Fall 2015 - Vol. 10, No. 3

Physican-Assisted Dying

Additional Thoughts

Lawrence I. Bonchek, M.D., F.A.C.S., F.A.C.C.

Editor-in-Chief

Death! No topic is more important, and most people try to avoid thinking about it, but as physicians we deal with it regularly. When it threatens our patients they seek our help, but fulfilling our responsibility to them is challenging, perhaps because doing so forces us to confront our own mortality.

So it’s understandable that my recent editorial on Physician Assisted Dying (PAD) generated more responses than any previous column.1 In the current column I’ll discuss related articles and opinions from various sources which have appeared with increasing frequency since Brittany Maynard, a 29-year-old Californian with a terminal brain tumor, very publicly moved to Oregon last fall so she could voluntarily end her life legally. Another reason for the media buzz is that legislation to legalize PAD has been introduced in several states. (Oregon legalized PAD in 1997; Washington and Vermont did so subsequently. Courts in Montana and New Mexico achieved the same result by refusing to prosecute physicians who provided aid in dying. Pennsylvania [House Bill 943], California, and New York, among others, are considering such legislation.)

OTHER VOICES

I personally believe that physicians should be allowed to help certain terminally ill patients end their lives if they meet a number of stringent criteria, but I understand and respect those who hold opposing views. My previous editorial cited the major concerns about PAD: that it might be offered disproportionately to the poor, the elderly, the uninsured, the uneducated, the disabled, or the mentally incompetent; and that some patients might even feel they owe it to their overburdened families to end their struggle.

In the spring issue of Lancaster Physician,2 Drs. Tom Gates and Tom Miller offered some thoughts and guidance about Physician-Assisted Suicide* and added two more concerns: insurance companies might see this as an opportunity to cut costs and pressure patients to terminate their lives prematurely; and acceptance of the concept could gradually lead to its being offered to patients who are suffering but are not terminally ill.

In fact, all such fears have proven groundless. Ever since Oregon made PAD legal in 1997, the Oregon Health Authority’s Division of Public Health has kept detailed records of how and why the law is used, which it releases every year.3 During these 17 years, 859 Oregonians died from taking the prescribed drugs, an average of 50 per year. They constitute less than 0.2% of the nearly 530,000 Oregonians who died during that period. About one third of patients who obtained the drugs never used them, suggesting that they were satisfied to have gotten control over the manner and timing of their deaths.

Most patients seeking PAD are white, are receiving hospice care, and have a cancer diagnosis. They are disproportionately well-educated and well off, and nearly all have health insurance. They are the type of people who particularly value control and independence; 91% cited fear of loss of autonomy as the reason they sought PAD.4 There has been no suggestion of coercion of the weak, disabled, minorities, or disadvantaged.

That Oregon’s law has remained popular and functional for 17 years does not mean, however, that it is universally acclaimed. The Wall St. Journal recently published an op-ed piece by Dr. William Toffler of Physicians for Compassionate Care (PCC), an Oregon organization whose board consists predominantly of several faculty members at the Oregon Health Sciences University opposed to providing assistance with dying.5 In his WSJ article, and in a similar article on the website of PCC,6 Dr. Toffler argues that most patients who seek information about PAD do so for psychological or social reasons. Intractable pain is rarely the cause, and more likely reflects inadequate medical management. He concludes that “assisted suicide has been detrimental to patients, degraded the quality of medical care, and compromised the integrity of the medical profession,” and he contends that it has been “totally unnecessary in Oregon.” It must be pointed out, however, that he cites only his anecdotal experience as a family physician, and he presents no actual data.

The WSJ must have received a flood of letters from Oregonians who differed with Dr. Toffler, judging by the unusually large number they published.7

In one letter a woman from Portland, Ore., reminded us that cancer isn’t the only cause of intolerable suffering. Her mother had end-stage emphysema and “the last four months of her life were miserable. She couldn’t breathe, could barely walk and was skin and bones when she finally died. All her physicians … carefully continued to evaluate her mental health up to the minute she took the drug that let her die in peace. This was purely her choice. No one persuaded her to do this.”

A writer from Roseburg, Ore., said “We Oregonians take great comfort knowing that should we become terminally ill we will be legally entitled to die without enduring months or years of misery. I prefer to live in a state where my doctor and I can make this decision, rather than society at large imposing its collective will on my right to die with dignity.” A third writer from Beaverton, Ore., said: “As a patient, I am not worried about “death doctors.” I am worried about doctors who use any treatment available to prolong life without having a matter-of-fact discussion with the patient about what the quality of that prolonged life will be. After seeing what my friends had to endure in their final days, I thank God I live in a state that gives me the choice to leave on my terms.”

