Hospital No. 6 is here and will operate a hospital here also, the camp will be divided and No. 7 will take the north end and No. 6 the south, both operating independently.9

Evacuation Hospital No. 7 started operating as a hospital again on August 28, but at first the cases were mainly personnel with influenza/Spanish flu (see below). The Battle of St. Mihiel, the only offensive launched solely by the U.S. Army in WWI,5 commenced on September 12 and ended September 14.9,10 The hospital’s logbook entry for September 12 reads:

The big drive is on. Early this morning the big guns began talking to Heinie and Fritz … The barrage lasted for several hours and it is reported that our troops are attacking on all sides of the St. Mihiel salient. The hospital is in readiness for the wounded and the first of them are expected to arrive some time during the night.10

THE NOTEBOOK OF HARRY FULTON

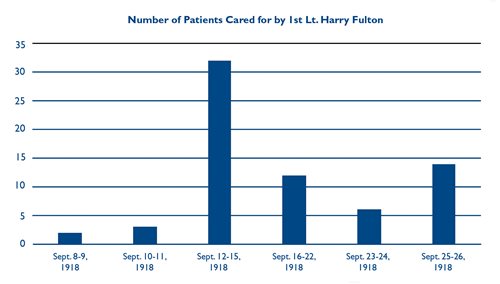

On September 8, shortly before the Battle of St. Mihiel, Harry Fulton began writing down names and notes about his patients at Evacuation Hospital No. 7 in a little booklet (6.6" x 4.3"), which ultimately listed 69 named patients. The first entry is dated Sept. 8, 1918, and the last two are on Sept. 25 and 26. (Fig. 5) During this interval the U.S. Army engaged in the Battle of St. Mihiel, and the first phase of the Meuse-Argonne Offensive (September 26 – October 3, 1918).5

Fig. 5. Bar graph showing the number of patients cared for by Harry Fulton at Evacuation Hospital No. 7 in Souilly per time period based on dates mentioned in his notebook. From September 12 to 15, 1918, 32 patients were cared for, most of which were presumably casualties of the Battle of St. Mihiel (September 12-14, 1918).

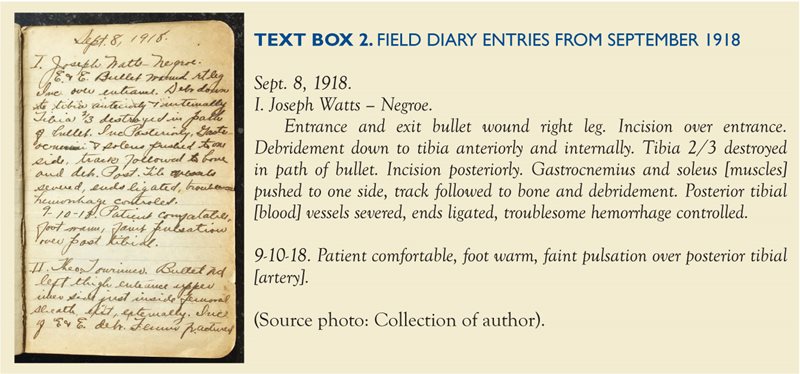

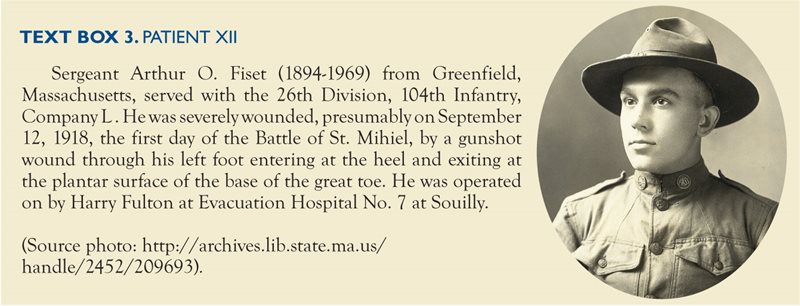

The description of the first patient takes up two-thirds of one page, and also mentions follow-up observations made the day after surgery (Text Box 2), but the notes get progressively shorter to the point that some patients are described in one line only. While most patients listed in the notebook received treatment because of wounds or injuries, three patients were operated on for appendicitis. (Although the handwriting is often illegible, it was possible to identify several of the patients using Google’s search engine, online digitized archives, and digitized newspapers with casualty lists (Text Box 3).)

WITH EVACUATION HOSPITAL NO. 7 AT ST. JUVIN

The last date mentioned in the notebook is Sept. 26, 1918, the day the Meuse-Argonne Offensive was launched. Involving 1.2 million U.S. troops, it remains the largest frontline commitment in American military history, and is considered “America’s deadliest battle,” because the often-inexperienced American soldiers sustained over 26,000 killed and over 95,000 wounded. The Meuse-Argonne Offensive coincided with the so-called “second wave” of Spanish flu,** which ran its deadly course on the Western Front for about eight weeks, from mid-September to mid-November 1918. One in four American soldiers caught the flu.13 It can be imagined that Evacuation Hospital No. 7 was flooded with patients from September 26 onwards, leaving Harry Fulton no time to keep notes. Indeed, the entry in the hospital’s logbook for October 1 says that 1,053 patients were admitted in 24 hours, many with pneumonia, which was responsible for 60-70% of deaths.10 Though the logbook doesn’t mention it, the hospital staff was doubtless depleted by the flu, as was documented for other medical units.