Since Toffler’s sincerely held opinions were not supported by data, the recorded experience of the Death with Dignity program of the Seattle Cancer Care Alliance, which was reported in the New England Journal of Medicine,4 is instructive.

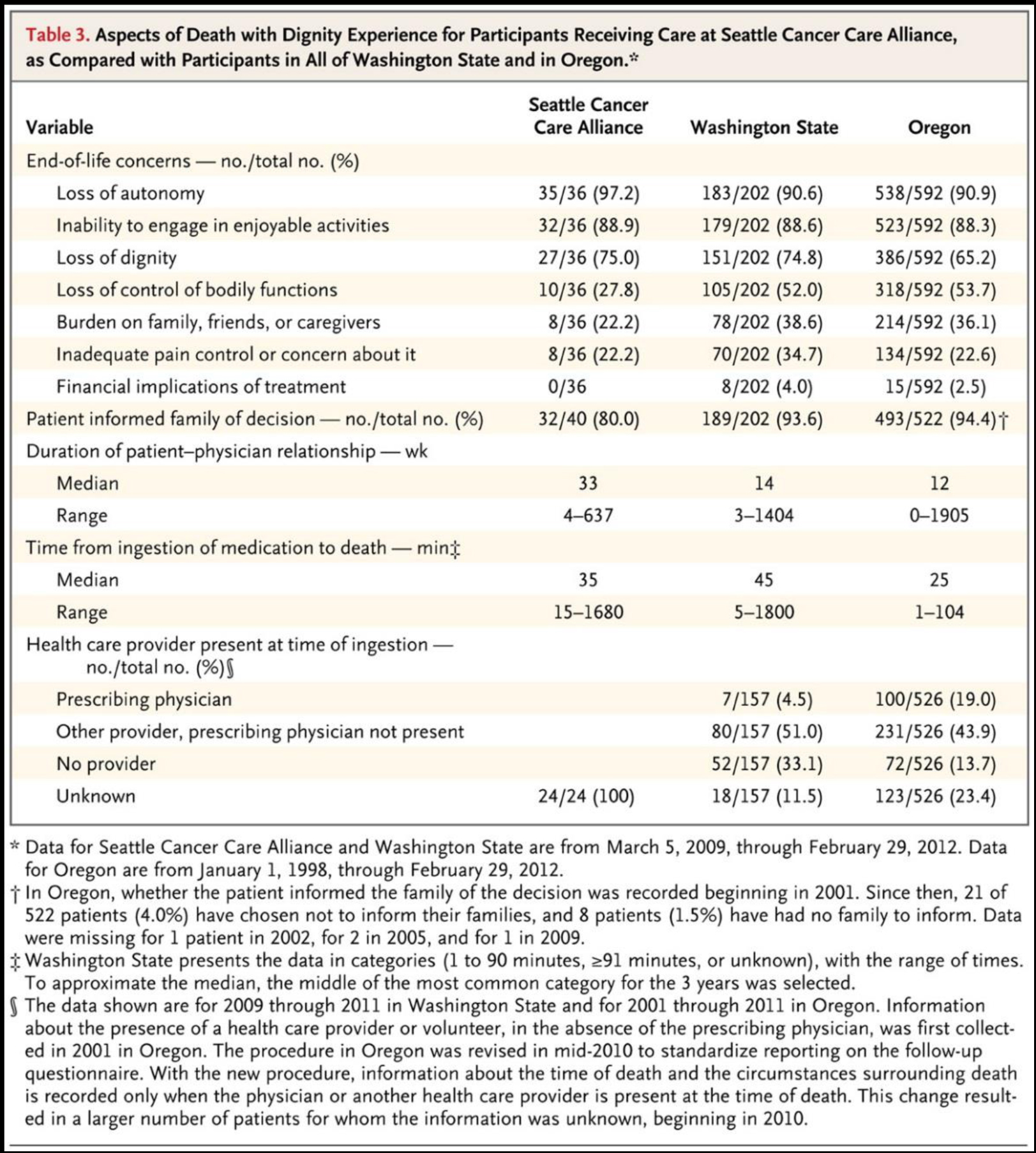

The most common reasons given by patients for wanting to participate in Death with Dignity were loss of autonomy (97.2%), inability to engage in enjoyable activities (88.9%), and loss of dignity (75.0%). Eight of 36 participants (22.2%) reported uncontrolled pain or concerns of future pain. None of the patients who inquired about Death with Dignity and were found to have either current or previous depression or decisional incapacity elected to move forward with the process. And from the reverse side, no patients who pursued Death with Dignity were deemed to require mental health evaluation for depression or decisional incapacity. (Table 3 from this report is reproduced with this article on our website.8

CULTURAL INFLUENCES

Cultural views of death have a powerful influence on attitudes toward PAD, so it is instructive to consider the attitude of Jainism.** The NY Times described the death of one of its followers in an article in August, 2015:9

“All week, people streamed in and out of the handsome bungalow where the Lodha family lives, eager to witness for themselves the amazing event that was occurring there.

“On a bed in a corner of a large sitting room, surrounded by a crowd of reverent visitors, the family’s 92-year-old patriarch, Manikchand Lodha, was fasting to death. It was the culmination of an act of santhara, a voluntary, systematic starvation ritual undertaken every year by several hundred members of the austere, ancient Jain religion.

“Mr. Lodha had begun the process some three years earlier, after a fall left him bedridden. First he renounced pleasures like tea and tobacco. Then things he loved, like television. He gave up medicine, even refusing an air mattress to ease his bedsores. On Aug. 10, he took the ancient vow and gave up food and water.”

It should be understood that Mr. Lodha was hardly an ascetic, and was born into a prominent family that runs a group of electronics and technology companies. But after he became bedridden and slowly abandoned one thing after another, his son, Sumitlal, said: “He was leaving. I was observing it very minutely because I was the caretaker, how he was making his circle smaller and smaller.” When the end seemed imminent, an invitation circulated on WhatsApp and the house filled with visitors and celebrants. “His face was shining like the sun,” said a relative of Mr. Lodha’s wife, who said this was the 40th santhara he had witnessed.

“When Mr. Lodha died Aug. 16, the house was festooned with orange-and-white bunting. Visitors were offered bowls of sweets bathed in syrup. ‘Look at us — do we look like we are in mourning?’ said Sunita, Mr. Lodha’s daughter-in-law. ‘We are celebrating, because one of our family members has achieved something great. We were able to know him. That was our good fortune. Santhara is something that came to him. It does not come to everyone. He must have done something good that he got such a death’”

Ironically, a lawsuit has been working its way through the Indian courts which charges that the Jain’s practice of santhara violates Indian laws against suicide!

It struck me that in Western culture, Tolstoy’s short story The Death of Ivan Ilych contains a similar description of joy and eager anticipation in the final stages just before the death of its eponymic protagonist. Ilych, who has lived a superficial and self-indulgent life, finally achieves an end to his mental and physical suffering when he accepts the inevitability of death as a part of life.

As I noted in my last editorial, suicide prompted by illness is accomplished frequently in the U.S. with or without the government’s approval. There are many ways of ending one’s life voluntarily here: fasting is commonly used, though it is hardly celebrated in the manner of the Jains (perhaps it should be); dialysis patients simply stop dialysis; and when all else fails, guns are ubiquitous.

PUBLIC ATTITUDES

The widely respected Franklin & Marshall poll of registered voters in Pennsylvania recently asked several questions about attitudes toward end-of-life issues.

1. The Medicare program recently announced that it will begin paying doctors to have discussions about end-of-life care with their patients. Which of these statements most closely reflects your beliefs about end-of-life care?

72% - It is more important to enhance the quality of life for seriously ill patients, even if it means a shorter life.

21% - It is more important to extend the life of seriously ill patients through every medical intervention possible.

7% - Don’t know

2. It is just as important for patients and their families to understand end-of-life care options as it is to understand their treatment options.

83% -Strongly Agree

11% - Somewhat Agree

2% - Somewhat Disagree

2% - Strongly Disagree

2% - Don’t know

3. Some states allow doctors to help their terminally ill patients end their lives. Do you think that doctors in Pennsylvania should or should not be allowed to help terminally ill patients end their lives?

57% - Should be allowed

35% - Should not be allowed

8% - Don’t know

The overall differences are significant as are several differences when responses are broken down by various demographic characteristics such as age, gender, political affiliation and self-described ideology etc.. (Space does not permit us to publish them here, but they will accompany this article on our website.) As noted, the public sampled in this poll strongly supports legalizing PAD by a margin of 57%-35%.

FINAL THOUGHTS

The aforementioned article by Drs. Gates and Miller2 also raised some interesting cultural questions. In their words, “The issue of PAD raises profound questions about our culture’s ability to deal with suffering. Suffering would seem to be an inevitable part of life, and the notion that it is best dealt with by a pill seems very impoverished...we have come to expect that all pain is curable, even the pain of death. The fact that what is inevitable has become so intolerable that we look beyond our traditional sources of strength in family, community and faith to instead “manage” death with a pill raises the question: “What kind of people have we become?”