On November 7, the hospital moved to St. Juvin, some 30 miles northeast of Souilly. The town was in ruins, without any building that could serve a useful purpose. The hospital settled around the remnants of the railway station, and opened on November 10, one day before the Armistice was signed on November 11, 1918. Three days later, on November 14, the hospital stopped taking patients and evacuated all except a few serious cases.10

WITH CAMP HOSPITAL NO. 70 AT ST. FLORENT-SUR-CHER

On November 23, 1918, Casual Operating Team No. 514 was relieved from duty with Evacuation Hospital No. 7.9 Harry Fulton subsequently served as a casual officer, which indicates that he was not assigned to a specific unit,2 but a “Harry C. Fulton, M. C.” is mentioned as a member of the staff of Camp Hospital No. 70. Established near the end of the war in September 1918, and located in an old factory building of 300-bed capacity in St. Florent-sur-Cher in central France, it was operated by Field Hospital No. 156 for the medical care of the 39th Infantry Division. On January 13, 1919, two months after the Armistice, Field Hospital No. 156 was relieved from duty at Camp Hospital No. 70 and was replaced by a detachment of casuals, which probably included Harry Fulton. When Camp Hospital No. 70 ceased operating at the end of January, all patients of were evacuated to a nearby camp hospital, and all personnel were reassigned to other stations.14

Harry Fulton was promoted to captain in February, 1919, and on May 11 he sailed back to the U.S. from St. Nazaire, France, on board the USS Manchuria. Arriving in Hoboken, New Jersey on May 22, he was honorably discharged from the U.S. Army on May 26 at Camp Dix, New Jersey.2

MEDICAL CAREER AND LIFE AFTER WORLD WAR I

After the war, Harry Fulton returned to DuBois, Pennsylvania, a city of just 13,000 people then (and fewer today), where he practiced until 1927 and became chief of a genitourinary clinic. He then obtained two years of post-graduate training in ophthalmology at the University of Pennsylvania. After graduating in 1929, he moved to Lancaster as the first full-time board-certified ophthalmologist, with an office at 339 North Duke Street. He retired in January 1974 at the age of 88, after practicing medicine for 58 years (Fig. 6).1,3,4,15 John Bowman, a Lancaster retired ophthalmologist, remembers Harry Fulton as informal, cordial, and a fine gentleman for whom he had the utmost professional respect. Dr. Barton Halpern, also a retired Lancaster ophthalmologist and board member of the Edward Hand Medical Heritage Foundation, currently owns the surgical kit of Harry Fulton (Fig. 7).15

Fig. 6. Dr. Harry Fulton in 1974, the year he retired as an ophthalmologist after practicing medicine for 58 years. (Source: Intelligencer Journal. June 6, 1989: B-3).

Fig. 7. The named surgical kit of Harry Fulton. The inset shows the nameplate with the name H.C. Fulton attached to the lid of the kit. (Source: Collection of Barton Halpern, M.D.)

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The author thanks Jean Korten, Bernadine Lennon, Anneliek Holland, and Drs. Paul Ripple, John Bowman and Barton Halpern for their help in preparing the manuscript.

* Field Ambulances were mobile front line medical units consisting of more than one vehicle. With a capacity of 150 wounded, many would often be overwhelmed by the sheer number of battle casualties. An infantry division had three Field Ambulances, each responsible for the casualties of one of the brigades in the division.

** We now know this epidemic was caused by a mutated avian flu virus that made the trans-species leap to humans, a possibility we are again wary of in the 21st century. Also known as “La Grippe,” it is estimated that the Spanish flu killed from 20 to 100 million people worldwide. Wherever it became prevalent, hospitals were usually full despite discouraging the admission of contagious patients. Worse, their own staffs were depleted as doctors and nurses succumbed.

REFERENCES

1. Ripple P, Bowman J. A history of ophthalmology in Lancaster County. J Lanc Gen Hosp. 2012; 7 (2):51–55.

2. https://www.ancestry.com

3. Dr. Harry Fulton, 103, ophthalmologist. Intelligencer Journal. 1989 June 6: B-3.

4. https://www.newspapers.com.

5. https://en.wikipedia.org.

6. http://www.ciaofamiglia.com/jcsproule/WWI_PDFS/Jimmy_Sproule_WWI.htm

7. http://www.ciaofamiglia.com/jcsproule/WWI_PDFS/38th_Div_&_131_Fld_Amb_in_WW1.pdf.

8. http://www.longlongtrail.co.uk/army/order-of-battle-of-divisions/ 38th-welsh-division/.

9. Lynch C, Ford JH, Weed FW. The Medical Department of the United States Army in the World War, Volume VIII: Field Operations. Government Printing Office, Washington, DC, 1925.

10. The Log Book of Evacuation Hospital Number Seven A.E.F.: November 25, 1917: May 1, 1919. N.p., n.d.

11. Marble S. Skilled and Resolute: A History of the 12th Evacuation Hospital and the 212th MASH: 1917-2006. Borden Institute, Fort Sam Houston, Texas, 2013.

12. History of Base Hospital No. 18: American Expeditionary Forces (Johns Hopkins Unit). Base Hospital 18 Association, Baltimore, Maryland, 1919.

13. Wever PC, van Bergen L. Death from 1918 pandemic influenza during the First World War: a perspective from personal and anecdotal evidence. Influenza and Other Respiratory Viruses 2014;8:538–546.

14. Ford JH. The Medical Department of the United States Army in the World War, Volume II: Administration American Expeditionary Forces. Government Printing Office, Washington, DC, 1927.

15. Email messages from Drs. John Bowman and Barton Halpern to author.

16. https://www.findagrave.com/cgi-bin/fg.cgi?page=gr&GRid=100326132.

|

|