I would suggest that the sentiments expressed by Drs. Gates and Miller reflect our universal admiration for endurance. We make heroes of those who withstand privation and suffering as prisoners of war, captured spies, shipwrecked sailors, or polar explorers (Shackleton named his ship the Endurance!). Their fortitude ennobles all humans because we are proud of what we humans can achieve when pushed to our limits. But though we admire those who suffer heroically after they (usually voluntarily) are put in harm’s way, few of us anticipate or desire such experiences.

Death, however, comes to us all, and I do not think that an effort to minimize suffering in the final stages of life degrades us as physicians or as a society. To the contrary, it reveals the compassionate side of our nature and elevates us as physicians. Since we go to elaborate extremes to alleviate suffering among the living, why would we not do the same for the dying when they ask for our help?

IN THIS ISSUE

This issue features an authoritative and comprehensive article by Drs. Galindo and Furth on non-alcoholic liver disease that reviews its terminology, natural history, prevalence, diagnosis, and laboratory and histological findings.

Dr. Walid Hesham provides a fascinating review of enhanced recovery after colorectal surgery. New methods of management shorten recovery and lower costs by dramatically simplifying preoperative preparation of the bowel, and accelerating postoperative feeding.

An article from the Lipid Task Force provides guidelines to the management of dyslipidemias, an area that has become increasingly confusing due to uncertainty about ideal cholesterol levels.

Drs. Bansal and Leslie, with Lisa Estrella, explain that many patients with cardiac pacemakers can undergo MRI examinations, something that was considered contraindicated until now.

Jessica Yoder and Tomomi Horning from our Pennsylvania College of Health Sciences surveyed blood donors to provide insight into the factors that motivate donors to first become interested in donating, and then to continue as regular donors.

And as always, Dr. Alan Peterson provides his regular column on Choosing Wisely and Top Tips.

A FOND FAREWELL

After six outstanding years as our indispensable Managing Editor, Alrica Goldstein is leaving us to fulfill a dream of taking an extended trip around the globe with her husband and two children while the children are still young enough to be home-schooled along the way. At our 10th Anniversary Dinner on June 2 in Lancaster, which was attended by members of our Editorial Board, as well as President and CEO Tom Beeman, we took the opportunity to introduce our new Managing Editor Jean Korten and to wish Alrica a fond farewell and a marvelously fulfilling trip.

Photo taken at thd 10th Anniversary Dinner of LGH. Pictured, from left, are Dr. Laurence E. Carroll,

Dr. Alan S. Peterson, Dr. Lee M. Duke II, Christopher M. O'Connor, Esq., Dr. Lawrence I. Bonchek,

Dr. Joseph M. Kontra, Alrica Goldstein, Dr. Tom Beeman, and Dr. Leigh S. Shuman.

REFERENCES

1.Bonchek, L.I. Physician-Assisted Dying. J Lanc Gen Hosp. 2015; 10 (2):33-36. http://jlgh.org/Past-Issues/Volume-10---Issue-2/Editor-s-Desk---Physician-Assisted-Dying.aspx

2.http://issuu.com/nhgi/docs/lp_spring15_lr/l

3.http://public.health.oregon.gov/ProviderPartnerResources/EvaluationResearch/DeathwithDignityAct/Documents/year17.pdf

4.Loggers, ET, Starks, H, Shannon-Dudley, M et al. Implementing a Death with Dignity Program at a Comprehensive Cancer Center. N Engl J Med 2013; 368:1417-1424 DOI: 10.1056/NEJMsa1213398***

5.Toffler, WL. A Doctor-Assisted Disaster for Medicine. Wall St. Journal. Aug. 17, 2015

6.www.pccef.org

7.http://www.wsj.com/articles/many-near-death-welcome-the-choice -of-a-swift-exit-1440540168

8.www.jlgh.org

9.http://www.nytimes.com/2015/08/25/world/asia/sects-death-ritual-raises-constitutional-conflict-in-india.html?_r=0

*I prefer the term “Physician-Assisted Dying” because the Gallup Poll found that public approval of the concept rises from 51% to 70% when that wording is used. That result is not surprising, since dying is part of life, but suicide is not.

**Jainism is a non-theistic religion of the Indian subcontinent that grew out of Hinduism in the 6th Century, about the same time as Buddhism, with which it has many similarities. It emphasizes the perfectibility of human nature and liberation of the soul through conquest of worldly passions like greed, hatred, pride, anger, and desire (“Jina” means conqueror). It emphasizes non-violence toward all living things, and teaches the immortality and transmigration of the soul, which profoundly influences the approach to death. There are currently about 6 million followers throughout India, concentrated in certain states.

Source: New England Journal of Medicine 2013 (Loggers ET et al. N Engl J Med 2013; 368:1417-1424)